Harvesting Rose Hips for Food and Medicinal Uses

This post may contain affiliate links. Read my full disclosure here.

Several years ago, we planted about half a dozen rose bushes as part of our homestead permaculture plan. This year, the plants are loaded with fruit, so I’m sharing tips for harvesting rose hips and how to use them. They’re a great natural source of vitamin C, polyphenols, and anthocyanins.

The hips have tiny hairs that can cause irritation if you don’t process them correctly, so prep wisely!

What are rose hips?

Rose hips are the seed pods or fruit of rose plants that form after the rose petals fall. They’re in the same family as apples, but you have a lot more seeds and less fruit in a rose hip.

If you deadhead your roses to get more flowers, you’re cutting off what forms the hip. Many modern hybrids produce small hips, instead putting their energy into the flower show.

What are the best varieties of roses for hips?

Rugosa roses are known for their large hips. (Our roses are rugosa types.) They form a large ornamental shrub suitable for hedgerows and naturalized plantings.

Samuel Thayer recommends the dog rose, rosa canina, as his favorite source of hips.

He says, “They are incredibly delicious, with a tang a bit like a dried tomato crossed with a raspberry, but with it’s own floral element”. (He discusses wild roses in his book, Incredible Wild Edibles.)

The flavor of our rugosa hips is mildly citrusy, with a hint of melon and floral notes. They have more flesh than most hips, making them easier to use for puree or other culinary uses.

Wild roses and heirloom roses often have sizable rose hips, too. All rose hips are edible, but avoid using any hips that have been treated with pesticides.

When should you pick rose hips?

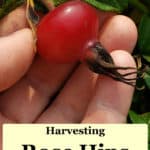

The best time for harvesting rose hips is in fall, after a light frost. Frost brings out the sweetness in the hips, but you want to avoid hard frost, which cause the hips to spoil.

I’ve noticed that some of the hips ripen earlier and start to soften, so I pick them as needed to keep them from spoiling. Some hips get dark red, some stay more orange – it depends on the plant.

Harvesting Rose Hips

Harvesting rose hips is one of the easier fall chores, but processing them to make them safe to eat takes a bit of time.

To harvest, simply pull or snip the hips off the plant. Our rugosas have sturdy stems, so I used my flower cutting sheers. If you’re picking later in the season and the stems are brittle, they may simply snap off.

Processing and Drying

You’ll notice as you handle the rose hips that some are smooth, but others have a small amount of fine thorns. The stems and blossom end are also thorny.

The thorns aren’t the riskiest part of the hips – it’s the fine hairs around the seeds. These hairs can irritate your throat (and your bottom), so it’s best to avoid eating them.

You have two options to do this – keep the hips whole, so the hairs stay inside the hip, or clean the hip and remove the seeds and hairs.

Since we had fairy large fruit, we opted to clean the seeds and hairs out of the hips. We gave them all a good rinse with cool water and got cleaning.

Start by cutting or pulling off the stem and bud ends. Cut the rose hip in half, and use a small measuring spoon to scoop out the seeds and hairs. Dunc demonstrates in the rose hip jelly article.

Would you like to save this?

This takes a LOT of time, and it’s difficult to remove all the hairs. I ate one of the halves we cleaned, and still ended up with a bit of mouth irritation.

Next time we’re gathering pulp, I think we’ll clip off the stems and buds, cook down the rose hips in a stainless steel pot with some water, and strain.

This time, I mashed the cleaned hips with a potato masher as they were cooking with water, and used them to make rose hip jelly.

Note: Our chickens LOVED the rose hip seeds we cleaned from our rugosa roses. Like wild birds, they don’t seem bothered by the hairs.

Drying for Tea

To prep dried rose hips for tea, remove the stems and buds. Keep the rose hip intact for smaller hips, and slice and remove seeds from the larger hips.

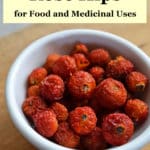

Spread the hips in a single layer in a commercial dehydrator. Dry at around 110F (33C) until completely dry. Let the hips cool and store in a paper bag in a dry location for about a week. (This gives the whole fruit time to dry out equally.)

Run the dried hips through a food processor until roughly chopped. Sift through a mesh strainer to remove the hairs.

Store the hips in a tightly sealed container in a cool, dark location. Date and label, and use within a year for best quality.

Alternatively, you can leave small hips intact and make your tea with the whole hips. Chopped hips will infuse more quickly.

To make tea, place 4 to 8 fresh or dried rosehips in a mug and cover with boiling water. Steep for 10 to 15 minutes, then strain and drink. If using chopped hips, use about a tablespoon of hips.

Benefits

Rose hips are a natural source of vitamin C, polyphenols, and anthocyanins. Raw or lightly cooked hips have the highest amount of vitamin C, but the processed fruit still contains a fair amount.

One study published in the British Medical Journal looked at vitamin C levels in rose hip syrup. They found that after the initial loss of roughly 15%, vitamin C levels in the syrup stabilized during storage in an airtight container.

The study, “Therapeutic Applications of Rose Hips from Different Rosa Species” notes that rose hips have been used to treat many issues, including:

- skin disorders

- diarrhea

- inflammation

- arthritis

- diabetes

- obesity

- cancer

It’s not just their vitamin C, but many other phytochemicals and bioactive compounds. The amounts of these compounds vary with species and growing conditions.

I’m glad we’ve added them to our yard, and look forward to using them for many years to come.

Do you have a favorite rose hip recipe or question about harvesting rose hips? Leave a comment and share your thoughts.

More Herbal Goodness

Check out the Herbs and Wildcrafting page for a full list of our herbal medicine and foraging articles, including:

Sage Benefits – One Herb, Many Uses

Stinging Nettle – One of Most Useful Wild Plants – Weekly Weeder #16

How to Make Elderberry Syrup from Fresh or Dried Berries

This article is written by Laurie Neverman. Laurie and her family have 35 acres in northeast Wisconsin where they grow dozens of varieties of fruiting trees, shrubs, brambles, and vines, along with an extensive annual garden. Along with her passion for growing nutrient dense food, she also enjoys ancient history, adorable ducks, and lifelong learning.

Last updated in 2023.

I saw a recipe years ago in a cookbook that was about a hundred years old. it called for picking the seeds out of whole rose hips then stuffing the hip with raisins. The hips were then cooked in a thick sugar syrup and canned. Two to four hips were served with a little cream as a dessert.

That’s a recipe made with love and patience. So many of the old recipes call for techniques that modern cooks would never even consider.

Hi, all my rose hips turn brown and never turn red. Are all my roses not the right kind to produce red hips? I don’t use pesticides or herbicides.

It’s possible that the variety of rose that you have doesn’t set red hips. Some varieties are more orange or golden yellow. Moisture may also play a role. If conditions are dry, the hips may progress from green to brown more quickly. Some pests and diseases can influence the hip condition, too.

As mentioned in the article, rugosa roses and dog roses have some of the nicest hips. Others types may be hit or miss.

When do i take the fruit from the bush?

There seems to be a couple of stages. 1. The squishy soft thin-skinned and dark fruit that pull off easily (normaly leaving a bit of the hip with the bush)

2. Soft fruit, still bright in colour with a dark stem that can be snapped off with an audible snap with the fingers.

3. Hard fruit, fright red and need to be snipped.

Which is the best to harvest?

Iv just harvested all 3 and also iv harvested entire branches full and ill keep them on the branch.

also stems with three fruits, cutting just past the last thorn, and i leave them on the stem.

Im still not clear on the best way of processing?

Thanks in advance

What do you want to do with your rose hips?

If you want to use them for jelly, use the soft fruits. Clean them, cook them, and strain them.

If you want dried fruits for tea and other herbal uses, harvest at any stage, clean and dry completely. It’s up to you whether you prefer to cut up the hips or dry them whole. They dry more quickly if cut open.

Ok thanks

Yeah mainly jelly at the moment

Does the vitamin C get damaged or lost when boiled for tea? What is the best way to preserve the vitamin C?

To get the highest amount of vitamin C, you’d need to juice the raw hips and freeze the juice/puree, but that’s not the most practical option.

The vitamin C is reduced by heat, but still substantial. I’m going to update the article with some more information on relative amounts of vitamin C before and after heating.

thanks for sharing.

This is amazing

We love rose hips and I make a lot of things using them, besides the rose hims jam. Our favorite is rose hips vinegar which we enjoy over the winter in salad dressings. I also make rose hips muffins in late summer and fall, just using my regular berry muffin recipe but using the rose hips pulp. Rose hip seed oil is used in most skin care products. I just soak the hips seeds in a neutral oil for a couple of months, then strain. Or sometimes I crush the seeds and soak them in the oil and of course strain well. All of these require separating the hairs and seeds from the pulp. I wear surgical gloves as your hands become really sticky doing this job.

That all sounds good. As our rose patches grow I look forward to experimenting with more recipes.

My neighbor gave me cuttings of a rose bush that needed digging up several years ago.

We have gotten a lot more rain in the last two Summers, and today, not half an hour before I saw your article on rosehips, I spotted the first big, juicy looking rosehip this bush has ever produced.

The bush is still blooming and I am hoping for a few more before Fall sets in. In previous years, all we got were tiny, green little hips that were either eaten or shriveled into tiny, dry little refugees before I spotted them.

Thanks for running this article. Timing, for me, was perfect!

You’re welcome.

If your bush as at all similar to ours, they took a few years to get well established and start producing bigger hips. Early on, as you noted with yours, they were small and not worth harvesting.

I bought two roses this year for hips, hopefully in a few years. I never knew about the hairs! I appreciate this site and the information you share. Thank you!

I had no idea, either, until I started looking into more information. They look like you could potentially pop them right into your mouth – until you open them up. My brother said he’s eaten wild rose hips by chewing them up straight off of the plant, but he also chews his vitamins and fish oil tablets.