Common Blue Violet – Identification, Use, Folklore

This post may contain affiliate links. Read my full disclosure here.

The Common Blue Violet (Viola sororia) is a perennial wildflower found across much of eastern and central North America. With its heart-shaped leaves and rich purple-blue blooms, it has captured the admiration of gardeners and herbalists alike. Beyond its beauty, Viola sororia plays a valuable role in ecosystems, traditional medicine, and even culinary traditions.

Table of contents

Common Blue Violet Identification

The most recognizable feature of Viola sororia is its striking, five-petaled flowers. They are typically a deep violet-blue, though white, pink, and speckled forms also exist. (Viola sororia f. rubra is the pink form.)

Blue violets bloom abundantly in springtime with flowers that that resemble miniature orchids. There are five dark blue/purple petals and white throats. Blue violet flowers emerge on flower stems separate from the leaves, and are about 1″ (2.5 cm) across. The blossoms have a delicate and distinctive fragrance.

Common violets are perennial, blooming in the spring/summer and dying back in fall/winter. They propagate mostly by underground runners, but also produce seeds – but not from the purple flowers.

Seeds set in autumn on small green flowers without petals that hide in the foliage (cleistogamous flowers). You won’t damage your patch at all by harvesting the purple flowers. The cleistogamous flowers are self fertile, and produce seeds during the summer, which get ejected from the seed capsules.

The heart shaped leaves curl slightly at the edges, but flatten as they age. The leaves are high on individual stalks rising from the base of the plant. They spread readily once established in a moist, shady area.

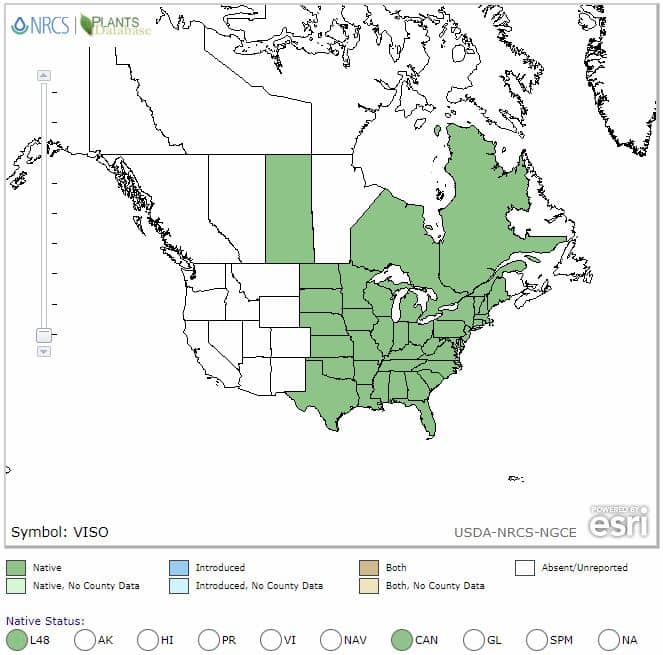

Where to find Common Blue Violets

Viola sororia is native to eastern North America. You will find it throughout most of the eastern United States and Canada. (source)

The range overlaps in some areas with viola odorata, which is native to Europe and Asia.

Look for these shade loving plants in moist woods and gardens, or a partly shaded lawn. (Many of the photos are from a friend’s yard.) They prefer rich silty loam or clay soil that is high in organic matter.

Uses of Common Blue Violet

Common blue violets have a long history of practical use. From nourishing foods to traditional remedies, Viola sororia offers a variety of benefits.

Food Uses

Please make sure to properly identify any plants before consuming. It’s best to harvest while the plants are blooming to make identification easier.

Both leaves and flowers of common blue violet are safe for human consumption. They are mild in flavor. Large amounts of leaves or flowers may have a laxative effect, so enjoy in moderation.

Look for younger leaves that recently emerged for best flavor. When used in soups, the leaves are slightly mucilaginous, giving them the nickname of “wild okra” in some areas. The flowers are often candied or added fresh to desserts for a splash of color.

Healing Wise by Susun Weed gives a plethora of violet recipes from vinegar and syrup to soup and salad. Susun sings the praises of sweet violets. She notes that 100 grams of fresh spring leaves contain:

- 264mg of ascorbic acid (a component of vitamin C)

- 20,000 IU of vitamin A

- An assortment of trace minerals

Make a simple violet vinegar for use in salad dressing. Fill a small jar with blossoms (don’t wash them). Cover with a good quality vinegar such as white wine vinegar, cider vinegar, or rice vinegar.

Put the lid on and let steep from 1-6 weeks before using. (The flavor becomes more pronounced as it ages.)

If you want more recipes, Healing Wise is the book for you. It’s a a whimsical exploration of seven common healing herbs and their uses. Samuel Thayer also has simple violet recipes in his book “Incredible Wild Edibles“.

Remember, the darker the color of the flowers, the darker the infusion. If you’re blessed with deep purple blossoms, you may want to try this beautiful violet jelly.

Medicinal Use

Traditionally, violets have been used for their soothing properties. They are considered cooling and moistening herbs. Medicinally, Susun Weed recommends violets for treatment of:

Would you like to save this?

- cancers

- relief from various breast ailments

- headaches (the plants contain salicylic acid)

- respiratory trouble

- wound healing

(Yes, all this this from a little blue flowered weed.)

Edible & Medicinal Wild Plants of the Midwest sites historical use of violets for respiratory issues, headaches, fevers, inflammation, and more. Recent studies using viola species extracts for cancer treatment showed reduced metastasis and cancer cell death.

The Backyard Herbal Apothecary features several violet preparations. Devon Young shares recipes for teas and infusions, syrups and creams. Healing Wise and The Backyard Herbal Apothecary are excellent compliments to each other.

Wildlife Uses

The flowers are not popular with pollinators, but are sometimes visited by mason bees and pollinating flies. Fritillary butterfly caterpillars eat the leaves.

Mice and some birds, such as mourning doves, eat the seeds. Deer, rabbits, and livestock will eat the leaves, but it’s not a preferred forage.

Folklore

In Greek mythology, Zeus created a field of violets for a lover he turned into a white heifer to avoid the wrath of Hera. In Roman mythology, Venus beat maidens blue and turned them into violets. Why? Her son, Cupid, said the maidens were more lovely than his mother.

Early Christians said that violets turned downward after the crucifixion, and viewed them as symbols of modesty and humility. Pagan cultures associated them with love and lust.

Most people have heard the simple children’s rhyme,

Roses are red

Violets are blue

Sugar is sweet

And so are you

The name has also come back in fashion in recent years. (Everything old is new again.)

Other Names

Common Blue Violet is also known as Pansy, Heart’s Ease, Jump-Up, Wild Pansy, Hens and Roosters, kiss-me-at-the-gate. Other names include purple violet, woolly blue violet, hooded violet, confederate violet, wood violet, and garden violet.

There are over 70 species of the family violaceae in the United States. Most have similar medicinal and food qualities. Some common species with purple flowers include Viola odorata (sweet), Viola papilionacea (wood) and Viola cucullata (marsh).

Note: These are a different species from African Violets (Saintpaulia ionantha). African violets have round, fuzzy leaves and are commonly grown as a house plant. Don’t eat Saintpaulia ionantha!

State Flowers

Violets are the state flower for Illinois, Rhode Island, New Jersey, and Wisconsin:

- Illinois (Purple violet – Viola)

- New Jersey (Viola sororia)

- Rhode Island (Viola)

- Wisconsin (Wood violet – Viola papilionacea)

More Ways to Use Wild Plants

This post is part of the Weekly Weeder series, which is all about wild plants. We share tips for identification, use, and sometimes, control.

Other posts in the series include:

- Recommended Wildcrafting Reference Books

- Creeping Charlie – Use and Control of the Shade Loving Ground Cover

- Benefits of Dandelion

Are you a fan of violets? Share your favorite ways to enjoy these beauties in the comments.

This article is written by Laurie Neverman. Laurie was raised on a small dairy farm in northwest Wisconsin, where she gathered wildflowers from the woods and pastures. She and her family now live in northeast Wisconsin, where they combine intentional plantings and semi-wild areas. Every season is a new opportunity to learn more about working with wild plants.

Originally published in 2012, updated in 2025.

have a bundle of these at my mail box and grabbed the flowers yesterday. thank you for sharing the info!

Do you know where I can buy some violet plants?

If you do a search on “buy common blue violet”, you should get a list of nurseries that stock the plants and seeds. You may be able to find a local plant swap group in your area with someone willing to share, given that they spread readily in the right conditions. I would hunt around for that option first. Or let friends know that you are looking for plants.

It is so funny that you shared this post this week! I made violet jelly for the first time last week! They were all OVER my yard, shade and full sun. I just couldn’t pass up the opportunity to try my hand at some foraging! My jelly turned out more lilac in color, but I think if I had picked more flowers, it might have been a deeper purple. (boy, it was labor intensive…gonna recruit the neighbor kids to help pick next time LOL!) The Jelly is simply amazing!

The flower jellies are a labor of love, but I enjoy being able to share something that friends and family will never find in stores.

We have no violets at our place yet (that I know of), but I should double check to see if the ones I transplanted from the neighbors last year caught. Their yard is filled with them, but we have little shade at this point. I planted them in the orchard, but the trees are fairly small yet.

Can you leave the flowers in instead of straining them out?

In the jelly? No, I wouldn’t recommend it. They won’t look pretty, they’ll just be mushy little blobs of plant.

The flowers from the infusion won’t be pretty, but maybe if you reserved some attractive blooms and pressed them up against the insides of the filled jars just before sealing?

Have you tried this? Curious if it would work or not, and how well the color would hold and if they would stay in position during processing. I think it would be safest with a full sugar jelly.

I made violet jelly with a mix of purple and white violets growing in the forest on our property, and the colour came out as such a lovely pinkish purple! Unfortunately I dont really smell the violet in the jelly, but there is a faint floral taste to it. The jelly is delicious and sweet.

Yes, the cooking fades the scent, but it’s still a lovely jelly.

Can I use vanilla extract instead of the lemon????

I noticed that when I made my clover jelly it also called for lemon.

My husband is not really fond of lemon.

So is there a reason we should use lemon or is it just for flavoring

The lemon juice isn’t for flavor, it’s to acidify (lower the pH of) the jelly to make it safe for canning. The finished jelly does not have a strong lemon flavor.

Ok, thank you. I guess I will go ahead and give it a try, even though I was so looking forward to that beautiful purple color! I think I am going to make some cupcakes today and whip up some of the flowers in the white frosting. I think that should really say spring, don’t you?

I was so looking forward to making the beautiful violet jelly, but my flower infusion turned out green! I didn’t use stems or leaves. Was I supposed to pick off all the flower petals? I would love to make this before the rest of the flowers go bad! Help!!

Some violets will naturally be lighter in color than others. The jelly in the photo was made from a deep purple patch of violets. When I make lilac jelly (with light purple flowers) the infusion is green and the jelly turns out golden in color. It still tastes good.

So are you supposed to pick the petals off so that the only thing you have is the purple ?

No, just nip the whole flowers off the top.

You can use the white violets too, right?

I’m not familiar with white violets, but I would think so.

oh good, lol! I was starting to panic that my violet infusion is green 🙂

No worries! I wish the lighter violets held color better, but the taste is still the same.

The reason violet jelly will turn green sometimes is that violets are pH indicators, just like purple cabbage and elderberries. The more acidic the mixture is, the more pink it will become. That’s why adding more lemon juice makes it hot pink. At the other end of the spectrum, more alkaline (base) mixtures will be closer to blue or even green. If you have enough of the dark purple petals it will still be fairly purple, but if you don’t have enough flowers in the mixture to really steep a dark color in or you don’t have dark purple flowers, then you’ll get green. Add a bit more lemon juice and it should turn pink.

It’s really fun to take advantage of this to teach chemistry to kids and make it seem a little magical. 🙂 I wrote a book on foraging elderberries and I do a lot of elderberry cooking with kids. I often make elderberry lemonade and they love to see it go from dark purple to hot pink when you add the lemon juice. We also make natural watercolor paint with elderberries and can have a huge spectrum of colors from green and blue to purple, red and pink, just from adding simple things like dish soap (alkaline) and vinegar (acidic).

I was wondering if those little voilets were good to eat…now I know…cant wait to

give them a try

Thankyou for your knowledge. 🙂

Wow, I’m so happy everyone liked my Homemade Body Wash post from last week! 🙂

Thanks to all who checked it out!!