Plant Hardiness Zones and Garden Microclimates

This post may contain affiliate links. Read my full disclosure here.

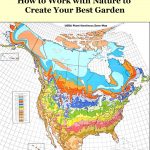

When you’re planning a garden or other plantings, you need to know both your Plant Hardiness Zone and your microclimate. Per the USDA, the zone maps “gardeners and growers can determine which plants are most likely to thrive at a location”.

The USDA Plant Hardiness Zones and Microclimate

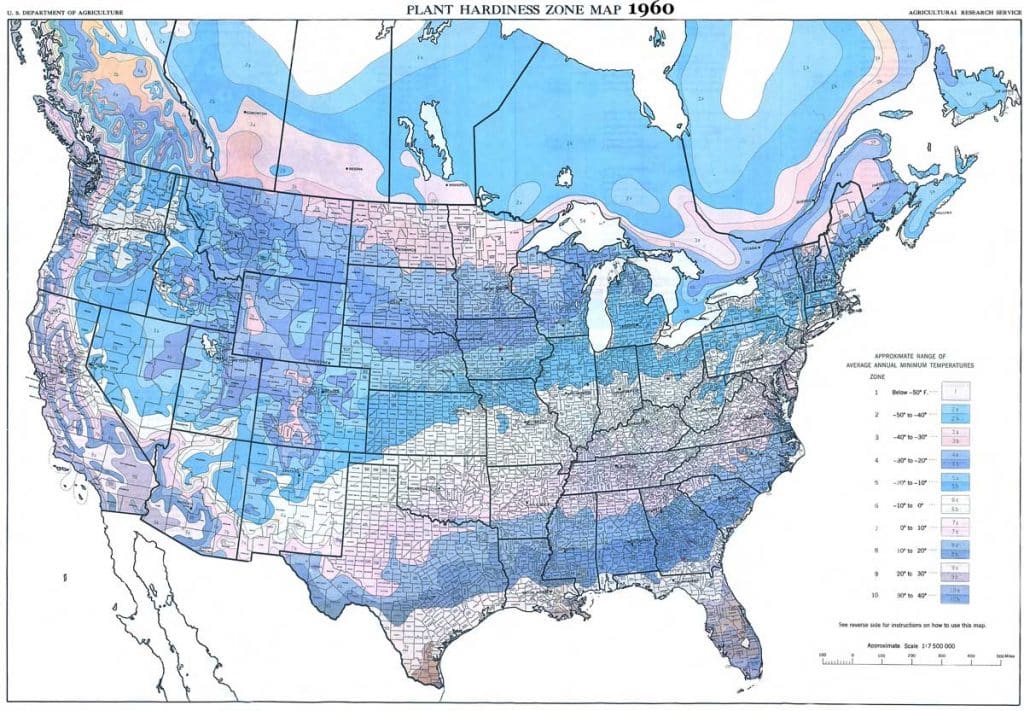

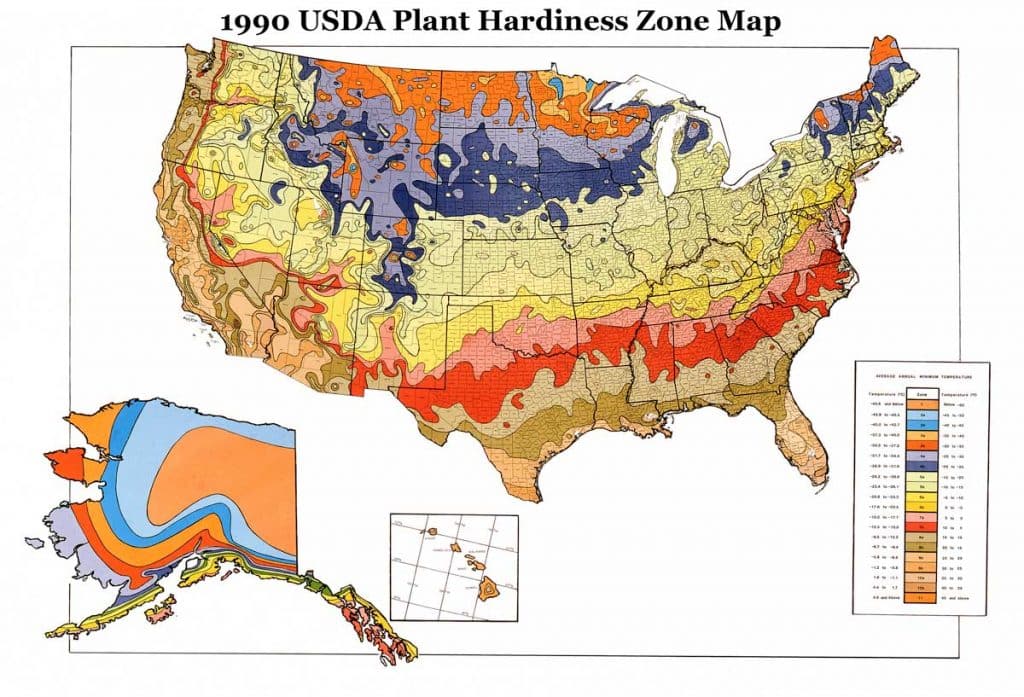

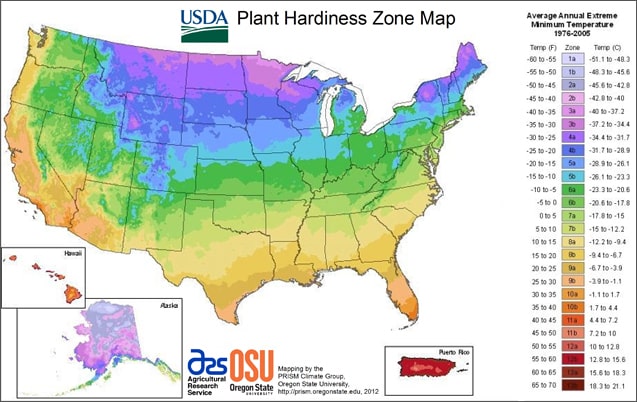

The map divides North America into 11 separate zones, plus a and b sub-zones. The map is based on the average annual minimum winter temperature, divided into 10-degree F zones. The USDA plant hardiness zones are a good starting point, but they don’t give the full picture.

Each location is also influenced by local elements, such as water and buildings, to create a microclimate. To be successful, you need to know your zone and you need to know your local microclimate.

What is a microclimate?

A microclimate is the climate of a very small or restricted area, especially when this differs from the climate of the surrounding area. We’ll use the microclimate in our 10 acre permaculture project later in this article as an example. A microclimate can allow you to plant trees, vegetables or fruits that would otherwise die, or at least be stunted.

What are three things that can create microclimates?

Water, mass and windblocks are three things that can create micro-climates. Here are a list of other examples:

- A pond or a rock pile can store heat and release it when the air temperature gets cold.

- Valleys, swales and berms can reduce direct wind and trap moisture.

- Parking lots can store heat in the day and release it at night. A treeline can reduce wind and increase moisture slightly.

- Large buildings can also function like a treeline, reducing wind and storing and releasing heat.

- A city creates a large microclimate. In many cases a full zone or more warmer than the forest and farmland around it.

A microclimate can be produced by many things. With the right modifications, you can change your plant hardiness zone and microclimate, like Sepp Holzer growing citrus in the Alps.

What is it about Cities that make them Microclimates?

When we lived in the suburbs the weather was a few degrees warmer. Cities and suburbs create a microclimate. The buildings stop wind, the asphalt holds heat, as do the buildings. It creates weather that is more moderate, than even 5 miles away in the country.

Larger cities can even impact rain, wind and snow by creating micro updrafts and downdrafts. Most city plantings will be 1/2 to one full zone warmer than their map location, but they may also suffer from too much heat and not enough water. Just like a rural location, track your temperatures, rain and wind.

Watch for trends more than averages. It’s the extremes that cause trouble. One month of heavy rain and one month of no rain equals two months of “average rain”.

Why can bodies of water create microclimates?

Water holds heat, and also absorbs heat. It can reduce highs and lows evening temperatures, and increasing local humidity. Larger bodies of water do it best, but smaller water bodies, even a small pond can impact your microclimate.

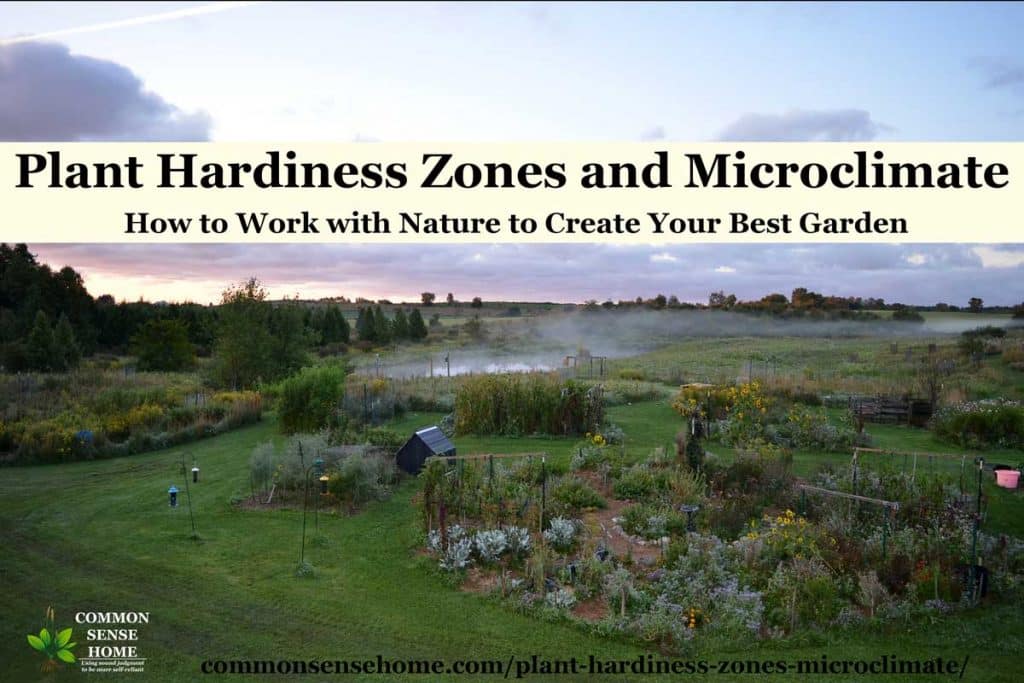

Our 1/2 acre pond creates a cool breeze on a warm day, and radiates stored heat on a cold night. You can see the fog rolling off the pond in the background below on a chilly fall morning.

Do the USDA maps matter?

Yes and No. The USDA maps have been updated twice. The original map is 1960, the 2nd is 1990 and the newest is 2012. Here in Wisconsin, we live in an area that was solidly in Zone 4 in 1960.

The latest zone maps show us in Zone 5. We tried planting a couple Zone 5 magnolias, and they died. Many of the temperature readings used to create the USDA hardiness zone maps have been affected by urban sprawl (showing higher microclimate temps and shifting the zones north). Your microclimate may or may not match your current hardiness zone.

The maps don’t tell us how frequently the temperature was below zero, and for how long. It just tells us the average in sets of 10 degree areas.

In reality, neither of those numbers matter because they only give you a starting point. The maps don’t tell the whole story. What really matters is the plant hardiness zone and microclimate combined.

Cold temps for a single night is not the same as weeks of the same temperature, and a combination of wind, cold and humidity impacts various plants differently.

A plant that experiences zero degrees could be damaged and recover if temps come back up, but will die with extended periods of cold. One night of cold and the plant survives but a week of cold and it dies. Temperature swings are also very tough on most plants.

Friends of ours in Canada had unusually deep snow during the winter of 2017-2018, and lost almost all of the fruit trees they can carefully nurtured for years. The deep snow allowed the voles to girdle the trees at heights at above five feet. Extremes matter.

Cold Summers

Cold summers can damage trees and plants. A lack of heat reduces sugar production and reduces the ability of the plant to survive winter cold. So again the summer “average” might be meet the “zone requirement”, but the plants could still die because of the actual weather you experience.

What are the best plants for my hardiness zone?

Pay attention to what is actually growing. Talk to farmers, visit orchards and walk around local nurseries. Note we said LOCAL nurseries, not nurseries where trees are trucked in at Home Depot, Lowes or your local supermarket.

The “big box store” plants may look happy but might die quickly in your garden or yard. The seasonal nurseries may be beautiful and tempting, but the plants, trees and shrubs may be from a few zones warmer or colder than your location.

Track what grows well over several seasons, without excess care. If you have the time and energy to pamper record breaking produce, that’s great, but for those who want a low input garden, your easiest path to success is to start with what generally works well in your area. I don’t attempt to grow pineapples, but homegrown melons and tomatoes are worth a little extra effort for us.

One method we came across is called Simple Total Utter Neglect (STUN), which is practiced by Mark Shepard of Restoration Agriculture. Mark plants hundreds of trees, and then plants more of the ones that do the best with the least care.

We don’t really follow STUN. We protect trees from the deer and do some pruning and fertilizing, but we don’t excessively pamper the trees and shrubs. We improve the soil, adding mycorrhizal fungi and compost, and water when needed.

Ways to Change Your Microclimate

Even if you don’t have ideal growing conditions, there are many options for improvement.

Make your own Microclimate

If you need a modest amount of growing space in a protected microclimate consider a greenhouse, coldframe or hoophouse. For more information see:

Would you like to save this?

- The Practical Greenhouse Guide – DIY Greenhouses Done Right

- Protecting Plants from Frost – 12 Ways to Beat the Cold Weather

- The Forest Garden Greenhouse: Creating an Indoor Permaculture Oasis

To create a microclimate that effects a larger area of your property, try some of the options below.

Windbreaks

Use buildings, fences and trees for wind protection. At our home, the first thing we planted was a line of evergreen trees to the west and north of the property to block prevailing winds. Our neighbors put up a snow fence each winter to protect their fruit trees from the drying winter winds.

Heat Islands

Buildings and high mass walls or fences can absorb heat and sometimes reflect heat. This creates the microclimate that can protect plants extreme cold. For example, courtyards protected on all four sides in urban setting may be a full zone warmer than exposed areas. Espaliered trees are grown directly against a building or fence, to save space and use it for protection.

If you’re not quite ready to tackle an espaliered tree, try planting smaller plants or vines in the shelter of a building or fence. At our last home, we planted grapes along the southeast side of our house, and they loved it there.

Adjust for Sun and Heat

Plant relative to your location and the sunlight you need. Full sun is needed in the north, but you might want some afternoon shading in the south. Track the number of days you experience specific temperatures. Lots of hot days may permit a particular plant, or it might mean you won’t be able to grow a particular plant.

For instance, lots of 85 degree days might make it impossible to grow mountain ash in a zone even though the USDA map zone indicates it should grow. See “Summer Gardens – Dealing with High Temperatures in the Garden” for more tips on hot weather gardening. “Vegetables that Grow in Shade” can help you work with cool zones in the yard.

Water

Watch your local landscape. There could be a spot that tends to be more wet. Plant water loving plants in that location. Alternately, you can create water capture by adding berms or swales.

Slopes and valleys create a spot for water to collect, especially with mulch or other biomass at the bottom of the swale or valley. If you best spot for a garden has the right amount of sun and good access, but tends to be a wet spot, consider raised beds or additional drainage.

For more tips on dealing with excess water in the garden, see “Too Much Rain in the Garden – Managing Wet Dirt and Waterlogged Plants“.

Acclimate Your Plants

Plants that are locally grown are likely to be a better fit for your garden or homestead. For instance, a plant grown in Michigan probably won’t do well transplanted in Texas, even if the plant is “zone compatible”.

You may still be able to grow plants raised in another zone, but they might require extra care during the transition. This is called acclimating your plants to their growing conditions.

A very simple example is “hardening off” tomato seedlings. If you just put them out in your garden after growing them inside, the shock will likely kill them.

Even hardy plants sometimes struggle with unusual weather. Our zone 4 cherries didn’t like the late frost the last two years. They are “hardy” in our zone, but the plant could not deal with heavy frost after the tree budded out. This can also relate to seeds/propagation.

A specific plant might need more hours of cold to go into dormancy, and cycle into growth. A seed from Wisconsin might not sprout in Texas because the seed didn’t get its “cold stratification” in Texas, even if the plant can be grown in each location.

Keep Plants Dormant at the Right Time

The plant stays safe while dormant. Warm temperatures trigger a plant to break dormancy. If it gets cold after that, the plant can be damaged. Some plants benefit from wraps, much or protective covers that help maintain a stable temperature around the plant.

Covers are commonly used for small ornamental plants, like roses. We like to make sure our trees and shrubs all have a good layer of mulch to help maintain stable root temperatures. Some trees such as arborvitae get wrapped for winter.

Snow

Snow can be your friend as a gardener or farmer. A good layer of snow can allow some plants to survive because the snow actually insulates them from the severe surface temperatures.

Snow stays around 32°F which is a lot warmer than -20F. This allows areas with snow cover to sustain plants that would otherwise die if the snow was not there. Low snow winters in these areas that result in die off of otherwise “common” plants.

What are Your Goals for your Garden?

Your plant hardiness zone and microclimate combine to give you the starting place for your garden. The rest is up to your imagination and determination. We’re happy to help answer your gardening questions and share tips that we’ve gathered over the years, and we’d enjoy hearing about how your garden microclimate compares to the hardiness zone map. Just leave a comment below.

Hardiness Zone Maps Over the Years

Below are links to the various versions of the Hardiness Zone map, from the 1960s through 2012, including the three shown above and an alternate from 1967.

- 1960 Map https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/oc/graphics/photos/300dpi/kesa/d2493-1.jpg

- 1990 Map http://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/Images/USZoneMap.jpg

- 2012 Map http://planthardiness.ars.usda.gov/PHZMWeb/

- Alternate 1967 map https://arboretum.harvard.edu/wp-content/uploads/Hardiness-Zone-Map-1967.jpg

Related Posts

- How to Start a Garden – 10 Steps to Gardening for Beginners

- Organic Fertilizer – Feed Your Plants, Soil and Microbes

- Composting 101 – Easy Compost Making and Troubleshooting Tips

Last Updated: 2/9/2020

In Cosby Tennessee near the Smoky Mountains I established a perennial garden, but it’s Rocky (boulders). Are the Rock’s going to affect my plants? Should I expect the rocks to make the soil and roots colder (or warmer) in the winter?

Thanx, CRAIG.

One of our writers (Amber Bradshaw) and her family just moved near Cosby last year.

On the rocks – it depends. Rock walls exposed to sun are commonly used to trap and store heat to slowly release, so a large boulder in the sun may create a slightly warmer area near the boulder.

Similarly, a boulder in the shade may be a little slower to warm than the surrounding area.

The rocks will trap some moisture underneath, holding a little more on site reserves for dry spells. That moisture will tend to keep the ground a bit cooler – unless the rock gets hot enough in the sun that the heat transfers below ground.