Canada and Bull Thistle – Edible from Bud to Root

This post may contain affiliate links. Read my full disclosure here.

Welcome to the Weekly Weeder series. Today’s featured weed is the thistle, i.e. plants of the genus Cirsium. No true thistles are known to be toxic, and they are fairly easy to identify.

There are many thistle species throughout North America (and the rest of the world), but the two common in my yard are Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense) and bull thistle (Cirsium vulgare).

The different species are all edible and have similar uses.

Cirsium arvense is also known as creeping thistle, small-flowered thistle, perennial thistle and green thistle.

Cirsium vulgare is also known as common thistle or spear thistle. (Its spines are quite wicked.)

Range and Identification of Canada Thistle and Bull Thistle

Where do thistles grow?

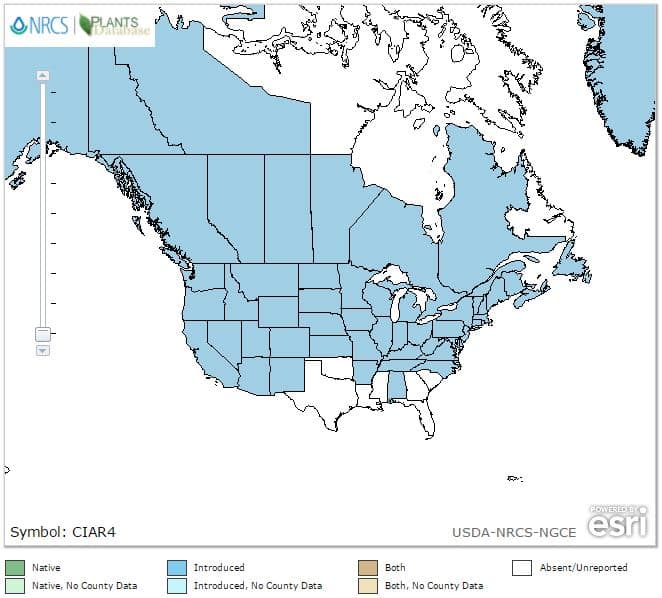

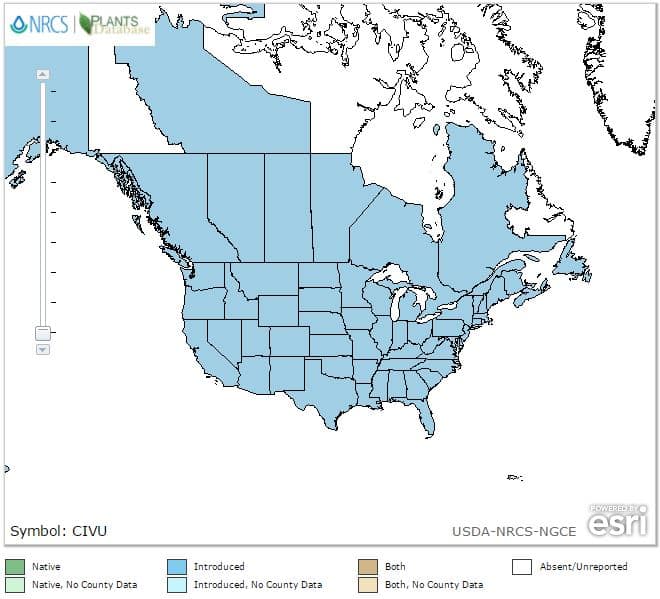

Thistle grows just about everywhere, as you can see from the following USDA range maps. (Adapted from https://plants.usda.gov/.)

Thistles prefer dry ground and disturbed soils with plenty of sun. Their deep tap roots help break up compacted soils.

Although viewed as a noxious weed in many areas, thistles are one of early succession plants featured in The Wild Wisdom of Weeds. Katrina Blair calls them “essential for human survival”.

They may be challenging to work with, but like all things in nature, they serve a purpose.

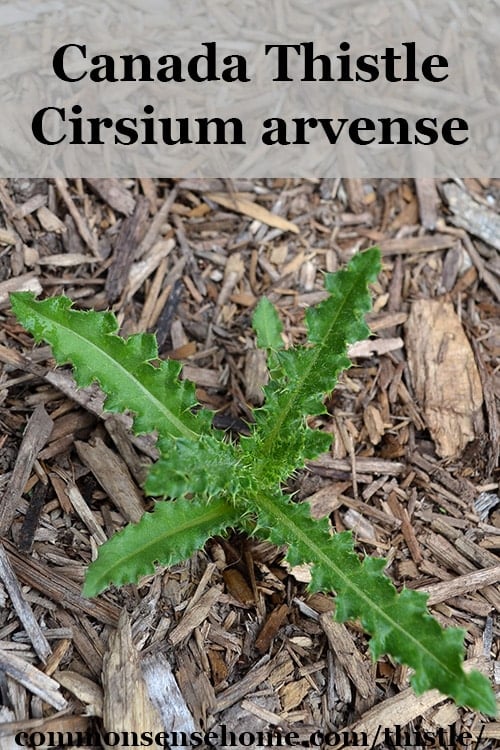

Canada Thistle Identification

Canada thistles (Cirsium arvense) are perennials, growing back each year from their roots.

The plants are 1-3′ tall, and leaves attach in an alternating pattern up the stem. Typical leaf length is 3-4″ inches, although they may reach up to 8″ long and 1″ wide.

Stems may branch near the top. The spines, while pokey, are not nearly as sharp as bull thistle spines.

The leaves themselves have jagged edges tipped by spines, and are smooth on top but often somewhat hair underneath.

Seedlings can pop up anywhere, as only a single seed or a remnant of root is necessary to propagate a whole new plant. The Canada thistle commonly grows in clumps of plants, because it will spread by runners.

Blossoms are a light pink-purple, with many blossoms per plant. Their perfume is quite beautiful.

Cirsium arvense buds and blossoms.

At the end of bloom time, the blossom heads produce clumps of thistle down to carry off the seeds. The photo below was taken when one of our thistle patches was heavy with morning dew.

Bull Thistle Identification

Bull thistles (Cirsium vulgare) are exactly that – bullish. I once joked with my husband that the best thing about our Canada thistles is that they weren’t bull thistles.

(When we first moved here, the place was overrun with thistles. As mentioned earlier, they thrive in disturbed soils.)

Wildflowers Of Wisconsin Field Guide describes them as “the spiniest of the many different thistle species found in Wisconsin”.

Bull thistles are biennials. The first year they start out as low basal rosettes close to the ground. The rosettes can get up to 4′ across.

Leaves are hairy on top and bottom, with a more silvery tone on the underside. The leaves are loped, with each ending in a sharp spine.

In year two, they shoot up a large flower stalk. Mature growth is 2-6′ tall.

Plants bloom in summer with large, reddish purple flower heads that resemble an old time shave cream brush. (See photos below and at top of post.) Plants may have one or more flowers per stem.

Wildlife Uses

Thistle blossoms are much loved by butterflies and other pollinators. We get many European skippers visiting our plants.

Would you like to save this?

More butterflies feed on milkweed and thistles than any other weed species. Painted Lady butterflies prefer thistles as food plants for their larva.

The painted lady is also known as the thistle butterfly. Its scientific name – Vanessa cardui – translates as “butterfly of thistle.”

Many birds enjoy the seeds, especially American goldfinches. Goldfinches also use thistledown to line their nests. The summer and fall bloom time of thistles means that goldfinches raise their young later than most birds.

Herbivores avoid the plants because of the prickles.

Thistles as Food

In The Forager’s Harvest, Samuel Thayer goes into some detail about how thistles were one of the first wild foods he foraged, and how he harvests the center spine of the leaves by peeling off the surrounding spiny leaf material, leaving a stalk like a celery stick.

He describes them and being tender, juicy and delicious. In the interest of science, I found a bull thistle leaf, peeled it and ate it on the spot. It tasted like grass. I was underwhelmed. Still, if I’m in a pinch, at least I know they are safe to eat.

The flowering stalks also can be cleaned and eaten. They are best early in the season, before they are in full bloom. By the time flowers appear, the stalks are hollow and stringy.

The roots, too, are edible, and Thayer says “better than burdock“. I’ve nibbled Canada thistle roots while weeding in the garden. They taste a bit like iceberg lettuce (plus, no thorns).

Roots are dug in fall from first year plants (those with no flower stalk), or during the season as the plants need to be cleared from an area. Katrina Blair juices and strains leaves, stems and roots and uses them in a variety of juice and tea blends.

As a relative of the artichoke, the flower buds are also edible. Thayer describes peeling off outer layers to reveal the heart (and dismisses it as too much work).

The Flower Cookbook describes cooking young buds whole.

The Wild Wisdom of Weeds mentions pulling the pink tops of the flowers and chewing them like gum. (I tried this – very strange, mildly sweet, not at all like gum.)

Medicinal Use

Cirsium arvense can be used medicinally. Red Root Mountain School of Botanical Medicine gives some examples:

This is taken from The Physiomedical Dispensatory by William Cook, M.D., 1869 Medical Herbalism…

Properties and Uses: The roots are slightly demulcent, with stimulating and mildly astringent properties. An ounce simmered in a pint of milk is a family remedy for low forms of diarrhea and dysentery, after the acute symptoms have subsided. Two fluid ounces of such a decoction may be taken every two or three hours.

An infusion is said to expedite labor very effectually, when the nervous system has become fatigued-also anticipating after-pains and flooding. I knew one gentleman to use a syrup of this root in long-standing coughs, where the expectoration was free and the lungs feeble; and he also used a wine tincture in mild leucorrhea and prolapsus.

The leaves made into a decoction and used somewhat freely, are said to increase the flow of milk, and gently to overcome hepatic obstructions; and the juice makes a rather soothing wash (or ointment) for irritable sores, tender eyes, and piles.

In The Wild Wisdom of Weeds, thistle is promoted as a liver tonic, alkalizing food and general tonic for many conditions.

How to Get Rid of Thistles

Like most of my other weeds, I’ve largely made peace with my thistles, too. We allow them to hang out in the wild areas of the yard, and don’t panic when they show up in “barefoot zones”. Regular attention keeps them in check.

Cirsium arvense

To get rid of Canada thistles, it’s best to catch them when they are young and small. When the soil is loose, such as after a rain, it’s fairly easy to pull them and get a long section of root, even barehanded.

Simply grab at the very base of the plant, where it is less spiny, or even just below the soil line.

Their roots are very brittle and break off easily (which allows them to regrow), but with frequent cultivation and mulching they are readily brought under control.

(Barbara Pleasant recommends the same thing in The Gardener’s Weed Book – other than the bare-handed pulling.)

Cirsium vulgare

For bull thistles, I usually use a fork and heavy gloves, unless I can catch them small and get under the rosette. Even then, their tap roots hold quite tightly.

Control of Thistles in Pasture

In Weeds, Control Without Poisons, Charles Walters notes that thistles thrive in soils where manganese is low. Wet springs also tend to bring more seeds out of dormancy.

As a general control, mowing when the plants are in bloom catches them without reserves (all their energy is in the flowers) and knocks back the population.

Cirsium arvense

For more long term control, look at the soil itself. Canada thistles like soil with high iron, low calcium and poor organic matter. Too much nitrogen can make the conditions that favor thistles worse.

Deionized sulfur helps to bring the iron/manganese ratio back into balance. Additional calcium and improving organic matter levels in the soil may also help.

Think managed rotational grazing in pastures instead of simply keeping the herd in one large area.

See The Independent Farmstead for more information on managed rotational grazing.

Recommended Resources:

- The Forager’s Harvest

- The Wild Wisdom of Weeds

- Wildflowers Of Wisconsin

- Weeds, Control Without Poisons

- The Edible Wild

Other Posts You May Enjoy:

- Recommended Wildcrafting Reference Books – Weekly Weeder #1

- Chickweed – Weekly Weeder #2

- Harvesting and Using Dandelion Roots

Originally posted in 2011, updated in 2017.

Great article! Though I don’t think I’ll be eating my thistles. I have a one acre pasture that I would like to cultivate, but the thistles are thick. I will do a soil test and see where we can make some changes there. I had read about buckwheat being good to control thistles, so I may try that also…

Love your blog. What you are doing is an inspiration to me!

Anything that will improve soil structure and nutrient availability will improve the odds of other plants versus the thistles, so cover crops like buckwheat would definitely fall into that category. The thistles don’t taste bad. To me it’s just a lot of work to get to the edible bits.