Queen Anne’s Lace – Butterfly Host Plant and Blueberry Protector

This post may contain affiliate links. Read my full disclosure here.

Queen Anne’s lace (Daucus carota) is a biennial and is also known as Wild Carrot, Bird’s Nest Weed, Bee’s Nest, Devils Plague, garden carrot, Bird’s Nest Root, Lace Flower, Rantipole, Herbe a dinde and Yarkuki. In some states it is designated as a noxious weed.

Today’s featured weed is Queen Anne’s Lace, Daucus Carota

The World Carrot Museum states that the name “‘Herbe a dinde’ derives from its use as a feed for young turkeys – dinde.” (Personally, I’d never heard of that name before. Maybe it’s a UK thing?)

The Woodrow Wilson Foundation Leadership Programs for Teachers cites the origin of the name as follows: “Queen Anne’s Lace is said to have been named after Queen Anne of England, an expert lace maker. When she pricked her finger with a needle, a single drop of blood fell into the lace, thus the dark purple floret in the center of the flower.”

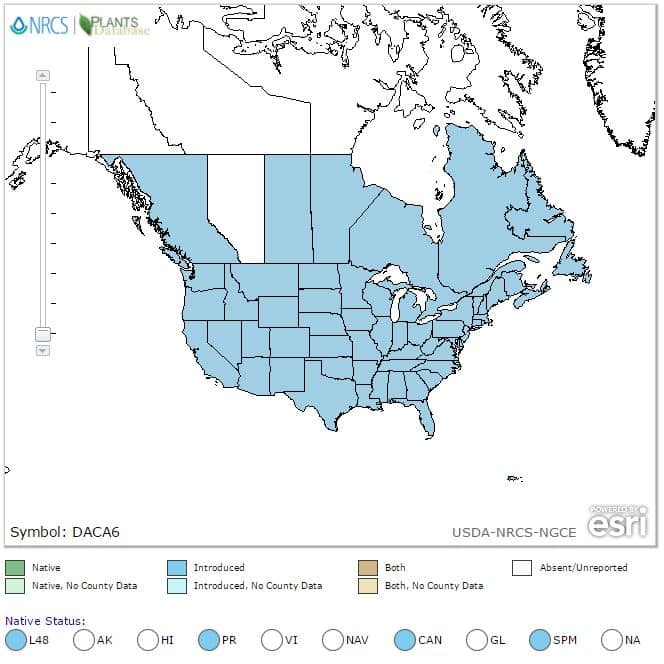

Range and Identification of Queen Anne’s Lace

Where does Queen Anne’s Lace Grow?

Queen Anne’s lace is commonly found along roadsides and meadows, and in gardens. Depending on your location it blooms May through August. If you spot what looks very much like a carrot, popping up where you didn’t plant any carrots, it’s likely a wild carrot. It is a native of temperate regions of southwest Asia and most of Europe and now thrives around the world.

Wild carrot is a biennial, like garden carrots. The first year it grows in a low cluster of leaves, the second year it shoots up a hairy flower stalk and then dies. Depending on conditions, some plants may flower the first year. (This also happens with garden carrots under stressful conditions such as extremes of moisture or temperature.) See “Growing Carrots – Quick Guide, Step by Step Instructions and Carrot Q&A” for more information on carrot cultivation.

Plants are 1-3′ tall, and have a white tap root. They will readily cross-pollinate with garden carrots.

Wild Carrot Leaves

The young seedlings look very much like carrots. The photo below shows wild carrot on the left, garden carrot on the right.

Queen Anne’s lace leaves are fernlike, up to 8″ long. The leaf type is twice compound, the leaf attachment is alternate (from the Wildflowers of Wisconsin Field Guide).

Note: The sap of Queen Anne’s lace can cause phytophotodermatitis, just like all members of the carrot family. Symptoms of phytophotodermatisis include an itching rash and blisters. For more info on phytophotodermatitis and how to avoid it, see “My Worst Gardening Mistake – Parsnip Burn AKA Phytophotodermatitis“.

Queen Anne’s Lace Flowers

Wild carrot flowers are borne on a hairy stalk shooting out from the base leaves. Flower heads are 3-5″ wide, and are composed of dozens of tiny white flowers, each 1/” across. In the center of the flower head, there is a single purple to black floret. (Not every flower head has this dark floret, but it is common.)

Although I think the flowers are quite lovely, I’m careful to avoid letting them go to seed in the garden. A single plant can have hundreds of seeds, and they stay viable in the soil for years. (Why is it that wild cousins are so much more durable than their domesticated counterparts?)

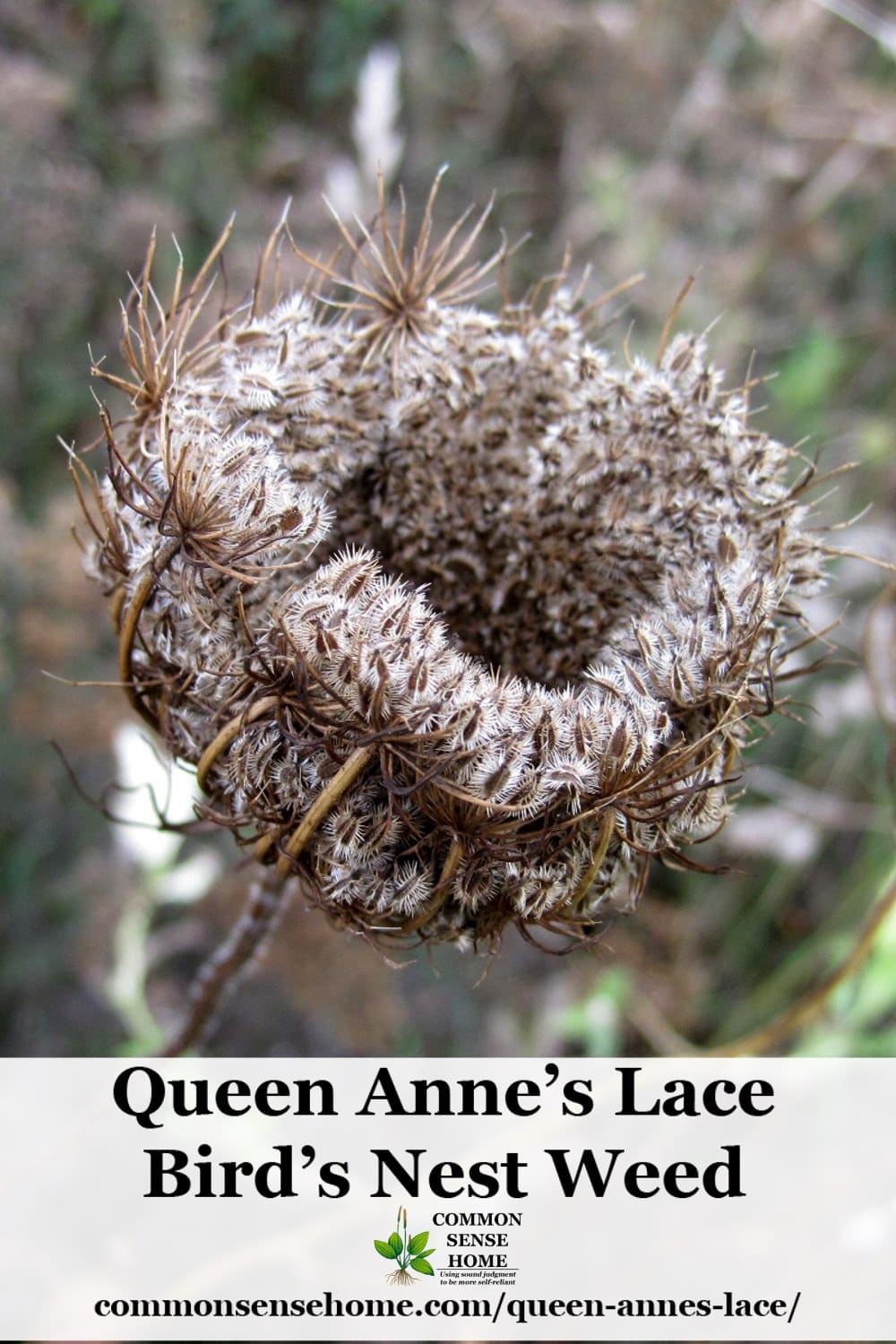

When the seed heads dry, they curl up into a “nest” shape, accounting for the various “nest” names. Guy Queen Anne’s lace seeds here.

For related information on weeds, I really enjoyed Susun Weed book Healing Wise.

Wildlife Uses of Queen Anne’s Lace

The plant acts as a host plant for the black swallowtail butterfly.

If you’re interested in raising butterflies in your home or learning more about butterflies, I highly recommend The Family Butterfly Book. I prefer the swallowtails on wild carrot instead of my garden dill or carrots.

Illinois wildflowers details wildlife uses of wild carrot:

The nectar and pollen of the flowers attract primarily small bees, wasps, flies, and beetles. Wild Carrot Wasps (Gasteruption spp.) are among these floral visitors. Other insects feed destructively on the foliage, roots, and other parts of Wild Carrot (Daucus carota). These species include root-feeding larvae of Listronotus oregonensis (Parsley Weevil), root-feeding larvae of Ligyrus gibbosus (Carrot Beetle), root-feeding larvae of Psila rosae (Carrot Rust Fly), foliage-eating larvae of the moth Melanchra picta (Zebra Caterpillar), and foliage-eating larvae of the butterfly Papilio polyxenes asterius (Black Swallowtail); see O’Brien (1997), Arnett & Jacques (1981), Cranshaw (2004), Wagner (2005), and Bouseman & Sternburg (2001). Another insect, Melanoplus bivittatus (Two-striped Grasshopper), feeds on the foliage, while Allonemobius allardi (Allard’s Ground Cricket) feeds on the umbels of flowers (Gangwere, 1961).

Wild Carrot is a summer host for such aphids as Cavariella aegopodii (Willow-Carrot Aphid), Dysaphis apiifolia (Hawthorn-Parsley Aphid), Hyadaphis foeniculi (Honeysuckle-Fennel Aphid), and Hyadaphis passerinii (Blackman & Eastop, 2013; Cranshaw, 2004). Among vertebrate animals, seeds of Wild Carrot are eaten by the Ring-necked Pheasant, Ruffed Grouse, and Pine Mouse (Martin et al., 1951/1961). The aromatic and somewhat bitter foliage of this plant is browsed sparingly by mammalian herbivores. Occasionally White-tailed Deer will chomp off the upper half of flowering plants during the summer, while the Cottontail Rabbit occasionally eats the lower leaves (personal observation). The burry fruits containing the seeds can cling to the fur of some mammals and the clothing of humans, thereby introducing them to new locations (Lacey, 1981). The foliage of Wild Carrot is preferred as nesting material by the European Starling. Because of the antibacterial and insecticidal properties of the foliage, this appears to benefit the health of hatchlings by reducing the number of nest lice and other parasites (Clark & Mason, 1985; Clark & Mason, 1988).

Food Uses of Queen Anne’s Lace

Queen Anne’s Lace contains vitamins K, B and C; pectin, lecithin, glutamine, phosphatide and cartotin; and it has flavonoids and essential oils.

Would you like to save this?

As the name “wild carrot” would imply, the root of Queen Anne’s lace is edible, as are the leaves and flowers. Queen Anne’s Lace roots are high in sugar. CAUTION: Pregnant women should not consume Queen Anne’s lace in any form, as it may cause uterine contractions.

Before using any part of the plant, make sure you do not confuse it with wild hemlock or water hemlock, which both look similar and are poisonous. The stem of poison hemlock is smooth with purple splotches, while the stem of queen anne’s lace is hairy with no splotches. Queen Anne’s lace smells like carrot when the foliage is crushed. Wild hemlock smells musty. For more details and photo comparisons, see “How to Tell the Difference Between Poison Hemlock and Queen Anne’s Lace“.

Harvest roots for cooking during the first year, before the plant goes to seed. Romans, early Europeans and early Americans cultivated and harvested Queen Anne’s lace. They boiled and ate the roots. The roots can also be dried, roasted, ground and used as a coffee substitute, in a manner similar to chicory. The young leaves can be eaten in a green salad or tossed bits into soups as a spice. The flower heads can dipped in batter and fried as fritters.

Queen Anne’s Lace jelly is delicious – delicate and floral with a hint of peach flavor. For an added twist, pair it up with red currants. You can check out the recipe in the post “Queen Anne’s Lace Jelly with Currants“.

Craft Uses of Queen Anne’s Lace

For those of a crafty inclination, wild carrot flowers can be pressed and dried and used as decorations. They keep their form very nicely. You may enjoy using them for homemade greeting cards, scrapbooking or decoupage. If you don’t have access to your own, dried pressed flowers are available for purchase, such as these on Amazon. Historically it was also used as perfume, by simply socking the flowers in in water.

The flower heads of the herb when simmered in a pot of water have been used as orange/yellow dye. If you treat your undyed textile/fiber with alum and cream of tartar and then dye it with the flower head mixture, it will give a longer lasting dye.

You can also use the flowers for a nifty science experiment to show how plants draw up water using capillary action. Simple clip some blossoms (try not to smash the stems) and place them in some water with food coloring in it. The blooms will slowly change color as the plant draws in water from below. You can keep it simple, or make up a multi-colored arrangement.

Medicinal Uses of Queen Anne’s Lace

Ryan Drum has more experience with Queen Anne’s Lace than most, and shares it on his site, Island Herbs.

The Woodrow Wilson Foundation Leadership Programs for Teachers offers the following outline of medicinal uses:

Traditionally, tea made from the root of Queen Anne’s Lace has been used as diuretic to prevent and eliminate kidney stones, and to rid individuals of worms. Its seeds have been used for centuries as a contraceptive; they were prescribed by physicians as an abortifacient, a sort of “morning after” pill. The seeds have also been used as a remedy for hangovers, and the leaves and seeds are both used to settle the gastrointestinal system.

It is still used by some women today as a contraceptive; a teaspoon of seeds are thoroughly chewed, swallowed and washed down with water or juice starting just before ovulation, during ovulation, and for one week thereafter. Grated wild carrot can be used for healing external wounds and internal ulcers. The thick sap is used as a remedy for cough and congestion.

Research in China has confirmed that the seeds are an abortifacient. The leaves of Queen Anne’s Lace and carrots contain significant amounts of porphyrins. Porphyrins stimulate the pituitary gland and may lead to increased levels of sex hormones.

Other historical uses for Queen Anne’s Lace included treatment of bladder conditions and reportedly reduced or prevented gas/flatulence.

(bactericidal) Early American settlers and traditional Chinese used Queen Anne’s lace sometimes mixed with honey to create a poultice for sores or ulcers, providing anti-bacterial protection.

Queen Anne’s Lace Attracts Beneficial Insects in Organic Blueberry Patch

I received an interesting comment when discussing weeds on LinkedIn from an organic blueberry grower who uses the plants to attract beneficial insects.

Theodore E. James Jr. shared this information:

As I wrote to you, we have planted Queen Anne’s Lace amongst our certified organic (Certified by Oregon Tilth) blueberries. They attract a parasitic wasp that attacks the drosophila fly that is spreading throughout the Pacific Northwest, attacking blueberries, cherries, blackberries, and other soft skin fruit. We do not have spray the drosophila because of the wasps solving the problem for us!

Here’s a photo of his Queen Anne’s lace in action.

Learn to Use and Appreciate the Weeds

“Weeds” are just plants that grow without being planted – or where you may not want them – but they serve a purpose. I always tell the boys, “Nature abhors a vacuum.” If there is an empty niche, it gets filled. Our weeds hold the soil in place, plow compacted subsoil, draw up nutrients, provide medicine, feed wildlife (and people) – they are a treasure, not a curse. As you tend your yard and garden and the soil improves, unwanted volunteers will either disappear on their own, or be much easier to manage.

Recommended resources:

- Wildflowers of Wisconsin

- Nature’s Garden: A Guide to Identifying, Harvesting, and Preparing Edible Wild Plants

- The Forager’s Harvest: A Guide to Identifying, Harvesting, and Preparing Edible Wild Plants

- Backyard Foraging: 65 Familiar Plants You Didn’t Know You Could Eat

- Edible Wild Plants: Wild Foods From Dirt To Plate

Thanks so much for stopping by to visit. Help stop the overuse of herbicides by spreading the word about putting our weeds to work and sharing this post.

You may also find useful:

- Top 10 Edible Flowers, Plus Over 60 More Flowers You Can Eat

- The Weekly Weeder Series

- My Favorite Wildcrafting Resources

Originally published in 2011, updated in 2017.