Phytophotodermatitis – Plants That Cause It, How to Treat It

This post may contain affiliate links. Read my full disclosure here.

I’m sharing my story here so you don’t make the same mistake I did, and end up with Phytophotodermatitis (PPD). Phytophotodermatitis is also known as plant and sun dermatitis, parsnip burn, and sometimes lime disease (not to be confused with Lyme disease) or margarita photodermatitis. You get it from exposure to plant sap or juice and sunlight, as outlined below. We’ll cover plants that cause phytophotodermatitis and how to treat it.

This was not parsnip burn from exposure to some “poison parsnip” or giant hogweed. I was working in my garden. Garden parsnips and wild parsnips are the same species, and it turns out they can cause the same problems. Several other plants can cause the problem, too.

I originally wrote this post in 2014, and unfortunately ended up with another smaller case in 2018. I thought I was being careful, but apparently not careful enough.

The pain doesn’t start until days after sap and sun exposure. By then, the damage is done, and all you can do is treat the symptoms.

What is Phytophotodermatitis?

Medscape defines Phytophotodermatitis as:

Phytophotodermatitis (PPD) is a cutaneous phototoxic inflammatory eruption resulting from contact with light-sensitizing botanical substances and long-wave ultraviolet (UV-A 320-380 nm) radiation. The eruption usually begins approximately 24 hours after exposure and peaks at 48-72 hours.[1] The phototoxic result may be intensified by wet skin, sweating, and heat.

In other words, your skin erupts with blisters and itchy, burning red areas because you were in contact with plant chemicals (in this case, parsnip and carrot sap) and exposed to sunlight.

You don’t realize you’re in trouble until several days after exposure, by which point, you’re skunked. This is one of the aspects that makes PPD different from most other contact dermatitis. If you’re working with wet plants on a hot summer day, it’s going to be worse. (That’s what happened to me.)

If you visit the Medscape website, they go into a detailed explanation of how the chemicals in the plants that cause the damage (Furocoumarins) are activated in stages under different conditions, and how they actually damage the DNA of the skin.

You cannot “wash off” phytophotodermatitis chemicals with soap and water once they are activated by UV radiation. I did shower after working in the garden, but it didn’t do any good. Washing may help limit additional damage.

Is Phytophotodermatitis contagious?

Nope. Only those directly exposed to the problem plants and conditions experience skin reactions.

The only case that might be an exception is berloque dermatitis, a special type of phytophotodermatitis caused by perfumes. There are older perfumes that used oil of bergamot. (Bergamot is one of the citrus fruits that can trigger PPD.)

If one person applied the problem perfume and was in close contact with another person, they might spread the perfume – and the skin condition. It’s unlikely, but possible.

Which Plants Cause Phytophotodermatitis?

Here’s a kicker – there are wide range of plants that can cause this condition that you might never suspect.

Plants that may cause phytophotodermatitis include (but are not limited to):

- Parsnips (Pastinaca sativa)

- Carrots (Daucus carota subsp. sativus)

- Celery (Apium graveolens)

- Gas plant (Dictamnus albus)

- Parsley (Petroselinum crispum)

- Wild Parsnip (Pastinaca sativa)

- Queen Anne’s Lace (Wild Carrot) (Daucus carota)

- Giant Hogweed (Heracleum mantegazzianum)

- Limes (Citrus × aurantiifolia)

- Figs (Ficus carica)

- Chrysanthemums – Chrysanthemum genus, aster family

- Common Rue (Ruta graveolens)

- Russian sage (Perovskia atriplicifolia)

Those who are into botany will notice that the top six plants on the list are all related to each other (they are members of the Apiaceae family). Some of you may have also heard about getting blisters from wild parsnip or poison parsnip, but may not have realized the garden parsnips can also cause burns. Garden parsnip and wild parsnip are both different varieties of the same species – Pastinaca sativa. The veggies typically cause burns on agricultural workers and grocers, who handle large quantities of plant material.

The Medscape site shows a rather nasty blister that covers about 1/3 of the forearm of a flight attendant who spilled lime juice on her skin. The phytophotodermatitis from limes is also referred to as “margarita dermatitis” because of all those poor folks who have sucked on their limes in the summer sun.

The wild parsnip burns (and those from other wild plants like hogweed or queen Anne’s lace) can be some of the worst, because people do terrible things like running weed whackers with shorts on and get their legs all covered with little bits of parsnip (and sap), like the poor guy featured in the article “Burned by Wild Parsnip” in Wisconsin Natural Resources magazine. The photo below is as example of how large the blisters can get.

I’m Going to Stop Growing “Poison Parsnips” Because They’re Too Dangerous

No. I’m not. I’m not skipping the carrots, parsley or celery, either.

In all my years of gardening, these past couple of decades on my own and helping mom out growing up, I’ve never been burned by garden parsnip before. I did get about an inch long blister from wild parsnip, but none from garden parsnip.

Here’s what I screwed up:

I was working in the morning, so the plants were covered in dew. More moisture = wet skin.

It was hot, so I was sweating = more wet skin + heat, both triggers for phytophotodermatitis.

The area I was working on was roughly 80 square feet, very thickly planted, mostly with carrots and parsnips. I had thinned and weeded the patch when the plants were younger, but this round of thinning took place when the plants were a couple feet tall.

The only way to reach the roots to pull them out was to stick my arm into lots of foliage. (Lots of exposure.) I gathered up the bundles of plant tops after removing the roots with my bare arms. (More exposure.)

By the time I finished, it was pushing midday, with a bright, beaming blue sky = lots of nice, intense sunlight.

Would you like to save this?

In my 2018 case of phytophotodermatitis, I allowed queen Anne’s lace to grow in the greenhouse as companion plants for the tomatoes. I was trying to thin them out as the greenhouse became more crowded. It was hot, humid and sunny. I must have broken some of the stems, and got the sap on my hands and feet.

What I Should Have Done:

The simplest thing I could have changed was to wear long sleeves and gloves to cover up my skin. Problem solved.

Alternatively, not handling the broken plants with bare skin, or thinning harder when the plants were small so I didn’t need to stick my arms into a thicket would probably also have done the trick. That said, we have been enjoying the carrots and parsnips I picked. 🙂 No more wild carrots in the greenhouse. It’s simply too easy to get accidental exposure while working around the plants in close quarters.

How do you Treat Phytophotodermatitis

Like a standard burn, you can apply cool compresses to relieve the pain, and try to keep blisters intact as long as possible to protect the tender skin underneath. Over the counter itch cream like those for poison ivy may also help, along with anesthetic creams like Aspercreme.

I hit the pantry and the garden for treatment options.

On the first couple of blisters, I used fresh plantain and yarrow leaves, mashed and applied as a poultice. As more blisters showed up, I coated the worst blisters with manuka honey to promote healing and fight infection. You can read more about using honey for wound treatment in the post, “Honey as Medicine“. With over 30 blisters on my arms and hands, the honey was a little awkward to try and use on all of them, so I made up some comfrey salve with lavender essential oil.

I coated the burns several times per day with the salve, and at one week after exposure, some of the scabs fell off to expose new skin underneath. The burns on my hands and elbow didn’t heal quite as fast. My hands spend way too much time being beat up during canning and gardening season, so I can’t keep bandages on them, and the elbow is just awkward to keep bandaged.

Be patient. Badly affected areas may take weeks to months to heal, depending on the damage. I still have dark areas on my skin a year after exposure from the worst spots.

Comfrey and Lavender Salve Recipe

Adapted from the Herbal Academy

Ingredients

- 1 cup organic extra virgin olive oil

- 50 drops of lavender essential oil

- 1 ounce organic dried comfrey leaf

- 1 ounce beeswax

Directions

- Pour olive oil into a double boiler or small, heavy bottom pot. Add comfrey leaves.

- Heat over low heat for 60 minutes, stirring occasionally. You’re looking for gentle heat, not boiling.

- Remove from heat. Strain and compost comfrey, reserving infused oil.

- Melt beeswax in a clean pan over low heat.

- Once melted, add herbal infused oil and lavender essential oil. Mix well.

- Quickly pour salve into tins or glass jars and allow to cool before placing lids on and labeling.

The HANE website notes that “Comfrey contains allantoin, an anti-inflammatory phytochemical that speeds would healing and stimulates growth of new skin cells.” The HANE burn cream recipe also includes one ounce each of dried plantain, calendula and St. John’s wort to bump up the healing power a little more.

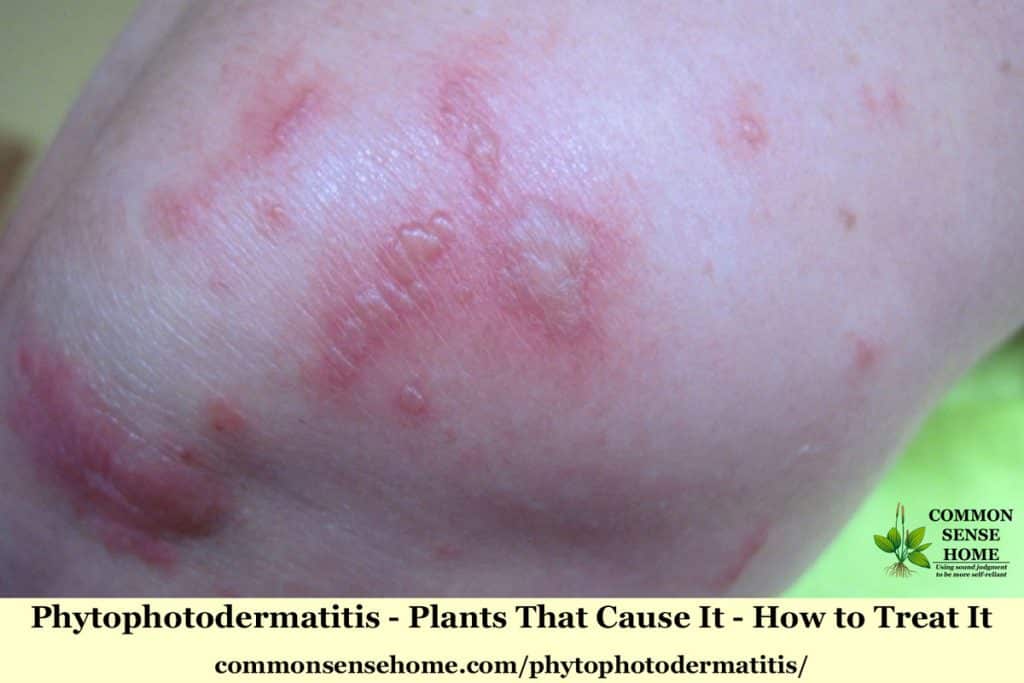

Photos of Phytophotodermatitis

Just so you can see how the eruptions progressed, I’ve included some comparison photos of the affected skin below. The image at the top of the post is my left elbow on day three after exposure. 24 hours earlier (48 hours after exposure), there was only one blister.

My left hand at day 3 and day 7 after exposure. Day seven may not look much better, but it feels much better. No more burning and itching.

One last shot. A blister on my right arm that was one of the first to appear that I treated with a plantain poultice followed up by a day of honey and ongoing use of the comfrey salve.

Don’t fear the plants, just don’t handle them in such a way that you set yourself up for some serious discomfort. Learn from my mistakes. 🙂

July 2019 – I’ve run into this again. After helping to clear an overgrown area near the greenhouse in shorts and a t-shirt, I ended up with blisters on my arms and legs. I didn’t see any queen Anne’s lace or other trigger plants, but they must have been in the mix.

I suspect repeated exposure may make you more likely to have a skin reaction.

The video below highlights this year’s exposure. (Make sure any ad blockers are off to get the video to display.)

You may also find useful:

- 9 Home Remedies for Dry Skin – Soothe Dry and Flaking Skin Naturally

- Grandma Called it Medicine Leaf

- Herbal Antibiotics – the Top 15 Herbal Antibiotics

Originally posted in 2014, updated in 2018.

Oh my goodness!! I am SO grateful to have found this site, and had the opportunity to glean from Laurie’s experience and advice. I Have been to 5 Dr’s one naturopath in the last 6 days. I was pruning and cleaning up old barberry, haydrangea, yukka, roses and other garden shrubs on the hottest day we’ve had so far this spring. After a shower, I enjoyed a long hot tub (and a lime margaritas LOL) and two days later broke out in about 10 red itchy spots in the crease of my left arm and forearm. I took a bleach bath. Over the next 4 days the very itchy ‘rash’ spread face to feet, red angry pigmentation, and eventually formed small oozing pimple like sores, some on my left foot have blistered quite badly. I’m on day 8 today. I’ve been put on cortisone cream and two strong antibiotics – which I am feeling very defeated about cause I know it’s wiping out my but and microbiome flora – which I work hard to keep healthy. No answers made sense (scabbies, staph or strep bacterial infections, shingles…) until the last dr came in and said, “oh yes, I just had another patient with the same thing – phytophotodermatistis” they put me on prednisone, and told me to stop the antibiotics and cortisone cream. The prednisone seemed to help reduce the redness a little and seems to have ‘mostly’ stopped new clusters of itchy popping up. I feel like a guinea pig, and the ironic thing is the morning my red itchy spots first appeared, I was starting my month long parasite, liver, metals, yeast and mold cleanse, launched it with a 2 day water fast. I had hopes that the fast at least would support my immune system to flush whatever what was in my system. It was just so odd how it wasn’t just localized, but as many others have shared, the ‘rash’ blisters spread systemically – in different parts of the body??? Any odeas on this, as opposed to only manifesting where the toxin was in contact with skin? So grateful for your site, love to hear any feedback or suggestions, and how to decrease scaring or darker pigmentation as it’s all over my arms, back and feet , hmmmph.

The information on phytophotodermatitis online is so sparse, it’s like everyone is copying off each other’s papers, and almost none of them have actually dealt with the condition.

I wonder if the bath might have spread the oils all over your body? I know that showering doesn’t get rid of it, so it makes me wonder if soaking might spread it?

Flipping doctors want to bludgeon everything with a sledgehammer. Lidocaine cream takes the pain level down if it gets too bad, or you can make up the comfrey and lavender salve, or a plantain and lavender salve. Cold packs help, too.

In my experience, all of it fades with time, even the scarring. Some topicals that might speed up the process include vitamin E, honey, comfrey salve, plantain salve, and aloe vera. There are also tons of different scar creams on the market. I’ve used honey, plantain, and comfrey.

Nurture you microbiome with as assortment of live culture foods, time working in good quality soil, and outside time in general. Contrary to popular dogma, we do need sun exposure, but you’ll want to be gentle with it while you heal.

It’s funny/not funny how we make plans to tackle one thing, and end up dealing with something else entirely. I hope your skin heals quickly. PPD is the pits.

I feel for all of you. late spring of 2022 I did everything a person could possibly do to cover much of my body with hogweed sap and mash.. I haven’t touched a weed whacked since. when I contacted Worksafe BC for answers they were very giving. At 63 yrs of age, and the massive amount of skin exposed to this chemical, their data base estimated my recovery time to be 4 to 10 years. They commented that the morbidity of this affliction was near the top of the scale.

I won’t burden you with my misery except to say I dont know how anyone could stand this torture. The only advise I was given was to avoid these plants completely. The hospital told me not to come in unless a secondary infection was brewing. There is really nothing out there to relieve the symptoms and no quick fix. The scientists know of only one little worm that chews Parsnip leaves, that has evolved to process this toxin with zero negative effects. oh they also couldn’t find an atomic half life for it. so once you’ve reacted as it seems we all have, you could pick up some dead yard litter and burst out again. I have keloid type scars all over the back of my calves, big hard bumps with no doubt some toxin encased in it just waiting to ruin my day. im healing. But im not healed yet. I feel self concious to show my skin, I toss my clothes every 6 mths or so because it attaches to the frayed seams in the washer and gets on me that way.. I try to feel sorry for myself on Thursday mornings between waking and 10 a.m. I cry about it and curse it out a lot. its too late for us but we can warn everyone we know so that they may be spared this nightmare. oh and two people have died from it. one fellow with type 3 diabetes and a young girl in New York State. not sure what her compli,cation was. I pray you all get through this and never ever get hurt by it again

Hi Sandra.

So sorry you are having to deal with this, especially such a severe case. I have found that Lidocaine cream dulls the pain some. I’m wondering if you could use oatmeal baths or bentonite clay to help draw out the toxins.

Thank you kindly for sharing such important information. I remember exactly when this event occurred in my garden handling celery mid-day and staying in the sun walking my dog after. My rash seems to be a bit different though. The blisters seem to appear randomly on different body parts. Even on my skull under my hair. The worst was on my face and neck. I had blisters on my fingers and hands as well. It is more spread out. I have found a new cluster daily for 4 days now. There is no pain, and the itching was managed with calamine lotion. Strangely, I got the flu the same day. At first, I thought it was poison ivy given to me by my dog. We have not found any poison ivy on the property. I found your information during my research. Thank you very much <3

I hope your skin heals quickly.

I am over 70 and have worked in the garden all my life. I have never had anything like

phytophotodermatitis (always grow lots of carrots). I always break the tops off with my hands when harvesting to feed to the horses and have never had any kind of reaction. The closest I have ever had is poison ivy and a reaction t o plant sap.

Is it possible that you and those who get this are allergic to the carrot sap? I once got a little sap on my wrist from a tropical plant and developed small spot of itchy blisters. I just figured I was allergic to the sap from the plant. Otherwise I have never had anything like it since (other than the poison ivy). The poison ivy occurred a few times when I was a kid but as soon as learned to identify it and remember to watch for it, I never got it again.

I am thankful for this post and will be more careful around the carrots. We all can develop allergies during our life time.

It’s definitely more than a straightforward allergy, but it does seem like some people are more sensitive to it. It also requires very specific conditions to trigger the blisters. I’d worked around carrots for decades with no issues, until I got in just the right conditions to run into trouble.

Can exposure to tomatoe plants cause this? And can it stay on you for a year? Last summer I broke out with blisters after being in the tomatoe plants. nothing would heal it. The Doc gave me steroid creme which helped but didn’t get rid of it. It burns, stings and itches at times. Lately it seems to be spreading. It’s been 10 months. Doctors can’t answer what it is. I have appointment with dermatologist but not till June.

Tomatoes don’t cause phytophotodermatitis, but they can trigger contact dermatitis. Dermatitis is basically a fancy way to say “skin inflammation by contact with something”. (Derma = skin, itis – inflammation)

Typically, contact dermatitis resolves within hours, or at the very most, days – once you’re out of contact with problem material. Since you’re still dealing with irritation months later, something is keeping your immune response in overdrive.

Our skin is our body’s largest organ, and our main detox organ. If there’s an ongoing flare up, things are working in the body quite as they should. Your dermatologist may give you a diagnosis of dermatitis, psoriasis, eczema, or something else, but in the end you need to do the healing, and topical creams can’t address everything.

I’d start with making sure that standard detox pathways are clear. Reduce or eliminate antiperspirant use. (Deodorant is okay.) Encourage sweating through exercise, detox baths, or IR sauna. If you can tolerate the sun (and have access), outside time in heat is good, too. If sun exposure makes the itching worse, avoid it.

If you have access to a rebounder (mini trampoline), use it. Rebounders are great for getting the lymphatic system moving to clear out waste.

Look at your diet and lifestyle. Any chance of food allergies or sensitivities, or extra stress lately? How frequently do you urinate and have bowel movements? There is so much garbage in our food supply that passes for food but isn’t good for our bodies.

Have you noticed more spraying in your area? Some municipalities now spray for mosquitoes and other pests, which leaves chemical residue for everything and everyone else, too. There’s also been more aerial spraying. Our skies look like a checkboard some days.

Have you made any changes in medications? Sometimes adding and eliminating medications can trigger skin reactions.

I dealt with psoriasis in 2015, 2016, and 2019, and am happy to say that my skin is now clear, but it took some time. At one point the itching and redness was so bad that I looked like a burn victim. After the main outbreak cleared, I had a brief relapse on my hands after I went off my medication.

My skin story and how I cleared it starts here – https://commonsensehome.com/psoriasis-the-year-my-face-exploded/

I’m wondering the same thing. I came in contact with tomato plants last September and everywhere the plant touched was itching and had blisters. I went in the garden in a sleeveless top and shorts. My arms, thigh, and elbows are scarred. I too got a steroid cream that didn’t really help. I had to use calamine every night and that’s what gave me relief. I too have an appointment at the dermatologist in June. Nothing seems to get rid of this scarring.

As noted, that’s likely contact dermatitis, but it’s unusual that it would last that long. Plantain leaves, jewelweed, chickweed all have soothing and drawing properties and may be of help if you have any of them available for a poultice.

Wonderful advice. Wonder if anyone else tried applying stinging nettles to the area. That worked for my husband who had been affected numerous times.

Interesting. I’ve heard of stinging nettles for arthritis, but not phytophotodermatitis. How did he apply them, as a poultice?

Tecnu. Helps better than anything to get the sap out of the skin.

I see that it’s listed as a poison ivy soap. Does it help after blisters show up, or only to remove sap after initial exposure, before blisters show up?

I got skin blister and itchiness from contact with lime tree and sun exposure, while trimming lime tree without shirt on. I noticed the reaction only on my bare chest, back, and not any other part of my bare skin, arms and hands.

Thank you for the info. Wild Parsnips are spreading like wildfire in the U.P. I came in contact with it about a week ago after falling off a log and accidentally grabbing this plant and now blisters are appearing on my hand. One went away, but another on has came out right next to it. They are like burns , that itch. The second one is leaking fluid. Pretty ugly, but now I know what to stay away from.

Watch out for the Queen Anne’s lace, too. Our yard is loaded with it this year.

I hope your hand heals quickly.

Thank you so much for posting this. I have a bumps, streaks, and blisters that look exactly like these pictures which developed over a period of days after I went strawberry picking followed by several hours of biking in the sun after being drenched by a rainstorm. Not sure if strawberry plants are the culprit or another plant I was exposed to, but after seeing several doctors who thought it was impetigo then poison ivy (even though I haven’t been around any), this explains all of my symptoms much better, making me feel much better!!!

Sorry you are hurting, but glad you found a match for your symptoms, and I hope it feels better soon. As you and many others have found, most doctors don’t easily recognize the reaction.

Strawberry plants aren’t known to cause phytophotodermatitis, though sometimes they do cause a rash in sensitive individuals. What you’re describing sounds more like PPD, so it was probably another plant.

My exposure that I thought had “healed” returned 3 years later after receiving the J&J Covid vaccine.

It’s possible that it somehow triggered something from the original exposure, but I’ve seen reports of skin issues with the jab from those whole never had PPD. You should probably check in with your healthcare provider, and have them register the issue with the reaction database.

I’ve been getting this every year for the last 4 years or so and I could never figure it out. The DR I see at the VA wasn’t sure either and just recommended an anti itch cream. Thank you so much for sharing this!! Now I know I get it from weeding in my yard and trail running. Running and sweating always seemed to make it worse, but that didn’t make any sense to me… Now it does!

I’m glad you found us and now have a better idea of what to avoid. Lots of doctors are confused by phytophotodermatitis, and because the blisters show up well after exposure, it’s tough to pinpoint the trigger if you don’t know what you’re looking for.

Is aloe on this list? And do antihitimines help?

Aloe can help with the burns. Antihistamines are not likely to be of much help, as it is a chemical burn.

Thank you so much for your post!!! LOL I thought shingles broke out on me but it came out after I worked in my garden and I didn’t get the connection! —- Parsnips greens. I love parsnips but never knew and I live in Florida!! The rashes were in places that didn’t make sense for shingles! Left ear. around the chin and mouth and on my writs and underarm near the wrists! they are in a pot which I moved! They were high growth, hence the leaves hitting my neck and ear as I picked up the big pot and moved it to another place. I’m keeping it. I used dead leaves to put around my pepper plants and want to see if it will keep pests away! That is what the parsnips plant is doing!! But now I going to buy long garden gloves and NOT move the pot with my face in it! WOW! thank you!!! No need to get a vaccine for shingles! I’m thrilled!

I’m glad you were able to find the site and find an answer to your mystery symptoms. The blisters are pretty miserable while they last, but thankfully they do heal without medical intervention in most cases.

Found this too late. I worked with figs, parsnip, carrots and parsley all on a sunny and super hot day… two days later i woke up with blisters on my arms (top and bottom over 50).. looked like someone splashed me with acid. I thought it was from the fig sap. Month later, more blisters appeared (not too many).. so I was like.. but I didn’t touch the fig? Only plant I worked with was parsnip (first year growing it). Crazy. Two weeks later.. my mom got also a blister although she was being careful given what happened to me. I enjoy to eat it more now (my revenge haha) and considered not planting it again – so thank you for the ‘how’ to stay safe 🙂

At least now you know and can be more careful in the future.

Thank you for putting so much thought and information into this post! I have discovered my own sensitivity to Virginia Creeper. After doing some research I found that this vine contains oxalate crystals on the leaves and can, in some people, create an allergic reaction very much like the urushiol in poison ivy.

I try very hard to not come in contact with plants I have noted that are not friendly to my skin – your list and information is very helpful!

After being very careful myself I would add that ; I have to be even more diligent as any stirring of offending plants (mowing) can put the irritants in the air and still give me a reaction (usually mild though). This year I handled my husbands clothes after he had been in a lot of growth and from the secondary contact have developed a bad breakout.

What is even more frustrating is that it will trigger a response in areas I previously had the rash (I guess that is systemic or neurological?). So, it is not just the exposed area . But seemingly my whole body reacting to one exposure 🙁 .

That said I am very interested in digging a little deeper into all the information you have provided. It can be hard to find and you did a wonderful job.

Thank you!

I ran into Virginia Creeper trouble this year, too! We had some try to strangle a rose and sneak into the greenhouse this year, and I’m 99% sure I got a streak of sap on my forearm from the roots that had me dealing with PPD again. I wore gloves, but it was crazy hot in the greenhouse so I had short sleeves. One of the roots whipped up and smacked my arm as I was pulling.

I’m so thankful you shared your experience, because no one dealing with this seems to share much information online, especially those of us who have gotten exposed more than once and from incidental contact.

I don’t know if someone has already asked this, but could medications that make you photosensitive be a factor in this? I have been hiking and romping half of my life in a certain wooded area in WA state with cow parsnip, Queen Anne’s Lace, Meadow Grass, and poison hemlock. I have never had ANY sort of reaction, but within the last 2 months started taking duloxetine (antidepressant, anti anxiety) and all of the sudden am having an intense reaction after having lied down in a meadow playing a game with my kids.

I don’t believe the question has been asked, but it wouldn’t surprise me at all if they also increased the risk for phytophotodermatitis.

From RXlist duloxetine side effects listing:

(But you probably guessed that yourself, since you mentioned photosensitivity.)

I can’t find anything online that confirms a connection, but many doctors don’t even know phytophotodermatitis when they see it.

I have no experience with this rash but do have a lot with poison ivy. We have a large family and live in rural Michigan. I have found the best treatment on exposure is washing with cold water and a lot of soap followed by liver boosting herbs like dandelion, milk thistle, etc. My children rarely get whelts or blisters anymore. We just drink a tea or take a supplement guided dosing by the return of itching. Hope this is helpful for someone.

Thank you for sharing your experience.

Hi, thanks for the article. I have this from pulling out morning glory vine. Was not thinking when I reached down to remove the small vine. One vine lead to another and now my hands are covered in blisters that itch and are very angry.

First day there was just a blister on one finger so I covered it up so it wouldn’t get bumped. By day 3 it’s angry, very swollen and painful and there are many more. My whole finger is a mess.

I googled it and the only article I found to confirm my guess was yours. I appreciate the info. Didn’t know the sun was a factor.

A few years ago I was pulling out the same stuff and it started to rain. It made it cooler so I kept gardening. I guess the wet vine slung sap in my eye because a day later it was horrible with a chemical burn. A trip to the eye doctor, drugs and $150 later it improved over a few weeks. I hadn’t remembered this incident when I started to pull weeds. Thanks again for sharing.

Hi Donna.

So sorry about your eye. That must have been so painful.

One of the worst things about phytophotodermatitis is how the pain and blisters build over several days. I haven’t found independent data to confirm this, but it seems like the pus from the blisters can spread the burn (at least, that’s what it looked like on my arms last year), so be extra careful to try to not spread it around on your finger/hand if you are able. (Next to impossible when you keep working, I know.)

I hope you heal up soon.

Hi, I came in contact with large philodendron plant that had grown around a tree we were cutting down. I now have what looks like a poison oak rash. Can philodendron plants cause this also?

It looks like philodendrons can cause contact dermatitis, not phytophotodermatitis. Still irritating, but hopefully it will heal faster than PPD.

Can anyone describe the symptoms in detail for me, and by symptoms, I mean the sensations in the sores or wounds? I have two blisters. I have no clue where they came from, but I was pulling up weeds beside the house two to three days before these erupted. They itch, and about three to four inches around them itch intensely. More importantly though to me is a weird, very warm tingle that is accompanying them.i even have the three to four inch area around them constantly tingling and feeling warm from the inside and radiating outward. It is a weird feeling. The only thing that has helped so far is Jewelweed cream that I bought years ago (it is actually long expired) that has plantain and a few other herbs in it. I would love some input on the sensations that everyone has experienced, especially if anyone has had the weird tingling too. Like nerve tingling.

I haven’t had what I would call nerve tingling, but I have had the area effect itching. When I inadvertently broke the blisters while scratching (or when bumped), the area exposed to the blister fluid also reacted.

I’d describe the discomfort from exposure (at its peak) as mostly intense burning and itching. This year I even broke out some Aspercreme with Lidocaine to dull the intensity of it because my legs below the knees and forearms were completely covered.

Thanks, Laurie. I don’t have any comfrey handy but I can give the cabbage poultice a try. Is there any advantage to a particular color of cabbage being used?

Not that I know. I think any will get the job done.

Hi Laurie, Thanks for creating this discussion. I think I may have found an answer to my dilemma! Almost a week ago, I noticed a slight burning rash on the tops of my feet, the right side much more predominant. I was at work and noticed the friction of my right shoe/sandal rubbing against the skin was really irritating it. At first I thought maybe an insect bite but there was no itching just burning. By that evening and the following morning it had blistered on the right side making shoes incredibly uncomfortable to wear.

I live in Hawaii and had family visiting last weekend. Before this started we went to the beach, I sat under the shaded pavilion. We went snorkeling and again was under the shade on the boat. I had ruled out sunburn and it wasn’t acting like a typical sunburn (for me). Initially it was thought I picked something up from the snorkel fin.

The cause still felt like a mystery to me even after going to Urgent care and talking with my doctor. They said whatever it was, was behaving as a burn. Urgent care gave me burn cream but it didn’t change anything. My ND suggested Lavender oil and raw honey. After a conversation with a friend and noting the shape and location of the “burn”, just under my slippah (flip flop) strap, I realized that is where I put a drop of Bergamot essential oil most days – a photosensitive oil!

I recently changed brands, but it seems more like the circumstances of having it on my skin, probably some residual oil on my shoe strap, and exposure to the intense UVA rays during the summer here all contributed. The suns’ rays are intense this time of year! Could have happened on the boat after my feet were wet..??

Walking around with my foot wrapped aggravates it. I got some Manuka honey yesterday and started applying it, it feels good on and I was able to walk flat footed for the first time in 4-5 days, but not much change in the red color or painful big blister yet. I will stay hopeful!

Cool water foot baths and Aloe have also been soothing but not much change in appearance. Thanks again for the post! (Any thoughts of when to get something stronger if no change?)

Be patient. It sounds like you’ve effectively given yourself a chemical burn that goes deep into the tissue, and it will take a while to heal.

You may want to try a comfrey poultice, if you have some available, or a cabbage poultice or drawing ointment, to see if you can pull some of the residual oil and swelling out of the tissues and speed healing.

This has to be the oddest thing! I have been gardening since shortly after the Earth cooled, and have never even heard of this! Is it possible some people are immune? We pretty well grow all the vegetables listed, and have never encountered any of the listed symptoms!

lol – I haven’t been gardening quite that long, but I never had an issue with it in the garden until just recently. Thankfully, as noted, the conditions have to be just right for phytophotodermatitis. I do suspect that some people are likely more sensitive than others, but with enough exposure in the right conditions I think anyone would have trouble.

I chopped down a large century plant in my mom’s back yard… the sap not only made blisters all over my hands and arms, but burned holes in my clothes! Luckily, washing took care of it, though the blisters had to run their healing course.

Yes, Century plant (Agave americana) is one of those that causes phytodermatitis, not phytophotodermatitis – no specific sun exposure required, although some conditions can worsen the reaction. Sorry you had no warning until you were exposed.

The Washington State Department of Labor and Industries has a huge list of plants that cause phytodermatitis. Agave americana is listed in the mechanical and irritant categories:

I did the same salve for my exposure. It healed to a point. Then I tried Reversol 8% alpha hydroxy acid. It’s only been a few times, but I’ve seen improvement. I think the acid in it restores the skin’s phbalance.

http://www.reversa.ca/index_en/04_skinsmoothing/04_skinsmoothing_01.html

*this cream is not for use in the sun*

*wash it off before sun exposure*

When my blisters reappeared I used 1 bottle Hydrogen Peroxide + ¼ cup baking soda as a wash. I sloughed off the dry skin and reapplied the wash until the skin wasn’t dry anymore.

Also I tried a poison oak remedy: a paper bag soaked in apply cider vinegar and applied as a poultice for 10 min. So far so good.

I am on day 6 of phytophotodermatitis after trimming alders in a possible young hemlock bed while camping. I thought I had mosquito bites, and scratched under the blanket all night. Zinc oxide allows me to function in the garden. I am thinking of throwing away the blanket from camping. I’m afraid the hemlock oil may be spread to other clothes via the washing machine. Am I just being paranoid?

From what I’m seeing, it doesn’t look like the sap that causes the irritation would spread in the washer. It’s not an oily type of sap. To be extra cautious, you can use plenty of detergent, a double rinse, and wash is separately from other laundry.

Good timing on this article for me as I will have carrots to pull soon. It’s also a good reminder to wear long sleeves and gloves while picking veggies.

I tend to be sensitive to squash plants (not as much now as years ago) and my ex-MIL was sensitive to Okra plants. No blisters for either of us, but itchy red skin. She always recommended wearing a light weight, long sleeved shirt when harvesting and it really worked. I tend to be in shorts and a tank top these days, but will at least try to remember when I pull my carrots.

A number of garden plants can cause contact dermatitis for sensitive individuals. Nightshades (tomatoes, okra, potatoes, etc), beans, and cucurbits (squash, cucumbers, melons) and weeds like ragweed (that one gives me itchy bumps). I like working barehanded when possible, but like you, sometimes I need to cover up for safety. My eldest gets congested from working around thickly growing tomato vines.

I’m new at all this… So if you need to be careful of the broken stems/sap is it okay to feed the tops to the chickens? Or to let them forage at the end of the season?

Poultry doesn’t seem to be bothered, at least not that I or my poultry friends have seen. If tops are being ingested, the sap doesn’t get exposed to the sun.

I suffer from PPD caused by parsnip tops.

I haven’t always suffered, it first happened about 8 or 9 years ago, before then I was fine handling parsnips.

What has changed?

Why did I suddenly become allergic to parsnip leaves?

Is it possible to reverse the condition?

The sap of parsnips is always capable of causing PPD. It’s not an acquired allergy. The trick is whether or not the conditions are right for the reaction to take place.

I’ve handled parsnip and carrot greens for years and never had a problem – until I did. You only see the reaction when all the different factors come into play, as explained in the post. Moisture, sun exposure, and sap are the key factors.

I have very sensitive skin. I also have seen 5 doctors. No one seems to be taking it seriously. I’ve suffered now for 1.5 years. Yes YEARS. It looks like your pics but mine had kinda hard white heads (like acne) in it. My Dr says my body is trying to push bacteria out thru my pores. He doesn’t know of this plant, YET!!!!

I was given a steroid cream. Made a terrible mess. I was allergic to the cream the steroid was in. Made my skin so hard, it looked and acted like I buffed my arms with rainX. Nothing was gtn or out of my skin. Dr had to correct that problem first .

Now it seems to have started to spread again. Its winter here. At lease 1ft of SNOW!!! Can anyone help me?

It is painful to get wet from my hands to my feet. It hurts if my shirt cuff rubs on my hands. I can’t let anyone even touch me it hurts! I think the Dr’s think I’m a drama queen. That is false. They say they see dry unhappy skin. My friends see it. Its there. I even record any changes with my camera. Pictures are there not imaginary.

They even said I need to see a psychiatrist for my stress. One said I did it to myself. YUP! I sit on the couch eat gallons of white nonperrels until they a popping out of my skin, watch a movie and peel the skin off my arms and hands. Not just until they bleed, but to the 4th layer.

I showed up at my own Dr’s Quick Care. They took one look at me and made me stand OUTSIDE the building! They didn’t know if I might be contagious. Someone out there…. please help me!!!! PLEASE PLEASE. This is not a joke. I am living this!!!! I have many pics!!!! to prove all of this.

I’m not a doctor, but I understand your pain. Let’s talk about some possible causes.

If you’re in the middle of winter, I would think it would be very difficult for you to be exposed to one of the problem plants. If you were exposed to a topical irritant, the reaction shouldn’t last for a year and a half, unless you keep getting exposed. Is there any chance that some product that your skin is exposed to may be causing the reaction? Is there any product that only touches the affected areas? If so, eliminating this would be a place to start.

Could you possibly have a food allergy? Sometimes the manifest in odd ways. An elimination diet would be a way to test and see if you are sensitive to specific foods.

Have you considered candida overgrowth, coupled with pustular psoriasis? If you do an image search on pustular psoriasis, some of the images look very similar to what you describe, like this one – https://www.medicinenet.com/image-collection/pustular_psoriasis_picture/picture.htm

A couple of years ago, my skin went nuts. I looked like a burn victim. Different areas all over my body got thick, flaky skin that would peel off until it oozed and sometimes bled. It hurt to breathe or smile because my face was in such bad shape. I went to the dermatologist, and she said it was just psoriasis, gave me some steroid cream and told me to live with it. That was not acceptable to me. I got allergy testing done, and found out that I had candida overgrowth. I changed my diet and used some other alternative treatments, and my skin is now completely clear. I ended up writing a series about the experience, which starts here – https://commonsensehome.com/psoriasis-the-year-my-face-exploded/ There are photos of different areas of skin throughout the series. I haven’t updated it recently, but it all ended up clearing except for a tiny bit of rough skin on my elbows. I did have psoriasis, but the candida was the trigger for it.

I hope this is helpful. I know what it’s like to suffer in your own skin.

Your desperation and frustration are heard, and as someone who struggled with increasingly extreme rashes, itching, oozing skin, pain and periods of extreme fatigue and mental fog from 12 years of age until my mid-50’s, it is understood.

Laurie’s journey through seeking help, being pointed through a lot of wrong doors and then resolving to work it out even if she had to do it on her own is a a bit different than mine, but it does underscore that contemporary Western medical training could use some overhauling. It takes a strong will to withstand the suffering you are going through and still pursue a solution. It took many people, a few of them MDs, who looked to traditional and innovative therapies to sort our what was happening to me.

In my case, a case of flu was treated with penicillin in doses far too high for a child of 8 years. This appears to have killed off my digestive flora and pretty well stopped up my digestion. More people in our society now know that digestive flora are an important part of our immune system. Undigested food ferments in us, inspiring the yeasts, bacteria and parasites we naturally carry around with us to multiply and try to digest the rotting food for us. They are really only there to help out if our natural gut flora briefly get a bit behind.

I had a good appetite as a kid, and until that inappropriate medication for flu was pretty healthy except for an allergy to mosquito bites. In the 60’s, talking about digestive problems was considered poor manners, and doctors didn’t ask about it, especially with children. As the years went by the festering undigested food began to overwhelm my intestines, liver and kidneys. Traditional practitioners know to begin looking at digestive issues when the see skin problems, because they have recognized the relationship between healthy skin and healthy organs. Ayurvedic practitioners say that health begins with the digestion. Laurie discusses this in a discreet way.

Since you are so uncomfortable, you might want to think about how common it is for you to drink 48 to 64 ounces of non-chlorinated water (if you can manage it, artesian spring water is probably the finest form of water for healing) per day, and whether you move your bowels at least once with gold stars for around three times a day. Think of it as food in, garbage out There are specific details on finer points of this aspect of our daily health routine in Dr. Bernard Jensen’s books on digestive health. It gets pretty graphic, and that is because a return to health may depend on it.

You might also find it helpful to think back to whether you went through a period of notable stress before the rash began and if that stress has been managed or passed. Sometimes a toxic exposure can overwhelm us if we are not in the best of health. Were you exposed to a lot of sun, plant matter and/or atmospheric or food stream chemicals not long before the rash appeared? If you want the help of a traditional or holistic health practitioner, be prepared to go through an exam and at least one session where you talk over your experiences with the practitioner. Some are good listeners and some are not.The good ones may not use flashy techniques, but they do take time to understand your health history and what was going on when you began to experience symptoms.

It may take a few weeks before the level of toxins in your bloodstream reduces enough that your organs can manage them internally. The first thing I noticed was that my bowel became regular, elimination became more comfortable and I was sleeping better. Good sleep is a clue that your body is beginning to heal. Arrange to get plenty of sleep and time to rest.

For most of us, if we can get those basics re-established, our natural healing abilities will take over, and at minimum we can turn our minds to accelerating the process by seeking knowledge on how to take proper care of ourselves. It takes a strong person to go through what you have, and it will feel so much better to apply that strength to healing. And with skin, once we figure out how get pat the problem, it can heal quite rapidly. Good Luck. Healing is one of the greatest adventures we can have!

I am experiencing this right now. Thank you so much for sharing your story. It has been very scary for me and also a little difficult to find similar stories out there. I was pruning fig trees and warned not to get the sap on my skin. Thought I was being careful but it turns out, you need to be VERY careful and cover up any exposed areas of skin. I have been left with blisters all over my arms and partially on my legs. This was seven days ago- blisters have gone down and are no longer painful ( I used Aloe Vera gel and this seemed to work fairly quickly). I am now left with deep red marks in strange shapes all over my body. Have been feeling pretty devastated about it and so worried about scarring, but this post has made me feel less alone!

At least now you know and can be more careful next time around. Take care of the affected areas, and over time they should heal and be scar free. I can’t even tell where all the blisters were on my arms now. I do think the salve helped speed healing, because the more recent burns that I treated with the salve faded much more quickly than the burn I got many years ago. That one eventually faded, too, but it took at least twice as long.

This is great news, I will try it!! Thank you again.

You’re welcome.

Hi Laurie,

Thank you for your post, the pictures and information was helpful.

Recently I got into a mulching project that got me into lots of Poison Parsnip. With the information you provided, I set up a treatment of Colendula oil and a salve of Burdock root, Comphrey,

Chickweed, Echinacea, Plantain and St Johnswort. For 5 days straight I kept the affected area (my hands) out of the sun by always having dark, sun blocking gloves on and repeated applications of the Colendula Oil and Comphrey salve. It looks like I have prevented the worst from occurring. The sites where one would expect blisters there are only dark spots that look as if they have scabbed without blistering. I have recently had Poison Parsnip on my foot and that site, with out treatment, blistered, the skin peeled off and the skin underneath was dry and red. I was especially concerned that my hands would suffer the same affects. So far, day 5 now, it looks like i have dodged the bullet.

Thank you.

Glad you were able to prevent worse damage. I was sloppy this year while I was out with the ducks hunting for slugs, at least, I think that’s when I got exposed. I was pulling weeds around the compost bin. The next day, I had two small blisters on the outside edge of my hand, just below the pinky finger – right where the broken off stem of wild carrot that I pulled would have hit. Since they were small, I coated the area with manuka honey and a bandage for a day. That drew down fluid in the blisters and they’re healing nicely.

My both hands are covered in parsnip rash , worst on the finger tips. Mine was cause by parsnip that I’d left go to seed , I cleared them on a sunny spring day , pulling them up and chopping the foliage up into my compost bin. The sap only turns toxic after the plant has flowered and gone to seed, I’ve had this problem every summer for the last 6 years and because it all over my fingers and hands it stops me from doing the simplest things. Its the equivalent of third degree chemical burns and there’s nothing to fix it, I have to wear white cotton gloves to avoid infection and also to not freak people out, my hands look like I’ve tried to remove my finger prints.

Wear gloves x

The sap can cause the phytophotodermatitis at any time in the life of the plant, given the right conditions. My plants were young, basically large seedlings.

Please cover up the next time you need to deal with these plants.

Thank you so much for this. I am actually going through the same right now. Mine was from trimming my Rue plant. I never imagined it was that as I trimmed the plant the day before and usually reactions start within a few hours. It started off looking like hives on the first day with some slight tingling but not itchiness at the time, the next day it looked like a rash, by the 3rd day it blistered a bit. Since I mostly used my right arm and had it way in the plant trimming close to the trunk, that is the most affected. Some of the blisters look like they’ve popped. It got kind of itchy and when I would accidentally scratch it it felt like a bad sunburn. I was wearing shorts and I did get a bad blister on one knee that is still there but no longer painful to touch. I know Rue is loved by the Yellow Swallowtail caterpillars, and one year they nearly ate the whole plant, just leaving the bare stems. Today is day 4 of exposure and it has started to get a bit itchy. I’m just applying my anti-itch gel that helps. Thanks again!

Thanks for sharing your experience, although I’m sorry you have to go through it. I think one of the worst parts of the situation is how you have no idea that something is wrong until there is nothing effective that can be done other than to treat the damage.

This just recently happened to me and gave me the scare of my life. Last Friday I climbed a hill and encountered a lot of snakes, so I was worried if one of them might have bitten me without my noticing. After a few hours and no symptoms I figured I was safe, but the following day a big red scratch appeared on my hand and I thought it was just a scratch, even though it wasn’t there the previous day. As the time progressed, it started burning a lot and blisters started appearing. They were getting worse by the hour. At one point I was sure that I got bitten by a snake and rushed to emergency hoping that I wouldn’t lose my hand. Fortunately, when I got examined, the doctor said it was probably a reaction to some poisonous plant. I searched online and found your website, and your pictures look exactly like what happened to me, except mine was worse. It’s still in the process of healing and I guess it will take some time.

Yes, it will take some time to heal, but as long as you care for it properly it should heal without a scar.

My daugher and her friend were making “perfume” out of orange, kumquat, petunia, geranium, orange blossoms, snap dragons and boganvilla flowers. Then they went swimming in the Phoenix sun. They both developed blisters on their hands andmy daugher on her face, neck, shoulders, arms, legs and feet. She must have more sensitive skin than her friend. Their skin look just like your pictures. Thanks for the information! I think this maybe what they have. Pediatrician was concerned she had a systemic bacterial infection and prescribed anti-biotics.

Oh no! Poor girls. Hopefully it was just phytophotodermatitis, and once they heal they’ll be back to normal. Make sure to get her on probiotics after she finishes her antibiotics (or sooner, if okay with doctor).

Please beware of morning glory also. I have been battling a dermatitis/infection/steroid nightmare for 6 years at its peak the skin on my hand gloves off 6 times and my feet go bed off 3. I weeded morning glory out of garden bare handed and bare footed.

Last summer my daughter repeatedly broke out with something very similar. Doctors said allergy to something, eczema, etc, etc, nothing helpful. They actually insisted I stop using my plantain/calendula salve and homemade body butter on her and buy some very expensive “special” soap and lotion products.

I narrowed it down to probably contact with green bean plants (no allergy to green beans themselves) which is apparently also very common. She loves to pick them every afternoon. But, we had carrots planted next to the beans, so this year I’ll be looking at that as well. Thanks for the info!

My neighbor’s daughter breaks out in hives from contact with potato foliage. When I went into the dermatologist for a different skin problem (psoriasis), they told me the same thing (don’t use homemade products) and gave me a shopping list of products that looked like an advertisement for Proctor and Gamble. I tried their way for a couple weeks, and things got worse instead of better. I switched back to my regular products, and instead did an overhaul of my diet and added some different herbal teas to the mix. My skin cleared up. I think you’re on the right track to watch closing for what’s she’s in contact with to pinpoint the allergen.

I just happened to come to your site by chance and I’m pleased that I have. Thank you for sharing this post, I have never heard of this before. I’ve been growing vegetables for many years and I have thankfully never encountered this problem and hopefully I won’t ever now. I shall hopefully learn from your mistake and keep my skin covered when working with parsnips, carrots etc…

I found your post to be well written and very informative so thanks again.

Today my ankles and feet broke out in a rash and blisters. Google images came up with one of your photos – which closest resembles mine.

On the weekend I mowed the lawn and attached a small fig bush with the weed wacker- in the heat. I was covered in grass and sap – I’m paying the price now! At least I learnt a lesson about the fig sap.

Thanks for sharing this useful information.

Ouch! I hope you heal quickly, and now you know to avoid it in the future.

Hi, I have been dealing with this first on my legs, and now on my arms. It was misdiagnosed several times and I ended up in the ER in Bogota Colombia where I was given an anti-biotic that I’m apparently allergic to and I got hives. It looked like I had some terrible, nasty, life-threatening disease on my legs and I’ve not seen yet pictures that look as bad as I did. I do think now it is Wild Parsnip, but I am also thinking that the repeated exposure to sun even without the plant exposure made it much worse. I am also sensitive to extreme heat (anything over 80 now with the humidity) which is a real bummer since I grew up spending all summer outside and swimming.

My question is, do you ever use Coconut oil in place of the Olive oil in this recipe? How about adding Plantain, Golden seal, Echinacea, Calendula, Evening Primrose Oil, Tea Tree oil….etc… to this recipe? I’ve just been going thru books, the web and other notes I have on herbs, homeopathy, essential oils, ETC to see what will help. Thanks so much.

You could use coconut oil, but the salve would be much thicker. If you wanted to add other ingredients, I would only add one at a time. Be careful that you don’t make things worse. Sometimes less is better.

Good thought, thanks. I do tend to go quite overboard, sometimes making it worse before it gets better. Am making this today….

I tend to be very sensitive to a variety of things, so I always try to keep my remedies as simple as possible. Good luck.

I recently spent a weekend at my daughter’s home in VT where I first heard of the dangers of wild parsnip that is in the fields adjacent to their home. I had occasion to be in those fields and on the morning after returning home I had what appeared to be a cluster of bug bites on my cheek–not itchy and not painful and did not present itself like poison ivy with which I am very familiar. But over the next few days other little itchy blisters began appearing on my hands, shoulders, etc.–similar to how poison ivy often spreads on me. My cheek continues to look very red and but no huge blisters or pain. Does a reaction to wild parsnip appear all at once or can it take a week or so for all infected areas to break out?

In my experience, it all erupted within a short period of time. The sap isn’t oily, so I suspect it dries and stays put, unlike the oils of poison ivy, which readily transfer from one surface to another.

Oh, count me in on this one – discovering hogweed on a hiking trip and not being aware of its effects, I explored it for a while… It was July, sunny day, and it rained afterwards – all of them aggravating factors. Next day, I discovered reddish area on my hands and face, thought it was some burn, which will develop scabs and heal. But no – two days later, it just darkened. Then I visited a dermatologist and discovered the cause and extent of the situation. Luckily, I didn’t developed blisters and it’s not painful, but three weeks after I have some pretty visible hyperpigmentation on my hands and face. I hope it will recede eventually, but it doesn’t really seem like it now. What an irritating plant/s (no pun intended :)!

I’m glad that you didn’t get the blisters. Those were the worst.

Hi there, the moment I saw your pin and the associated picture I was shocked – I had exactly the same type of reaction to the top of a pumpkin stem when I picked a pumpkin from our garden. It took a few days for the blistering to appear and could not figure out what had caused it as it looked like a burn from the oven – wracking my brains, then it dawned on me – when I picked the pumpkin I felt a few prickles but nothing much – but the burns were exactly where I had rested the stem. There was no point doing the usual burn treatment of running under cold water as the blisters were already there so I just used burn cream. It took weeks for the burns to clear up and in the end to help the healing process I was taking a silica supplement. So no more picking pumpkins for me – hubby can do that from now on. The scaring has finally healed but it took a few months. I did notice though that pumpkin is not on your list – maybe I just have extremely sensitive skin.

I’ve gotten pumpkin sap on me a number of times over the years, with no reaction other than minor redness. I suspect you may have had an allergic reaction.

Hi Laurie, thanks for your post. I have a terrible phytophototoxic rash on my hands from squeezing lemons – I’m an herbalist and did not know they contained furanocoumarins! My hands look awful. The initial reaction has almost subsided but now there are huge blotches of hyperpigmentation remaining. I’m curious how long the residual redness from your rash lasted/does it still persist? I’m reading about the more conventional ways to treat the hyperpigmentation but if you found herbal preparations successful I would much prefer them. Thanks again!

The marks were pretty much gone after a few weeks. Of course, since it was summer, I tanned over the top of everything. Since my modeling career has been a little slow (haven’t done any of that since college over 20 years ago) and I’m not in a job where I work directly with people all day, I didn’t look into treatments for the skin discoloration, only the pain.

Just as parsnip and wild parsnip are the same species, so are carrots and Queen Anne’s Lace the same species (Daucus carrota).

Do you know if Queen Anne’s Lace will cause this? If so, perhaps you should add it to your list, as people are likely to make the same mistake of weed-whacking in shorts.

Yes, wild carrot may have the same effect. Thanks for the note.

Is the comfrey/lavender salve good for other skin issues? I’d like to have it around if it is…

How long do you think it would last in the refrigerator?

Yes, the salve should soothe most minor skin irritations, and last several months in the fridge.

What a timely post. Last night my son came to me with something that looks more like you 7 day photos but some did have what I thought was a bite mark but could have been a blister forming. He had about 5 spots on his arms, one on his ankle, and one very big one on his foot. He had helped some friends of ours harvest hay a few days before. I thought something had bit him in his bed but now I think it may have been something in the hay. When I thought it was a bite, I used a charcoal paste on it. The swelling is some better and there still isn’t signs of a blister yet. Just thought I would share the charcoal part in case it would help someone else. Thanks again!

Thanks, Penny. I hope he feels better soon. Charcoal is a good detox agent.

Hi. I know this isn’t a blog for Poison Oak, but many have mentioned it here. I recently had a big scare regarding the burning of Poison Oak. I deliver mail in rural areas. Every year, when people begin burning, I get VERY nervous! This year, I drove by someone in the brush, burning. Usually, it is 72 hours before I feel the burning and stinging of the rash beginning to come out on my skin after exposure. less than 24 hours later, I felt it. PANIC! I found a doc.x I had copied with these instructions, very different from the over 100 pages of P.O. remedies:

“Bringing down the inflammation

Even so, there’s more to healing the poison ivy rash than just eliminating the itch. To bring down the inflammation from the inside, it’s important for one to eat the powdered roots of burdock (1tsp.), turmeric (2T), and ginger (1T), up to three times a day.”

“It’s equally important for one to submerge the affected areas in an infusion of water mixed with oatmeal, apple cider vinegar, activated charcoal, and various essential oils like tea tree and frankincense. Taking baths in this mixture helps. If the poison has invaded one’s face or eyes, it’s safe for one to dunk their face into a sink that is full of these ingredients several times throughout the day.”

“Drawing the poison out and disinfecting the area

After soaking the affected area in these anti-inflammatory and soothing treatments, one should use a skin-drawing and pore cleansing clay mixture to pull poisons and toxins from the skin. This skin mask, which includes bentonite clay, activated charcoal, turmeric, and red Moroccan clay, is powerful, especially when used with tea tree essential oil and water to make the clay into a paste. After allowing this mixture to dry on the skin for 30 minutes, the poisons are drawn out. At this point one can disinfect the area by washing with soap and water.”

I immediately began the internal drink, taking it three times a day, and made a mask of turmeric, redmond clay, (bentonite clay), activated charcoal, Apple cider vinegar, oatmeal ground fine, a drop each of tea tree and frankincense essential oils, and a tiny bit of water to make a paste. I used the mask three times at the first sign of the burning and stinging. I only got one tiny blister on the bottom of one eyelid! The face and scalp did have “phantom” itching, and still do days later, but no sign of the weeping oozing blisters for a minimum of 7-10 days!

There has NEVER, and I do mean NEVER been anything that has helped me with Poison oak, until this. leave the mask on for at least 30 minutes, then rinse with cool water, making sure not to rub too hard, or at all. This WORKS! The clays and Activated charcoal and turmeric draw out the toxic oils, and the ACV and E.O’s help with the antibacterial aspect. Oatmeal is soothing for skin irritations.

I bet it would also work on this type of ‘burn’.

Wow! How awful. Thanks for sharing your experience and the remedies that you used. It could save someone a lot of misery.

I want to see a picture of the plant that caused this. Thanks

All the plants in the carrot family can cause this, such as:

Carrots

Parsnips

Celery

And parsley

Are Angelica and Lovage in the same family? Their appearance is similar to parsley and they get very large, though not as large as Giant Hogweed. Thought I have never had a reaction to any of the herbs in this family besides cow parsnip, I have never tangled with Giant Hogweed. I do eat a lot of celery leaf, celery stalk and parsley and love the scent of angelica stalks. I wonder if the edible cousins in this family might tend to de-sensitize us?

Yes, same family “Angelica archangelica, commonly known as garden angelica, Holy Ghost, wild celery, and Norwegian angelica, is a biennial plant from the Apiaceae family” and “Lovage, Levisticum officinale, is a tall perennial plant, the sole species in the genus Levisticum in the family Apiaceae, subfamily Apioideae, tribe Apieae.”

I eat a lot of carrots, parsley and celery, but under the right (or wrong) conditions, I still ran into trouble.

That looks almost exactly like what my daughter and I get when exposed to gluten. I had it on my elbows and off for years and did not really know what it was. My daughter had hers on her knees and the dermatoligist decided it needed to be biopsied because he had tried everything he could think of. It came back as celiacs! That is not a pleasant rash, itches like crazy!! I may try your salve. I’m all about natural remedies!!

Did you see the psoriasis series? Unrelated to this (I think), my skin went nuts last year. Turned out to be a combination of psoriasis and candida overgrowth. I didn’t test positive for celiac, but am eating gluten free and adjusting my diet in other ways, and it has made a huge difference.

First post in the series – https://commonsensehome.com/psoriasis-the-year-my-face-exploded/

I have a terrible rash, it started as a spot on my waist, i thought maybe a spider bit me while I was gardening. Then a rash developed and started to spread.

The first doc thought impetego, gave me medicine. The rash got worse. Second doc said hives, a reaction to something my skin came in contact with, gave me benadryl and hydrocortisone..and something to supress my immune system. The rash is spreading all over in little new eruptions on legs and arms and neck…the original one is all over my torso a solid block and my skin feels like leather there. Third doc thinks a reaction to a plant.

I’m not sure if I’m making it worse with epsom salt baths but it relieves the pain for a short while.

It looks like the wild parsnip burn but maybe it is infected or something. I am in Eastern Ontario, and the doctors here don’t seem to be familiar with this rash or have any good information on how to treat it.

There’s no way I can safely diagnose over the internet. If it was parsnip or other topical exposure, the wounds should have healed over time, not spread. Have they checked for Lyme’s diesease? I’ve heard of rashes associated with that. Another possibility might be candida overgrowth. For many months last year and into the first part of this year, I battled what looked like a weird rash. You can see some photos of my midsection here – https://commonsensehome.com/psoriatic-skin-causes/, and there are links to other post in the series. My skin has gone through a lot in these past couple of years, but thankfully I’m doing much better now.

You may also want to be checked by a dermatologist to see if you have psoriasis. This sounds very similar to my own experience. It started out as small blisters and red/rough spots, and spread like a rash. After a couple of musdiagnoses, a dermatologist finally identified it as guttate psoriasis. Weirdly enough, my brother, who lives 600 miles away from me, developed the same condition 3 months after I did.

Hello Laurie, This is the second time I have broken out in this rash since moving into a new area of Ontario. Both times I was working outside thankfully with gloves on but exposed arms on a hot sunny day. The first time with the rash it took a month to heal and the doctors didn’t know what it was but now I know… I have the red spots which at first look like mosquito bites since they are itchy but then they develop the puss filled blisters and intensely itchy!!! The thing that puzzles me is as each day goes by I seem to develop small itchy spots which get bigger and turn into small blisters compared to the first ones that showed up. The whole rash is hot to touch and feels so much better when cold compresses applied. I find it hard to sleep since anything coming into contact with the rash makes it more ITCHY….. Think I will try the salve you recommend, does it help with the itch??

Yes, the salve helps with the itch, especially of you include plantain.

Last week I believe I was exposed to wild comfrey. Although the exposure was an indirect exposure (from the fur of my neighbours dog) I received a burn like I never had in my life. I have blisters 1/4 inch high oozing liquids and then crusting up. I washed the area 5 times with soap and baking soda when it first appeared , it doubled in size a day later. I tried jewel weed, It doubles in size again a day later. The arm finally crusted up in 3/8 inch thick crystalline type scabs. Every time I moved my wrist the scabs would crack and the oozing would start again. I am an outdoors man and think of my self as hardened but this thing was starting to unnerve me. ( days later I went to see my doctor who said it was a classic parsnip burn and not a meat eating disease. I was relieved to hear this. She also told me that the wound was infected and that I needed to go on anti biotics to help heal it from the inside. The wound is now an are of 10 x 4 inches but the swelling has subsided and it appears to be healing . Day 2 on anti biotics and the scabs have fallen off but I am getting itchy all over my body. Even the slightest exposure to direct sunlight on the actual old wound starts the tiny blisters again which go away after a few hours in the dark. I will be a lot more careful of touching neighbours dogs in the future. I know what wild parsnip looks like and am not afraid of it, it the mysterious 2 nd hand exposures that keep me on my toes. Wolf from Ontario

Wow – that’s nasty. The secondary infection would keep the wounds from healing properly, too. Good thing you got it checked, and glad that you are on the mend. I hadn’t even considered secondary exposure, but that makes sense.

Just out of question, is this stuff contagious to other people? i have some on my right arm after hacking away at some (blissfully unaware to what it was). if the blisters open, does the liquid spread the infection? can it infect other people?

In my experience, it has not been readily transmitted to others. That said, if one were in prolonged intimate contact, say for some reason you decided to rub the affected limb against someone for 10 minutes while doing the horizontal mambo, there *might* be a slight risk of transmission, but I think the odds are slim to none. A) The burn/blisters show up after the sap has been absorbed by the skin and the skin is exposed to the sun. The pus is the blisters is filled with plasma, not sap, so even if you were to rub your blisters on someone, any sap concentration should be miniscule. B) These blisters hurt! I can’t imagine wanting to maintain extended contact with anything or anyone if you could avoid it.

I came in contact with wild parsnip and went home and caked and washed with soap do you think this got it off in time. The sun was not out when I came in contact with the plant. Please let me know.

There’s no way to tell until the time has passed. Hopefully you’ll be okay.

Wow, thanks so much for sharing. I have had many run-ins wih poison ivy, and then a number of other times where I’m not sure what caused a rash. I have fig trees, so that could be it. I’m going to start growing comfrey – sounds like a good thing for me to have.

That might be it. Other readers have reported fig tree reactions, too.

I read so many articles about Comfrey…being used by doctors in the war for wounded men and so when visas a itty bitty tiny plant with the name tag “Comfort” in it I grabbed it excitedly and said you are coming home with me….lol. Well after giving it a special place in the flower bed with a picket fence around it I let it grow. A few years went by and it grew to three feet tall and three feet around but I hadn’t used it for anything but had been ranting to everyone about how great it was supposed to be. Well we went to a friends and stayed over night in their basement guestroom and my husband felt a sharp prick on his leg and this turned into a inflamed deep open hole the size of a nickel which refused to heal over the next 4th months causing much agony…I finally convinced him to see a doctor and the dr. Was alarmed that his blood pressure was 238/132 and said forget about your leg we need to get this blood pressure down. Well of course his body was trying to fix the leg… I was so upset and when we got home I grabbed three big leaves off the comfort plant and poured boiling water over top and let it sit until cool enough to handle and placed them over top the wounded leg and wrapped with a white cotton cloth and thought we would try this for a few weeks. We went to bed and in the morning to our great amazement when he removed the cloth the hole was closed up abd no longer inflamed. He shouted my name for me to come and look as we both could not believe our eyes. To this day I cannot believe that I had this wonderful miracle working herb growing beside my house and it took me that long to realize or even think to use it..lesson learned. I just wanted to share this and thank you fir the recipe so I can carry it with us and have it for easier use.

The main thing to watch for with comfrey is that it aids healing so much that there have been incidences where a deep wound healed at the surface and trapped the infection inside.

I found this interesting, I’m sorry for your discomfort but a big thanks for sharing with us. Where would I get comfrey?

The life of a blogger – sunburn = write a post on sunburn remedies, parsnip burn = write a post on parsnip burn, got the flu = write a post on home remedies for the flu. 😉

Mountain Rose Herbs (mentioned in the post) stocks good quality dried herbs, or you may be able to grow it yourself.

Thanks so much for the information! We couldn’t figure out how the heck we caught poison oak in the back yard by the fig tree! *laughing* Now I know it wasn’t the ‘wretched poison oaks’ (my son’s name for the rash) *snert giggle snert* but ‘the wretched PPD’ instead!

Have a day filled with love joy and laughter!

Gina

Twas likely the wretched fig tree instead. 😉