What You Need to Know About Masonry Heaters for Radiant Heat

This post may contain affiliate links. Read my full disclosure here.

Masonry heaters store heat from wood, gas or electricity in brick, concrete, ceramics or stone, and releases the stored heat via radiant heat transfer over time. Our unit burns at over 1500°F, but the flue gases that go up the chimney are only around 300-350°F. That heat is absorbed by the thermal mass of the masonry stove, and then transferred to the house – not up the chimney.

This is an ancient heating technique used for thousands if not tens of thousands of years. Masonry heaters were used long before the Romans, with some underground and cave masonry heaters dating back well over 5000 years.

Masonry heaters include masonry stoves or masonry ovens and even the modern cousin the rocket mass heater. Larger masonry heaters can have benches or seats built into them. Some also include a baking oven or even a full cooking stove. We will focus on wood fired masonry heaters, but most of the concepts apply to other heat sources.

Masonry heaters tend to be large and heavy. The larger the weight/size (mass) the more heat it can store. It will weigh 1760 to 3000 lbs (750 to 1300 kg) or even larger.

Passive solar heat and masonry heaters are a good match. Even when there isn’t a fire, a masonry stove acts as thermal mass. If it gets up to temperature from any heat source – sun, geothermal, gas, wood or even electric heat – it will then radiate that heat back into the home. This extra thermal mass stabilizes the homes interior temperature.

Fast & Slow Masonry Heaters

There are basically two types of masonry heaters, fast and slow.

Fast burn wood fired or gas masonry heaters are normally fired 2 to 3 times a day. They burn very hot and fast, and then are allowed to go out. The heat soaks into the masonry, and is slowly released from the mass over the course of the day. Fast burn masonry heaters are more efficient, because the higher combustion temperatures use more of the fuel and burn the gasses. Most masonry stoves and masonry ovens sold today are fast burn systems.

Slow burn or constant burn or steady burn masonry heaters burn a small amount all, or most of the day. Traditional masonry heaters are fired or heated regularly throughout the day. These are generally less efficient.

Air for the Fire

A fire requires oxygen for combustion. Feed more air to the fire and it will burn hotter, faster and more efficiently. (Think about bellows feeding the fire of a forge.) Our masonry stove has a dedicated fresh air feed from the exterior of the home to the front of primary combustion chamber. This avoids sending warm interior air up the chimney. When we’re ready to burn, we open the chimney flue PLUS the fresh air feed. When the burn is complete, we close the chimney and fresh air feed, trapping the heat in the masonry. Some masonry heaters meet strict California emissions requirements, because they burn super hot and therefore are very efficient.

Modern Masonry Stoves

Some of the vendors include:

- http://www.tulikivi.com/

- http://www.tempcast.com/

- http://www.greenstoneheat.com/

- http://masonryheater.com/

- https://mainewoodheat.com/masonry-heaters/

Masonry Heater Materials

All fast burn masonry heating systems must be made of materials that tolerate extremely high heat. A fast burn masonry heater will get very hot. (Our TempCast unit is designed to operate at 1500°F or higher.) Most prebuilt systems use refractory cement (stable up to 3000°F (1650°C)) or “high duty” fire-brick which can handle up to 2750°F (1500°C). In comparison, a normal fireplace only gets 700°F to 800°F. We have melted some low grade nails in our masonry fireplace because it gets so hot, and the iron grill in the burn chamber needed to be replaced, as it cracked from the heat.

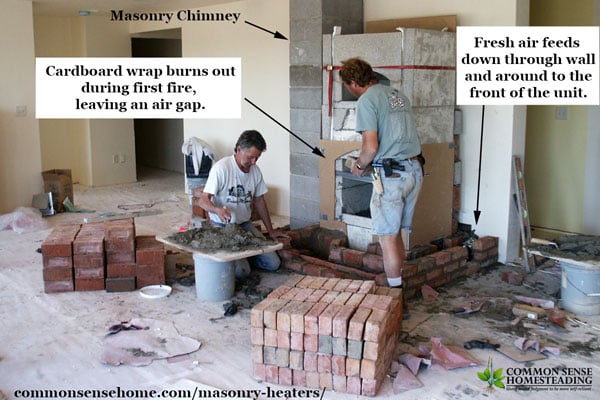

Masonry heaters have extra mass using stone or brick outside the fire safe masonry or refractory cement. In our fast burn Masonry Heater (Masonry Stove) the vendor specified a layer of cardboard between the refractory cement core and the brick exterior. This cardboard burned out during the first fire, leaving a thin air gap between the interior and exterior materials. The gap is necessary because the refractory cement will expand and contract at a different rate than standard brick. Note: Some stone is not safe at high temperatures, be sure you are using stone that is appropriate for high temperature use.

Building a Masonry Heater

Before building a masonry heater, confirm local building codes, permits and other requirements. Select a contractor with experience building masonry heaters. The extra weight and mass of a masonry heater may require special footings and other construction considerations.

Our TempCast unit has a bake oven built into the secondary combustion chamber where the gases are burned. There is ash buildup in this chamber. This makes any baking or cooking extremely messy. If you want to have a bake oven in your masonry heater, I wouldn’t have it as part of the primary combustion chambers.

We also don’t have a very wide seat around the masonry stove. Were we to build again or modify the existing unit, I’d prefer additional seating.

Locating a Masonry Heater in Your Home

A masonry heater is normally placed in the center of a home away from an exterior wall of a building. This allows all the heat from the masonry heater to radiate into the home (none radiates outside). Our masonry stove is roughly in the center of our home.

Would you like to save this?

A masonry chimney for a masonry heater can also be used to store heat from the fire. It absorbs heat from the exhaust and then releases it back into the home, much like the main portion of the masonry heater. Many masonry heater kits include extra flues to direct air flow past extra brick. The heat from the exhaust is absorbed as it flows past more the brick, for instance, with a flue going through a bench seat. A zigzag flue pattern is sometimes used to increase heat transfer.

What is the difference between a Masonry Heater and “Normal” heaters?

A normal whole home heating system uses propane, natural gas, wood, electricity or even geothermal heat transfer to heat air or water/antifreeze mix. The warm air or liquid warms the home (convection heating). A masonry heater dumps heat to the mass of the heater, which slowly radiates the heat to the rest of the home, and feels warm to the touch (radiant and conduction heating).

Forced air heating blows warm air around the house. Because hot air rises, forced air systems tend to be inefficient, but are fast, inexpensive and allow for heating and cooling in the same forced air system. Some forced air systems use geothermal for both heating and cooling. In larger buildings, forced air systems also provide fresh air throughout the building.

Hydronic heating can be a radiator system or in floor radiant system. Modern systems use a heat exchanger in a boiler or even in a dual purpose hot water system such as a Combicor water heater. Nearly all modern system use a water and propylene glycol mix to deliver the heat. Radiant heated flooring/tile and or concrete acts as thermal mass and heat distribution system.

When remodeling you could apply masonry heater concepts to a more traditional system. You could run a hydronic system through a large brick, tile or stone mass to act as a heat sink and radiate that heat into your home. Some people create a large brick surround near a conventional wood stove. This is technically not a masonry heater, but the heat from the wood stove to heats the surround, and the surround heats the room.

Pros and Cons of Masonry Heaters

We’ve had our unit for over 12 years now, and overall it’s worked fairly well. That said, there have been some issues.

Cons:

Price – Masonry heaters are labor intensive to install, and the kits and materials are expensive. You could buy several regular wood stoves for the price of one masonry heater.

The wire used to open and close the chimney damper busted after only two years of use. Thankfully, at that time we were still able to contact the original masons who installed the stove, and they retrofitted a sturdier cable than the wire originally included with the TempCast kit. This did require removing a block from the chimney and adding a bigger metal conduit for the cable to move through.

The wood burned in the masonry heater should be very dry and relatively small diameter so it burns quickly. You must have dry wood (generally recommended for most wood stoves), and it needs to be split in most cases.

Pros:

The unit burns hot, but stays safe to the touch. Because our unit is located in a family room, we were concerned about it being bumped into by the boys, especially when they were younger. Most of the unit stays comfortably warm, even when actively burning. The only parts you need to avoid touching are the doors. The rest of the unit radiates a gentle, soothing warmth.

Our masonry stove stays hot long after the fire is done. We typically build one to two fires per day, and the units retains heat for over 24 hours after a burn. In fall and spring when we need to add less heat to the house, the unit is only fired at night, and stays warm until the next night. In winter, it’s fired morning and night, but never cools completely in between.

It burns less wood than a regular wood stove. Because we’re not stoking the fire constantly, we burn less wood.

Would we do it again?

If we ended up building again, would we include a masonry heater? Maybe, maybe not. We love the way the heat slowly radiates out of the masonry, but the cooking option for the TempCast has turned out to be a mess.

A wood burning cook stove with a masonry surround might be a more practical and less expensive option. At the very least, if we did a masonry stove again, we wouldn’t have the bake oven as part of the primary combustion area, and we’d have a bigger seating area to sit and soak up the heat.

Other Green Building posts you may find interesting:

When you state flue temps of 300-350 are those temps measured internally or externally on the pipe? Thanks

Those temperatures are the estimated temperature range of the gases exiting up the flue, provided by the stove manufacturer.

Question for the group: I have a home made masonry heater with a glass door. There is a decorative screen behind the glass to keep wood from falling into the glass. I installed the heater many years ago and am looking to replace the protective decorative metal screen. It measures 12-1/4″ x 10″ and is mounted with a two-pin hinge (top and bottom of the door). Does anyone know where I can get a replacement? It seems my first vendor is out of business.

I’d contact a local company that does chimney cleaning and fireplace maintenance. They should be able to help you out.

I wouldn’t think there would be much to catch and release. After all, it’s supposed to be protecting the wood wall so you wouldn’t want it to get warm. I’m guessing there is a air gap between the two so you have a constant airflow taking the heat energy from the slate as it’s being absorbed. The setup is really not intended to store energy for slow release later. Cast iron stoves dump their energy into the room quickly. Masonry heaters are designed to release the energy slowly so as not to overheat the space. They also burn more efficiently so there is less smoke and more BTU’s harvested from the wood. Downside is they are pricey and are slow to respond if you are starting from cold.

I’m looking into building a masonry heater in the future, so I appreciate the thorough writeup.

I have a nice big cook stove that heats my kitchen all winter (we heat only with wood), with a roofing slate panel behind it to protect the wood wall. Even when the stove is running hard (baking a pie or roasting, etc ) the slate barely heats up. I imagine this is because the stoves cast iron really absorbs the heat and radiates it thru the cooktop and oven. The flue gas temp is not high, either.

I say this just as a response to your comment about having a cook stove with a masonry wall for radiating excess heat. Maybe it depends on the stove, but for me there isn’t much to catch and radiate later

Laurie,

Has Patrick gotten your stove ti function now, as it did in the beginning? Did he have suggestions for new Temp-Cast owners so that what happened to yours wouldn’t happen to them? Just curious, we are in MN and thinking of a masonry stove heater for a future cabin…

Hi Kathy.

I talked to Patrick, and he talked to our local stove repair/chimney sweep guy. We need to make arrangements for the sweep and potential repairs. Then next fall we fire it up and see if it works.

Kathy,

What happened to Laurie’s heater can happen to any masonry heater or any building. Laurie said the heater settled “Settling = to move to a lower level and stay there; to drop. The foundation was specifically reinforced to accommodate the weight of the masonry heater, but it still appears to have settled slightly, impacting the efficiency of the burn, as my husband noted.” As it settled, anything attached to it or that it contacts will try to bend or twist it and cause cracks. The heater didn’t settle because of a bad foundation. It settled because the soil underneath was not capable of supporting that much weight. Reinforcing a foundation is done by adding rebar, using stronger cement, making it thicker or any combination thereof. The reinforcement is to prevent foundation cracking. It won’t stop it from sinking if the soil below isn’t up to the task. Some types of soils are more stable than others to build on. If you don’t have capable soil for the project the builder will dig deeper or use pilings to get to solid bedrock. Even if you have a stable soil directly under the foundation you could still have weaker layers or voids below the stable layer. The ground below our feet is not always as solid as we think it is. Builders do their best based on the geology of the area. You could drill a test core close by your building site to give you more assurance or contact a soil engineer.

Actually, odds are I may have been mistaken about the cause of the problem, or at least, it’s only part of the problem.

When talking to Patrick, one of the things we discussed was wood diameter. In the original installation video (which we don’t have anymore because it was VHS and we ditched our VCR) they showed very small diameter fire wood being used – about 1-2 inches diameter. The instructions noted that wood should be below 4 inches in diameter, but smaller was good. People were even heating their homes with rolled up newspapers (so it claimed).

Since my brother-in-law owns a sawmill, we started buying his scrap wood, which is quite small diameter. (He runs mostly stakes and lath.) Patrick suspects that even with the dedicated air feed, using the very small diameter wood needs too much air, and we’re getting incomplete combustion because the stove can’t supply enough. Over time, even with annual cleanings, there’s likely been some build up in the flu, because certain spots are tough to clean. There may also be a small air leak in the back because of settling, causing additional trouble. Our cleaner tried to patch it before, but it’s tough to access because it’s under a stairway and partially covered in drywall.

Once we get the unit cleaned and repaired, Patrick suggested 2-4 inch diameter wood for the bulk of the fire, with some smaller pieces at the top being acceptable to get the fire started. (The burn is designed to be top down.) 4 inch diameter wood should be split, 2-3 inch diameter whole. We’ve started stockpiling larger diameter wood for next winter. My brother-in-law is thinking about retiring soon, so the sawmill scraps won’t be available much longer anyway.

Laurie, Your instructions are different than what I have. Mine is a model 2000 corner unit purchased in 2014 and the manual says “Split all cordwood (regardless of size) and all pieces thicker than 5 inches in diameter.” I checked the Tempcast website and they only have the planning guide and assembly manual available to download. Don’t know what the current owners manual says. The larger pieces do slow the fire down as they don’t have as much exposed surface area compared to a pile of many smaller pieces. I have a 5″ plywood circle that I use when splitting. If the ends fit in the circle it’s good to go. Split any cordwood over 3″. Splitting the ones less than 3″ is a challenge. Small target to hit and they don’t stand on end easily. Hoping that larger pieces solves your problem.

Our unit was installed in 2005, so a lot has changed in the intervening years, I’m sure. We’ll see how it goes.

Hello Laurie,

My name is Patrick Sieben and I am the new owner of Temp-Cast Masonry Heaters. I am also a Certified Heater Mason with the Masonry Heater Association of North America, and its current sitting secretary. I bought Temp-Cast a year and a half ago from the former owner. I am sorry to hear about your troubles and would personally be willing to help you resolve them. I know that what you’re expressing is an anomaly from what I have heard from thousands of happy customers. As to your previous customer service issues, I can understand this as well and am willing to speak more to it if you would like to chat. Please reach out to me if you are interested.

Patrick Sieben

Temp-Cast LLC

(651) 303-9841

patrick@tempcast.com

https://tempcast.com

I will take you up on that offer. I’d love to get the stove functioning like it did the first couple of years.

keep us up to date like this. Thanks for sharing.

How would I go about finding a chimney sweep to clean a masonry heater? What questions should I ask to tell if they know what to do? I live in Virginia where these types of systems are not common. Any advice would be appreciated.

A good quality sweep should be able to clean one, even if they haven’t worked on one before. I’d ask if they have any experience with cleaning a masonry stove, how much experience they have in sweeping, are they bonded and insured, and do they have customers that are willing to recommend them.

Any system if not properly installed will have problems. Something as simple as chimney flashing, if done incorrectly, will leak, but that doesn’t mean that the concept of “flash / counter-flash” chimney flashing as a system is bad.

I’ve seen many shapes and sizes and designs of masonry heaters. Some work better than others. Some are absolute junk. One poor specimen does not condemn a whole class of units.

A Statement like “wood heat is….” is simply too broad to be meaningful, and one particular unit functioning poorly does not negate the efficacy of a “system.”

I have never heard of a failure of this type before.

Are the mixed results earthship type dwellings (proven repeatedly to be a flawed design)? Most passive solar does not work well due to lack of storage flow, which leads to overheating in summer and lack of heat in winter. Passive annual storage is site specific and requires a lot of attention to detail to get it right, but can work well even up in Canada and Alaska where winter sun is practically nonexistent in many places. But if people confuse what they’re doing with the design of earthship or earth sheltered, it won’t function properly.

It’s been a number of years, but the one I remember most was a more conventional style home with large sand bed storage under the home, not an earth ship. The couple who lived in the home noted that it sometimes got quite warm in fall, and while passive winter temps stayed in the 50s from solar, that’s not a comfortable living temp for most people. They were snowbirds, so they were okay with it as long as the house didn’t freeze while they were gone.

That’s one (very basic) type of passive solar system that’s been tried, but not the same thing as passive annual heat storage with an umbrella system and earth tubes.

The sand bed storage needs layers of pex throughout, 6” spacing horizontal and vertical, with circulation from solar panels on the roof all summer and then switch to flowing through radiators in winter. A PV panel can power the pump in the summer but requires power in the winter. You have to either super insulate the sand pit from the surrounding earth (probably easier) or include the earth and create an umbrella system. In either case you also need to insulate between the sand bed and the house, so as not to gain heat in summer when you don’t want it.

How much does something like that cost (thinking about all the earth moving involved), and who’s doing it? I know any builder around here would likely think a person was nuts to even propose it.

The insulated sand bed would involve a day of excavation, sand (cheap), insulation and pex for that part, a day to construct/layer/fill, then the piping and pump for the solar. I’m guessing maybe half what you paid just for the kit of your heater. Definitely cheaper than what a full basement costs to build. As far as the umbrella system, it’s site specific so a lot depends on the lay of the land.

In this climate, I would think that you would have to keep that sand bone-dry or the water flow through it would rob all the heat very quickly. If so, now you have what is basically a deep, super-insulated (on all six sides) basement, largely reliant on perfect waterproofing that lasts forever without the ability to do maintenance, coupled with solar heat cells on the roof, piping, fittings, pumps, etc, all with a limited lifespan, maintenance needs, etc….

One of the things I like the most about wood heat is it’s already sustainable, there’s minimal maintenance, no electricity needed, and it’s inspectable/serviceable. It’s not really a fair comparison because they have different design assumptions, but if the heat stored turned out to be less than was needed, you’d be going installing an additional heat source anyway. For the cost of rigid foam insulation installed underground, you could double up the blown in or batt insulation in the house several times over. Houses are pretty heavy, their contents are pretty heavy, and if the contents include a masonry heater, tile floors, etc. they are heavier still; it may not be as much mass as a sand pit, but it might be of similar magnitude and is a better use of limited resources IMO.

Im not sure what the connection between climate and water flow is, but with an insulated rigid box, actual water *flow* should not be an issue. If it is, you’d have problems with any foundation, so that’s a drainage problem that needs to be addressed regardless. And wet sand would make a far more efficient mass than dry, so that’s not a bad thing at all, nor are you reliant on waterproofing. Maintenance cannot be done to the tubing in heated slabs, either. No difference. The cost of tubing, pump and rooftop collector is minimal, maintenance is easy when needed. The heat storage can be calculated, same as with the mass heater. The sand bed does not need wood fed to it daily, and uses no limited resources beyond initial construction, same as the mass heater. Not every house can double up on insulation, and the weak link is usually windows when it comes to heat loss. If either system proved to be too small you’d be in the same boat. Conversely, if either proved too large, you’d have a worse problem with the mass heater, since you can’t run it ‘half hot’. The sand circulator is on a thermostat. Energy input is similar- The sandbed has a pump that needs electric power, the wood heat needs human (and wood) power.

To be clear, I’m not advocating for the sand bed system, but it’s been proven as described, in very cold places. I think the umbrella concept is better. Both are site specific, requiring you not live on bedrock or a swamp. I also like mass heaters, but the initial question asked, that I replied to, was about Passive solar. Then Laurie mentioned sand bed, so I addressed that too.

Lastly, despite wood heat being ‘inspectable/serviceable’, ironically here we are, discussing a very expensive wood heat system (tempcast) with a problem that can’t be found/diagnosed. The owner is not entirely happy with it. Thus every system has its own pros and cons.

Hi I wonder if you’ve come across anyone living in an earth/passive solar home that used a masonry heater for heating? We once visited an earth home and the owner told us it maintained a temperature of 55 degrees in our sometimes -40 degree winters. (That way if a family travelled in the winter, they would not have to enlist someone to load wood into their masonry heater so water pipes would not freeze when they were gone?)

I’ve heard about folks doing builds like that, and I suspect our ICF (Insulated Concrete Form) house would hold heat pretty well, but I don’t know anyone personally who has built a home like that.

I do know somebody who has built an earthship-type house and looked into using a masonry heater to warm it. In the end they went another way; with a wood fired boiler. The space was too large (80×30) to heat practically with a masonry heater or rocket mass heater, and there are other issues too. Earth-sheltered building in cold and wet climates is extremely hard to get right. As far as passive solar homes go, if the air is 55F in the depths of winter then I think the masonry heater will work great, depending on the particulars of the site and house design. A passive solar home could be designed so that solar gain was stored in the masonry heater thermal mass, doing double duty as a solar heat battery and heater in one. Any passive solar design is very specific to it’s context so it might even be unnecessary to have a masonry heater at all. If you are serious about looking into passive solar and you live in the north, figure out how much solar energy is available in the winter where you live. Where we live it’s practically zero, it’s cloudy too often. As for keeping the house warm while nobody is in it, if you are going away for the winter, just drain your pipes — it’s not difficult to do.

Thank you, we appreciate the input. This would be a smaller space to heat, but we agree that an earthship is very hard to get right and passive solar not always achievable with cloudy days…we would need to do research and most importantly, find a reputable, experienced builder for those types of homes. It is just so appealing to pay for something up front that would allow living off the grid thereafter…

If you like the idea of passive solar, explore the concept of passive annual heat storage, which would work regardless of winter sun. It’s 100% solar powered, no heater needed, and simply traps the summer heat of the earth near the home.

I’ve seen very mixed results with homes that have tried the concept, at least in our area.

Efficiency numbers can be a little misleading because there’s at least two ways to think about efficiency. There’s combustion efficiency, which most metal stove makers quote, and there’s overally efficiency. The first measures how much of the fuel is converted into heat, the second considers how much heat makes it in to the space. Be mindful that you don’t compare one with the other.

I would say the second number is the only one that matters, and is a byproduct of the first number anyway. How much usable heat is produced, is the efficiency that really counts. You can’t have overall efficiency without combustion efficiency. The problem is, in a test lab you can only measure combustion accurately. Installation will dictate overall results. Then the comparison becomes ‘a cubic foot of dry oak has x BTUs’ so how much does this device burn vs that device in the same home.

http://www.lehmundfeuer.de/

Hi I came across these German websites who have cob based heaters instead of brick. Would these be considered masonry heaters? Contemplating a cozy nook for the winter to lie down with a glass of wine and a book.

I enjoyed reading your experience with masonry heaters. Thank you for the info.

Yes, those are masonry heaters.

What is the highest efficiency you can get from a masonry heater?

It depends on the specific heater. Oregon University did a study of contraflow masonry wood-burning heaters and determined an operating efficiency of 79.5 % .

Thank you for the link. I found this article on radiant heating sobering too.

https://www.resilience.org/stories/2015-03-16/heating-people-not-places-radiant-conductive-heating-systems/

Yep. By default, heating systems that heat air spend a lot of energy inefficiently heating areas that are not used.

I read the Oregon study and found many flaws in it’s methodology. There were so many estimates used and factors not included that it makes the outcome worthless. Here are a few that I found:

1. Moisture content of wood used was not considered.

2. BTUs transferred from the heaters foundation into basement or footing. Yes, heat travels down.

3. Performance of windows and doors….How old are the seals? Are the screens on (block solar gain)? Are there curtains and what color are they? How much actual sunshine did they get during the test?

4. They had some rooms closed off so they just eliminated them. Heat still goes into these rooms.

5. No blower door test. They estimated air exchange rate. This is a huge amount of energy either saved or lost in a building. It also matters where in the envelope the air is being lost. Is it high or low in the envelope. Outdoor wind speed also affects air exchange rate.

6. Occupants entering or leaving. There were four people living it the house during the test. Doors opening, bathroom ventilation, cooking, cooking ventilation, dryer ventilation, etc.

I am not an engineer, or a trained builder. I am building my own house and have learned a great deal in my researching building techniques and energy efficiency. Trying to measure the output of a masonry heater the way they did is nearly impossible to do accurately. They even stated in the conclusion that this study was not very good due to all the estimating:

“Further study of the stove’s efficiency would benefit from testing in a closed environment. The variables of internal heat gain from occupants and appliances and the passive solar heat gain were estimated in this study but could be eliminated entirely in a closed laboratory experiment. ”

I would put zero stock in the 79.5% number. This study is embarrassingly bad. Oregon University should be ashamed for publishing it.

From Temp-cast website:

“Testing in Finland has shown that masonry heaters typically attain combustion efficiencies of 88 to 91%. Independent laboratory testing of the Temp-Cast heater in North America demonstrated a combustion efficiency of 94.4% and heat transfer efficiency of 65.4%.”

Heat transfer efficiency shows how rapidly the heat produced by the fire is transferred to the room.

One thing I found in my time at the Solar Energy Lab down at UW Madison was that making simplifying assumptions to make experiments feasible to run in the lab was quite common. (OU is unlikely to be embarrassed. This is typical.) As such, I tend to take results of said studies with some degree of skepticism – but they had a number, which was what was requested.

Even if they completely nailed the combustion efficiency numbers on the stove, that’s a very small part of the whole picture, as you have pointed out.

Big factors that I found to be virtually ignored at the solar lab were ease of installation, maintenance and durability.

The Temp-Cast wasn’t any more difficult to install than any other masonry based heater, but unfortunately we’ve run into issues with long term performance. I did not expect this. We planned to make a serious investment and have a lifetime stove.

Our chimney guy (who has worked with many different types of stoves and masonry heaters over the years), has plugged leaks and checked everything he could access, and we still can’t resolve the smoky burn issue. Temp-cast has been no help. Our case may be the exception rather than the rule (hopefully), but it’s our experience.

I take it that cleaning the area above the bake oven and side channels didn’t help then…or have you still not given that a try?

Everything has been cleaned as much as possible by a professional sweep, but due to the configuration of the stove, access is limited to some areas.

Jasper (my sweep) suspects an air leak that he can’t locate, likely on the back side of the unit, against the wall. He’s found some leaks and plugged them – the cleaning access port at the base of the chimney, and down low on the back side of the unit where he could see a little of it because it’s unfinished under a set of stairs. We had soot leaking out back there at one point.

Efficiency is a term that can be misunderstood if not placed into context. For example, I have an ultra-high efficiency tankless water heater. It is so thermally efficient that the flue gases will no longer rise on their own out of the stack (not hot enough), so they must be blown with a fan. The byproducts of combustion will no longer be carried away from the unit by steam and smoke; instead they condense into a toxic acidic stew that must be piped away and diluted in order to prevent ecological or structural damage to the home.

While the unit may use little fuel per BTU and is thus thermally efficient, it is not particularly sustainable. Part of the reason I love my masonry heater is because it contains no moving parts and is constructed of ultra durable materials, while also being very thermally efficient. I would not want to add a powered blower or a condensate drain or any other contrivance to it even if this would technically improve one measure of its efficiency; to me it is more important that it is a durable item that will not end up floating in the Pacific Ocean or rusting in a scrap yard, and that will provide a lifetime of trouble-free service; something I suspect will not be true of my ultra efficient hot water heater.

In this way, I feel a masonry heater is an efficient use of embodied energy that creates little waste and requires little maintenance.

Finally, the intensity of fuel processing required to operate a masonry heater can be very low. I fuel my masonry heater with slabwood, a cheap byproduct of lumber milling, which is trucked from the mill directly to my home, only one trip on a truck and zero further processing required, not even hand-splitting. Because slabwood is not desirable as firewood for most people (who want long burn time), the masonry heater is actually putting that waste product to what is arguably it’s highest use, to me this is a very efficient use of the leftovers without the complications of wood pellets or other highly processed fuels.

Thanks, David. We burn scrapwood, too, and wood that doesn’t burn well in conventional wood stoves.

Thanks for the reply. Sorry it’s taken me a while to jump back in here.

A suggestion. Get one of either:

1) Standard cord wood, enough for 2 loads, not split beyond typical wood stove size.

or

2) a package of compressed sawdust briquettes.

I prefer #1.

When using very small fuel the fuel can emit it’s volatile gasses faster than something like a Temp Cast can keep up. While this doesn’t explain the degradation in performance (videos may help, but my guess is that without being there it will be impossible to tell what’s up with that) it may help the combustion.

Is there a way to send photos through this comment window?

Hope this is helpful to you. I’ve been designing and building stoves for a while, and consider myself to be toward the top of the heap in terms of actual knowledge here in the states. I have designed and built from 24″ diameter stoves to 6’x6′ stoves heating from 400 to 3000 square feet. I troubleshoot and help people on a regular basis to fix the many “custom (bad idea)” stoves that were built here in Maine in the 1970s.

The TempCast kept up with the small fuel just fine in the early years, and their manual specifically notes that wood above 4 inches in diameter should not be burned because it decreases performance. We have at times had “normal” firewood, split into hunks that are 4 inches or less in diameter, and there was no improvement in the burn quality.

I appreciate the input, but at this time I think we just need to check the space above the bake oven and the fresh air intake, and replace the gaskets again, and see where we’re at.

I’ve been designing and installing these things for a number of years, from basic to completely custom. I know my way around them.

Always the first place to start is with a moisture meter. Is the wood dry? Maybe you’re already setting it up against the stove for a day or two prior to burning, but if not, that’s a great way to final dry the wood. When I fail to do this, I notice a big change in performance.

After that check your air inlet to make sure it’s not clogged with something.

Is your unit equipped with a bypass damper?

Do you have a photos of the unit showing details you think may be responsible for the issues?

Eric the wood starts out as scrap from stakes. Then travels across state. Then is stored under tarp for a 1/2 to 1 full season and then stored inside for about a week in that location (next to fireplace). The quality of the wood absolutely matters, we agree. We got some wet stuff and it didn’t burn well. We can double check but the chimney/masonry guy checked that also. He did find infiltration (white areas along seams in the refractory cement) and patched what he could get at. My guess is something settled in the back and we are getting a tiny loop (not big enough to kill the fire but enough to cause it to not get hot enough to melt metal. And yes he did a air test on the intake and the entire chimney (and cleaned all just in case). Like I said i am betting if he took it apart he would find something cracked or unsealed in the flue behind through the masonry before it goes up the chimney. I am unsure if we have pictures of the white along the soot line or the inside the clean-outs and areas he could access before and after. There is just an open/closed on feed (exterior) and to the chimney. We open both for the fire and then close both after the fire to hold the heat. We would love if you could take a look 😉 it was FANTASTIC when it still burned hotter. The pizza and baked beans were excellent.

Yes, we’ve tested the wood with a moisture meter. We also noticed a big difference in performance with damp wood early on, and set up a system to ensure that the wood is extremely dry by the time it heads into the masonry heater. We keep two wood racks in rotation, and stack the wood in the racks in alternating layers for good air flow. (I’ve double checked it with a moisture meter, too.)

Our chimney cleaner and I have inspected the unit annually. I’m squeamish about heights, so I don’t go up on the roof with him, but he says he’s seen no signs of deterioration in the chimney. We’ve checked the fresh air intake – no signs of blockage. Damper for fresh air appears to function as it should.

No bypass damper. We have a pull down cord to close off the top of the chimney, and a damper on a switch for the fresh air feed. Both appear to be working as they should be.

A couple years ago, we noticed soot under the stair behind the unit. He plugged that leak. The access port at the base of the chimney was also leaking, so he tightened that up. Visibly inspecting the inside of the stove, you could see leakage spots at joints, and he sealed those up, too.

He’s been in the industry for years, and he’s at a loss for what’s specifically causing the issue. I’d love to be able to point to something and say, “This is the problem”, because then we’d have a chance of fixing it. We must be missing something, but I can’t figure out what.

The fire doesn’t seem to burn quite as intensely in the primary burn chamber or the secondary burn chamber. The first three years, we had more blue flame in the main chamber, and both windows would burn off the soot (primary and secondary combustion chambers). Now, we see less blue flame, and the secondary combustion chamber window (and the chamber itself) are covered in soot.

The only work that’s been done on it other than sealing leaks and annual cleaning was when we had the fresh air intake froze closed during a blizzard. A friend of mine came and took it apart and removed the ice. (August was stuck living two hours away at that point.) We also removed the insulation around that part of the intake so that the house heat would keep it from freezing up again. It looks like it’s working normally, but we haven’t taken it apart since then, or run a camera through the entire length of the fresh air feed. I’m hesitant to take it apart lest I screw things up more – and I don’t have a camera scope.

I was hoping that sealing the various leaks that popped up over time would help (I assume these came from the settling mentioned in the post), but so far, no significant change.

It sounds like you have really been through a lot with your heater, and I’m sorry to hear about that. I hope at some point you figure out what explains the change; it must have a cause because settling really doesn’t explain what you are seeing very well, unless the settling is so severe that the actual structure of the heater is seriously compromised, which would be obvious. Even if the concrete slab had shifted due to the subsurface changing, it’s just not clear how that would lead to poor burning performance; I mean it might not be exactly plumb and level anymore but fire doesn’t care about that. Assuming you have a reinforced concrete slab, even if the slab is cracked it is still all in one piece because the rebar is holding it together. The masonry heater weighs a lot but it’s not going to overwhelm the compressive strength of a concrete slab with reinforcement.

Based on all you have written, the weak point of your system seems to be the exterior air feed. I would investigate that as the most likely point of failure for whatever is happening. It could just be a big mouse nest in there that is compromising your airflow enough to cause the fire to starve for air.

The vent has a mesh grate over it, so not easy access for rodents, but I’m going to talk to the sweep when he comes this spring and see if we can take it all apart to double check.

There’s visible cracking in the floor, but nothing that I would consider severe – unless there’s something going on inside the unit that I can’t see.

Have you tried replacing the door seals (main doors and bake oven)? The Tempcast manual states that the door seals require periodic replacement. Maybe that is where you are drawing excess air. Would explain doors not staying clean and poor burn. My second thought would also be to check the air intake for obstuctions.

The gaskets are checked annually and have been replaced. The air intake has been visually checked from the outside, but we’re going to take the pipe apart this spring and double check.

One last idea… Was your chimney sweep able to clean the area above the bake oven? Kind of a flat area up there that could collect ash and block airflow over time. Not really sure how a sweep could clean that area out as it is not easily accessible. Was thinking you could tape a cellphone set for timed pics on a ruler and try to poke it up there to see how it looks. Also, the bake oven glass does not have an air wash like the lower doors so it will get soot covered quickly. Mine gets covered after 1-2 fires.

No, I don’t believe that he’s been able to access that area, so that is a possibility. In the early years of operation of the heater, the door would soot a little, but you could still see flames flickering through. Now it has about 1/8 inch black coating of soot at all times.

I’m at the pointy end of getting one of these. Reading through all your comments on the sooting issue reminded me of a warning in the manual… it specifically warns to not allow air from underneath the grating into the fire, as it will defeat the wash down the glass from the air intake, and I’m guessing may reduce the burn efficiency because of the less turbulent flow… make sure that area below the grating to the ash drop is airtight.

Yep, we’ve checked there, too.

I would be more suspicious of the firewood quality than look for leaks. Even if a masonry heater core develops a crack, it isn’t as if there is anything behind the crack but another layer of masonry. If something is structurally unsound in the chimney, I’d use a double wall steel flue pipe instead.

On the other hand, even small differences in wood quality can make a huge difference and the firewood business is full of scam artists. If your firewood isn’t checking (cracking radially) on the end grain, or if there is bark that won’t come off the logs easily, your wood is probably too wet to burn well.

We’re burning the same wood we’ve burned from the get go – remnants of hardwood stakes provided by my brother-in-law – which are small diameter and bone dry. They’re about as perfect for burning as we could possibly get. The only thing that’s changed is the stove itself.

Temp Cast is one model. To judge masonry heaters on one model is like judging all cars against one maker, like saying “would I buy a car again? I don’t know… I had a Taurus once and it….”

Be curious what you mean by “settling”?

What do you means by loss of efficiency? This is perplexing.

You are correct. We are not judging ALL masonry heaters, just our installation. And any others we have been exposed to first hand.

Regarding the efficiency, the burn is not has hot as it was originally. The efficiency is a decrease in the combustion of secondary gases. It previously got hot enough that the glass and refactory cement would be fully clear in the primary and secondary burn chambers. We could put a pizza in and not have to worry about soot. That is no longer true. The chimney expert we brought in believes it is leaking (and has patched some) but it is still somehow failing. It appears from the testing, that the combustion is fouled slightly (decreasing temperature). We use the amount of material left over and temperature as our measures of efficiency. Over time it is burning less and more is left over as soot in the well and in the upper chamber. Yes it is perplexing.

Our personal experience is with this unit, but looking at pricing, all masonry heaters are expensive due to the labor component in installation. Materials durable enough to hold up to the temperatures involved are also not cheap. If someone has the skills to do the installation themselves, that would reduce the initial cost – but that’s not the case for us. I’m still on the fence as to whether any masonry heater would have been better than another type of heater for us in this house. Your experience may vary.

Settling = to move to a lower level and stay there; to drop. The foundation was specifically reinforced to accommodate the weight of the masonry heater, but it still appears to have settled slightly, impacting the efficiency of the burn, as my husband noted.

Note I left a reply as a new comment in the wrong place, sorry about that.

The wood to the left of the heater in the pictures, is this a typical fuel load?

A typical fuel load is about 6 layers of 1 inch diameter hard wood stakes 16 inches long, stacked in alternating layers with some newspaper mixed in for quick ignition, lighted from top down per TempCast instructions.

Hi David, I just read your comment about loving your bake oven…how is yours different from Laurie’s with all the mess they get from the soot? Did you install the oven in a different way? Are you far from Minnesota (we would like to hire you to custom build ours! ☺) We wonder if the natural fieldstone we’d like to use can withstand the high heat. Our only other concern would be that if we traveled in the winter we would not be there to keep the fire going and pipes would freeze. Thank you for any insights!

Our unit has a TempCast precast core, where the bake oven is also the secondary combustion chamber. Not sure about David’s setup, but many folks have them built into the side of the unit so they are not “in the line of fire”, so to speak.

Kathy,

First of all, it’s my home and I did help a bit to build the heater, but most of the credit should go to Alex Chernov of Stovemaster for the design, and my friend who is a mason for the construction. There might be a local mason with experience, but mine didn’t have any experience building a heater like this. We are in NW PA, near the Great Lakes, and we are probably the only masonry heater for many many miles around. Still, the instructions that came with Alex’s plans were clear enough that we figured it out. Be prepared for the cost, it’s a lot. I bought all the materials first and stockpiled them until I had what I needed, which helped spread it out a bit.

About the bake oven… ours is a black oven, which means that the fire passes directly through the oven. Alex gave us the option to choose a white oven instead, so that is an option if you really want that. Our heater looks similar to the picture at the top of this post. I don’t find the soot to be a problem for several reasons — a wood fired oven is largely about exposing the food to the wood aroma. Understand that you really aren’t doing a lot of cooking when the fire is newly ignited. Even pizza, which benefits from an oven that is about 600-700 F, doesn’t benefit from being cooked during the first 20 minutes of a fire when the oven temp is over 1000 F. The kinds of foods that you can cook during that initial phase are pretty much limited to steaks and burgers, and even those you should probably wait about 20 mins after the fire is started. I’ve come to understand that during the initial phase of the fire, when the wood is beginning to burn, there are a lot of aromatic chemicals being released as the wood actually ignites, that you don’t really want on the food. It can be overpowering in flavor, so I just wait until the wood is actively burning (black, not brown or tan) and then cook over that fire. You can keep cooking and using it like any other oven for many hours or even a full day later. Unless you’ve worked in a wood fired restaurant kitchen, you’ve never worked with heat like a masonry heater. It’s an extraordinary amount of power – it’s not just that it’s a hot oven, it’s also a convection oven because the air is moving and swirling around. For foods like pizza, I brush off the bottom of the bake oven floor with a straw broom before I place the pizza; I cook directly on the firebrick surface. Baking bread requires a much gentler heat, so I usually do that several hours after the fire has gone out. I broom off the floor, then just before I place the loaves I also swipe a sopping wet paper towel across the bricks to even out the temp and clean them off a tiny bit. The temperatures are so extreme that you are basically steam cleaning it. I always place a generous bowl of water inside the heater when I’m doing breads, for the moisture. You will eventually get the hang of it. Most foods don’t go directly on the floor though; I place a small rack similar to what goes inside of a toaster oven, which raises pans, slices of bread, and most other items a fraction of an inch off the floor. This helps reduce a bunch of problems, from burning the bottom of things to twisting and ruining baking sheets. Because of the rack, soot isn’t a serious issue. If there is too much soot on the floor I just sweep it back into the firebox with the broom.

You asked about materials… A masonry heater has a solid core of firebrick or a pre-cast core. No other material would be suitable for the core because of the high heat. However, outside of the core you can use any material, fieldstone, brick, tile, adobe, almost anything. The temperatures outside the core are much, much lower. There is a tiny gap between the core and the outer layer that acts as an insulating blanket that slows down the heat and smooths it out. Your fieldstone would work great as the outer layer.

And going away in the winter… it’s so funny, before building the house I had the same concern. I went to a lot of trouble to design a system that could withstand freezing, only to discover that there is a time-honored approach to this problem that is so obvious — before you go away you simply drain the pipes. This takes all of a few minutes. Be prepared, however, to do a lot less winter travelling, because winters are now a delight. Not only do we have the lovely, nearly free heat of the masonry heater, but winter is now my favorite time of year to cook; it’s pizza season!

David,

You have our heartfelt thanks for your wonderful, detailed reply! We expect to spend a lot on a masonry heater (and the associated materials) as it will be like yours I think, the centerpiece of the home. We truly appreciate all your advice!!

Kathy and Gary

David,

When you make pizzas are they small ones that fit on the ledges or do you somehow span it across the opening in the center of the oven? If you span it across, how do you keep the center from getting done too fast (burned)? Haven’t tried it yet. Thanks for the advice.

You don’t bake directly on the surfaces. You use a stone, like a pizza stone. This can be cleaned and the pizza can go directly on it. You can also bake items in a cast iron pan.

August,

A pizza stone would not work. If I put a “cold” stone in the oven it will break. All the instructions I have seen for pizza stones say that the stone must be in the oven at startup to prevent thermal stress cracking. My oven (Tempcast) is about 18″x18″ with a slot in the center of the floor 3″x14″ for the flame and smoke to pass through. This forms two ledges, one on either side of the slot, about 7-1/2″x18″ to cook on without interfering with smoke path. A pizza stone would cover most of the slot and choke the fire down. David said he cooks pizza directly on the firebrick floor of his oven. I could do this but the pizzas would have to be around 6-7″ in dia. Perhaps his oven has the smoke path to the side or along the back which would give him more continuous oven floor space.

Pizza stone works just fine, if you use it correctly. We’ve done it several times. We keep it in front of the stove while the stove is actively burning, so it preheats a little there. Once the fire is done burning, then we move the pizza stone into the oven area. What you don’t want to do it put a completely cold stone into a raging hot oven. That would indeed be likely to cause cracking.

Laurie,

I don’t have a ledge in front of my oven or bench under main doors to rest a stone on(I’m guessing that’s what you are doing). Been reading about pizza steels and cast iron. Apparently they work better for pizza baking and you don’t have to worry about the thermal stress cracking. Downside is they are heavier… I still have to figure out how to not obstruct the smoke channel if I’m going to cook with fire going. The Tempcast manual says to cook after the fire goes out but that’s not going to get the high temps for pizza. I’ve tried measuring oven temp after a fire and it’s in the mid 300’s. Either I’ll have to use a small pan/plate so as not to block much of the channel or elevate the pan off the oven floor with small metal blocks or something. Leaning toward elevating it as then the heat can travel under and around the entire pan.

If I recall correctly, the Tempcast manual also made the suggestion of a mini fire in the oven chamber to bump up the temp if needed. That may be an option for you.

Laurie,

You are correct. The manual does mention a mini fire in the oven. However, I don’t really see the point in doing that. If you have a mini fire going you certainly won’t have room to cook while it’s going and the ash would end up in your food. If you wait till the fire is out you are roughly back where you started. You just had the main fire blasting this area with super hot flames for the last 45 minutes or so. I don’t see a little fire adding much to that. I would think you would be better off trying to cook with the main fire if you want high temps. The Tempcast oven just isn’t designed to be used with a fire going (unless whatever your cooking fits to the side). It sounds like David has a much better layout in his oven with the slot along the back to cook with a fire. I’ll experiment and see if the elevated plate works. If I keep enough clearance around the plate it should work well.

I’m not implying that the fire be burned while the food is cooking, only that one could be burned to bump up the temp in the bake oven. Then you let the fire go out, brush away the ashes, and go on about your business.

I guess I just don’t understand the properties of the temp-cast model. I would think after burning a wood fire for an hour or two that the oven would be piping hot for many hours. In my case, at least, I could still bake a roast (temp. above 300 F) in the oven at least 8 hours after the fire has gone out, if I’m burning two fires a day. In the summer, or at the beginning of the heating season, cooking in the heater is frustrating and not really worth doing. It takes about three days to fully soak, and about three days to fully cool in the spring. I’m going to look up the temp cast and try to learn more about it.

You’re not missing anything. The TempCast oven does stay plenty warm for baking for hours after the burn, but if someone wanted to spike the temp a little higher with a direct burn in the bake oven itself, it’s possible.

Indeed I cook directly on the bake oven floor. The firebox is situated directly below the oven, and the combustion gasses come up into the bake oven by way of a slot at the rear. The gases then pitch forward due to the sloped ceiling in the bake oven, roll over, and exit to the sides into a double bell design. I had a pizza stone which lasted for a while, but it was no match for the heat and rather dramatically went through a “high speed disassembly”. In my oven at least there is no need for anything on the floor of the oven, except as noted in a previous post I actually keep a wire rack in there that lifts most foods off the oven floor by 1/2″ or so, which helps with not burning things. When pizza is on the menu, I take the rack out.

In terms of size, I make approx. 10″ pizzas, that is a maximum workable size inside the oven… it also happens to the best the size of most pizza peels and is the authentic size of a Neapolitan pizza pie.

As for the question of burning; it is indeed possible to burn a pizza if the conditions aren’t right. I’m not sure how to describe the correct temperature — very, very hot… but not in the first 10 or 20 minutes of a fire. Pizza restaurants will tell you that the idea temperature is somewhere around 750. There are several things I do to prevent burning, the most important of which is the dough itself. You want to have a high hydration dough, I make mine at 67% hydration and am experimenting with even higher water content. I dust the pizza peel with cornmeal, which act like little ball bearings that prevent the dough from adhering to the floor. Next, I do rotate the pizzas a bit as they cook, usually a 1/4 turn at a time through at least one full turn. And finally, they aren’t in the oven very long. They only take about 2 or 3 minutes. I use 1kg of flour to create 8 9-10″ pizzas and cook them all in rapid succession over about an hour.

Thank you David. Very helpful info to get started. A pizza is a terrible thing to waste…

Thank you for your insightful explanation of the pro and cons.

I’m not even in the market for a heater like this, but still found the article to be a worthwhile and informative read. You are making the internet a better place. Thanks!

You’re welcome.

I have built a large masonry heater in our home from scratch, and we also have an integrated oven. I really recommend it, it’s the heart of our home, and it is a dream to cook in. You cannot beat the power of an oven that is that hot. Fresh pizzas cooked from dough to done in 90 seconds! All of the ambiance of a wood fire without having to constantly stoke it and add wood to it. All of the costs and the huge amount of time it took have been worth it. In our part of the world, just knowing that the heat cannot “go out” or be interrupted by a power loss or any other external event is the kind of piece of mind that you cannot get any other way.

Just looked at this site and the above question. Lakeside design masonry heaters does have a design wth doors on both sides. The cores are built in Ontario but they have a Us patent number.

Hi we are thinking about incorporating a masonry heater into a cabin build. We were hoping to have the heater on the main level in the center of the cabin between dining and living areas. But then we wonder if it’s possible to have 2 sets of doors on it in order to be see-through? Can the fieldstone surround go all the way to the top of the cathedral ceiling that we want? Thank you and we appreciate your opinions so much! Sincerely,

Kathy and Gary

If you have a unit custom built, you should be able get it configured any way you want, it’ll just be expensive. The masonry stove kits that I’ve seen (Tempcast and Tulikivi) are all one sided, not see through. The difficulty lies in having space for the winding exit flue.

If you had a pass through unit (open to two sides), you could potentially wind to one side or the other before going up the chimney, but it would need to be a custom build, and there aren’t many who do that type of work. There’s no issue with expanding the masonry as far as you like, other than cost.

The tempcast units can have two doors. I have one with two doors and a bake oven. Love the fires!

Here is a link to my fiances’ website that has a picture of the unit along with pictures of the dome house we are building: http://www.lisadukowitz.com/dome-construction.html

@ Mike Leffelman,

It sounds like you’re taking your project very seriously. I have designed and built masonry heaters, good ones and not so good ones, for about 10 years. I’ve fixed the work of others as well. I’ve used computer modeling programs to design around theoretical gas flow through the system, and I’ve used the back of napkins. My own stove was built with no plans at all.

Trying to figure output of a stove can be frustrating. No one lives in a lab. In reality, the thing to do is to talk to someone who knows what they are doing about your home plans. Masonry heaters are very forgiving devices. While it is possible, as this blog indicates, to screw one up, most people are very happy with even a mediocre masonry heater.

I realize nobody lives in a lab and that every heater is different. What bothered me was that people will read this blog and see 79.5% efficiency study done by a university and think that is what to expect from them. Most people won’t go read the study for themselves and even if they did may not realize how poorly it was done. If your going to test something you have to isolate it as best you can. That wasn’t done at all in the Oregon study. These things are big and expensive. They are very efficient when built properly and have been built and tested in laboratories. I just didn’t want people to get and them pass on bad information. Defending the reputation of masonry heaters….

Absolutely. We do list the lab info because it gives a base-point to compare systems. The efficiency and “waste” are a big deal from a heating perspective. The more heat we can get out of wood the less wood we need to cut, haul, split, store and burn. Comparing the efficiency is more about saving our collective backs. As an example if you can get someone to build a good rocket stove with a long flue and an external feed, it will be better than than most masonry stoves and burn slightly higher ratios and burn more completely and simply.

Wow, your picture of your dome are impressive! What is on the outside of your dome? Looks like cement or stucco? How have you liked your masonry fireplace? About to build, trying to decide on if we want one or not.

Thank you Beth for your kind words. The outside of the dome is 3/4″ concrete over 7″ of styrofoam. The domes are kits from American Ingenuity domes in Florida. Mine has been a very long build (15 yrs and counting) as I did much of the work myself. Been living in the house for 13 months now and am very happy with the Tempcast heater. I’m estimating I will use about two cords of wood for heating this season. The house is located in SE Wisconsin. We recently discovered that the heater gets hot enough to bisque fire clay pottery! Decide not to try glazing as it will contaminate the bake oven. You do need larger fires to get the oven up to baking temperature. Have made cookies and cornbread so far. When the outside temperature stays below freezing I burn two 25-35lb fires a day. This will get the oven to 350-400 degrees after the fire goes out. The heater is capable of two 50lb fires per day but I haven’t needed that many BTU’s. It was expensive to build compared to a fireplace or stove but it’s efficiency, aesthetics and fire show are well worth it to me.

This is really interesting! Thanks for sharing!

Thank you for this informative article. I am not at the point of building, and my foundation sucks, so nothing in the near future, but for long term information, this will be useful for me! thank you for the “if we did it over” ! this is the most useful for someone who already did it; what they learned and how to improve for the next time! And also thank you for the actual http instead of simple links: my computer won’t load the links for the most part, so I have to put in the actual links from the original article in order to access the information.

Good information!

A good foundation is critical, even for the smaller stoves. I don’t think most people realize how heavy these beasts can be.

Do you have some sort of link blocker in your browser? We use malwarebites, which has been pretty reliable.

Very interesting; I have an epa stove. And the idea of creating a surround I find a good add on that I could do …

Thank you for sharing

Roland ♀