Chicory – Prebiotic, Coffee Substitute, Health Tonic

This post may contain affiliate links. Read my full disclosure here.

Welcome to the Weekly Weeder series. Today’s featured plant is chicory, Chicorium intybus. The wild and domesticated varieties of chicory have a long history of use for food and medicine, and as a forage crop for livestock.

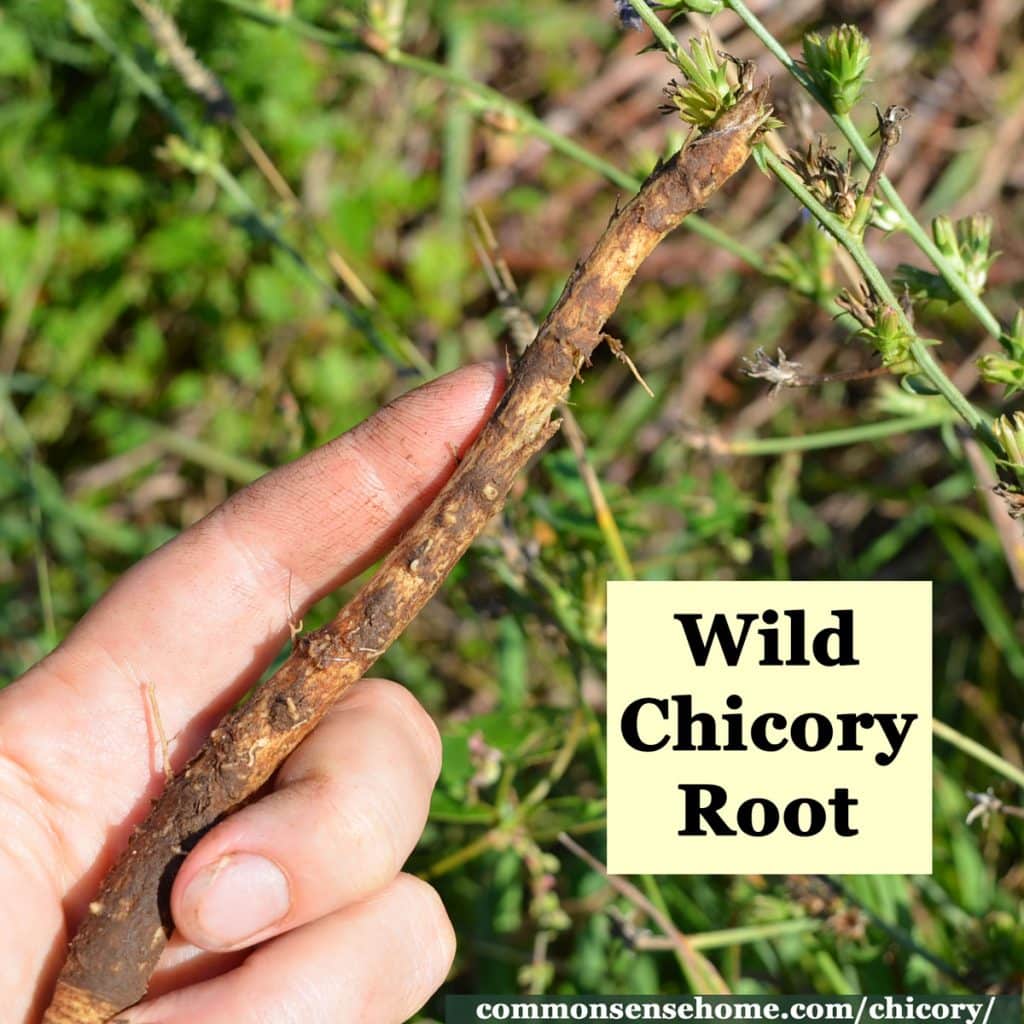

Chicory is prized for its long taproot, which is roasted and used as a coffee substitute or coffee additive. The roots are also high in inulin, which is used as a sweetener and prebiotic. The plant contains compounds such as flavonoids and coumarins that may help fight disease.

What is chicory?

Chicory is a perennial plant that has a basal rosette with long, toothed leaves similar to a dandelion (thus the name “blue dandelion”). It grows 1-4′ tall, with ground level leaves that are 3-6″ long. The leaves that alternate up the flower stalk are much shorter, 1/2 – 1″ long, and wrap around the stem.

The plants have a long taproot that can punch through some of the toughest soils. The domesticated varieties have a thicker, more substantial root, something like a sugar beet. (The domesticated plants are cultivated and harvested much like sugar beets.)

The roots of some varieties of domesticated chicory (Witloof chicory) are forced to produce a vegetable known as Belgian or French Endive.

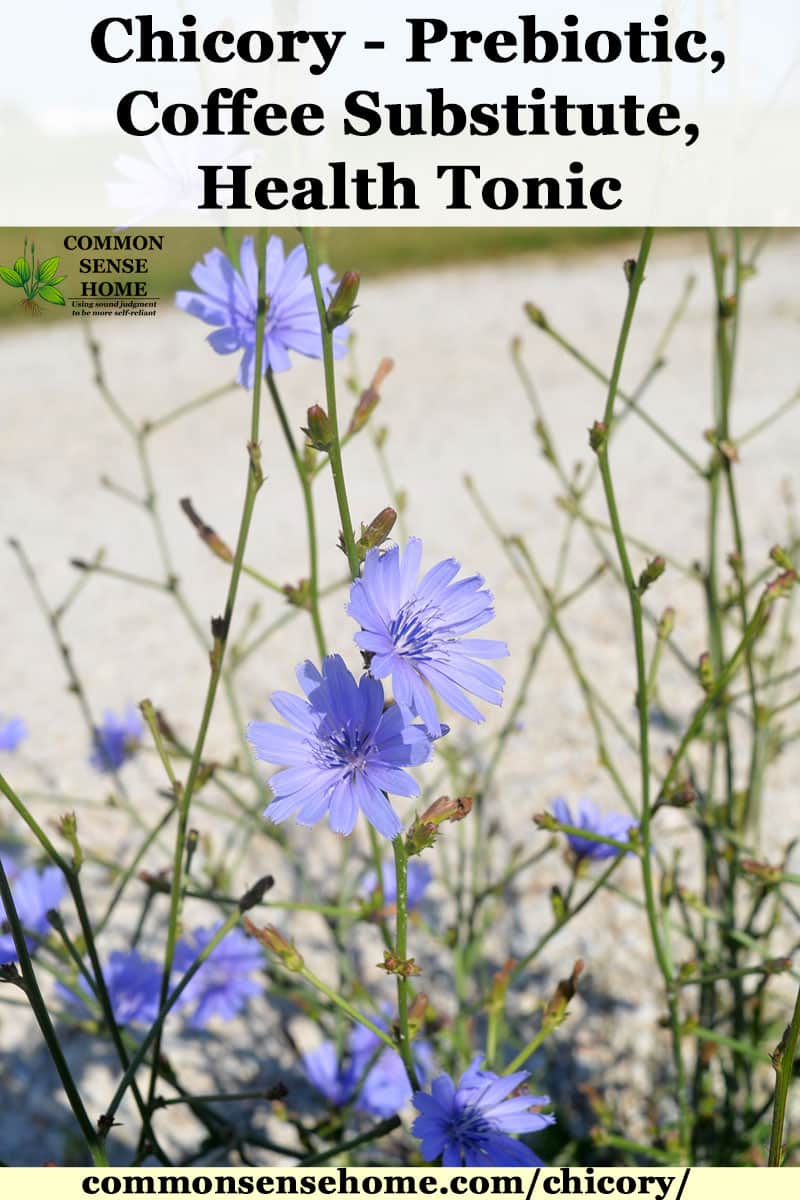

Chicory Flowers

Bloom time is summer and fall, from July through October. Chicory flowers are roughly 1.5 ” across with up to 20 petals. They open in the morning and close by early afternoon. Each petal is tipped with a tiny bit of fringe, like a scarf. Flower color ranges from white to pink, but in our area I have only seen blue..

When chicory flowers, it shoots up a long stem with multiple blossoms that open one at a time and last only one day. Although not as striking as some flower displays, thick clumps of chicory still make a lovely splash of blue in the countryside. The flowers don’t smell like much. When my great niece and I went out to smell them, she said, “It smells like barnyard”. Yes, perhaps a bit, but the odor is faint.

You probably don’t want to let the flowers go to seed in large numbers in areas where you frequent. They produce hooked seeds that latch onto clothing, somewhat like burdock burrs. These seeds are oblong, flat and about 1/4 inch long. I once let a large patch of them go to seed on our rock wall at our old place (the flowers were so beautiful!), and that was a mess.

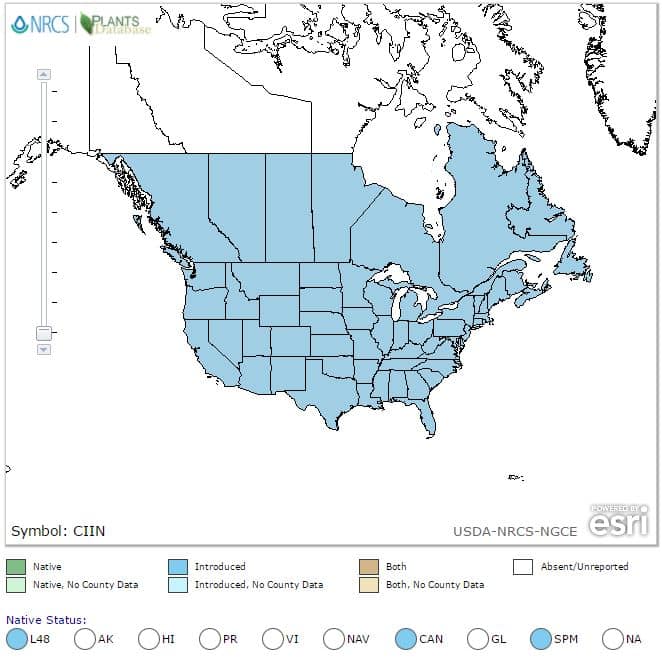

Where Does Chicory Grow?

Chicory is believed to have originated in Europe, but is now common in North America, China and Australia. Around here, chicory grows in large clumps and is common along country roads, combining with birdsfoot trefoil to paint the countryside with bold swaths of blue and yellow. Its long taproot punches down through clay, gravel and compacted soils, thriving in rough conditions. The USDA range map shows that is common throughout the United States.

Chicory Health Benefits

The article “Studies on Industrial Importance and Medicinal Value of Chicory Plant” lists a wide array of studies noting the use of chicory for digestive issues, heart disease, as an anti-thrombotic and anticorcinogenic, to reduce arthritis pain, to reduce constipation, as an immune system booster and promoter of kidney health. Most of the featured studies focus on chicory root extract, but drinking chicory root tea or coffee or consuming chicory may also have some positive impact on these conditions. The list below highlights some of the medicinal uses of chicory.

Note: As mentioned above, most chicory studies focus on chicory root extracts or compounds that could be measured and replicated in lab experiments. Chicory may be helpful for the listed conditions, but you should always consult a trained healthcare provider, especially in the case of serious illness.

Acts as a Prebiotic

The inulin in chicory acts as a prebiotic, supporting the growth of healthy bacteria in the gut. Specifically, chicory promotes the growth bifidobacteria. These probiotic bacteria are found in cultured foods such as yogurt and cheese.

May Improve Bowel Movements and Delay or Prevent Diabetes

Chicory root extract may help you poop better and delay or prevent the onset of diabetes.

May Inhibit Cancer

A 1999 study examined the growth of cancer tissue in mice and found that those mice placed on a diet consisting of 15% oligofructose, inulin or pectin reduced tumor growth. The control group was fed only starch as their carbohydrate.

May Relieve Arthritis Pain

Chicory root extract was tested on patients with osteoarthritis in the hip or knee, and found to provide some level of relief from pain and stiffness.

May Promote Weight Loss by Increasing Satiety

In another study, the introduction of oligofructose (OFS) such as chicory derived inulin led to lower levels of ghrelin, the so called “hunger hormone” that stimulates appetite and better weight management.

Chicory has Antibacterial Properties

Chicory extracts were tested against gram positive and gram negative bacteria, including Staphylococcus aureus and Salmonella typhi. The chicory extracts were found to be more effective at inhibit bacteria growth than other materials tested.

Sources:

- Prebiotic effects of chicory inulin in the simulator of the human intestinal microbial ecosystem

- Effects of the extract from roasted chicory (Cichorium intybus L.) root containing inulin-type fructans on blood glucose, lipid metabolism, and fecal properties

- Influence of Inulin and Oligofructose on Breast Cancer and Tumor Growth

- Phase 1, placebo-controlled, dose escalation trial of chicory root extract in patients with osteoarthritis of the hip or knee

- Oligofructose Promotes Satiety in Rats Fed a High‐Fat Diet: Involvement of Glucagon‐Like Peptide‐1

- Phytochemical and Antibacterial Studies of Chicory: (Cichorium intybus L.) – A Multipurpose Medicinal Plant

Medicinal Uses of Chicory

Gardens Ablaze gives the following suggestions for medicinal use of chicory:

Chicory teas taken internally are believed to be effective in treating jaundice and liver problems. Additionally, as with many other herbs, a tea made from roots or leaves appears to be useful for those with digestive problems.

Save a little tea and try dipping a cotton ball into it for a refreshing and soothing eye wash. You can also add a spoonful or two of honey to thicken and use as syrup for a mild laxative for kids. For long-term use, try drying and pulverizing Chicory leaves into a powder for use in capsule form. Please see How to Make Herbal Capsules for more information.

For external use, bruise fresh Chicory leaves and apply to areas affected by gout, skin eruptions, swellings, skin inflammations, and rheumatism.

Would you like to save this?

Chicory Side Effects

Consuming small amounts of chicory in food is likely safe for most adults. Large amounts may cause gastrointestinal distress. The inulin ferments in your digestive tract, producing excess gas and associated issues. (Eat an “energy bar” loaded up with chicory and you’ll see what I mean.)

If you are allergic to members of the daisy family, such as ragweed, be cautious with chicory, as it may also cause an allergic reaction.

Don’t use medicinal quantities of chicory while pregnant, as it may induce a miscarriage.

For those with diabetes, large amounts of chicory may lower blood sugar. Avoid medicinal amounts of chicory before and after surgery. It may interfere with blood sugar control.

If you have gallstones, chicory may cause problems, as it stimulates the production of bile. (Source)

How to Make Chicory Coffee

Chicory roots are dried, roasted and ground, and then brewed like coffee. A good family friend who recently passed away, Mike Jacisin, used to be a regular chicory “coffee” consumer. Mike was one of my early wildcrafting inspirations.

To make chicory coffee:

- Dig roots in early spring or late fall, when they are not flowering.

- Scrub the roots well and trim off tops.

- Chop and dehydrate the roots using a commercial dehydrator or air drying. If you chop the roots into smaller pieces before dehydrating, they will dry faster. (Think small rounds or bits, roughly even in size so they will roast evenly in the oven.) Air dry on a rack for a week or two at room temp, or dehydrate at 95°F (35°C)in a commercial dehydrator for 12-14 hours.

- Roast the dried roots for 20 to 60 minutes at 325°F (163°C), until they are brown and brittle. Think “coffee roast color”.

- Grind in a coffee grinder, spice mill or blender.

- To brew chicory coffee, you may use it as you would regular coffee in a dip coffee maker or French press. Alternatively, boil 1-2 teaspoons of ground, roasted root in one cup of water for about three minutes. Pour into coffee strainer or French press and let drip or strain.

- Store roasted roots, ground or unground, in an airtight container.

For more herbal coffee ideas, check out the post 8 Herbal Coffee Alternatives.

Eating Chicory

Chicory leaves are edible and rich in nutrients, like dandelion leaves, but extremely bitter. If you can find them, the small rosettes of early spring are the most palatable. Those who don’t mind bitter greens can use the young greens raw (sparingly) in a salad. Cook older leaves with a couple of changes of water. They’ll still be bitter, but less bitter. The white bases (or crowns, as Samuel Thayer calls them) of older plants can be trimmed of the bitter green leaves and eaten. The white base is somewhat less bitter than the green leaves.

In The Flower Cookbook, Adrienne Crowhurst makes pickled chicory flowers. I have not tried this, but the recipe sounds interesting.

PrintPickled Chicory Flowers

A unique wildcrafted condiment for the adventurous eater.

Ingredients

- 2 cups chicory flowers or flower buds

- 3 cups white wine vinegar

- 1/2 teaspoon salt

- 1/4 teaspoon ground ginger

- 1 cup brown sugar

Instructions

Wash the chicory buds or flowes in ice cold water; drain. Place them in a sterilized canning jar (or jars). In a saucepan, bring the vinegar, salt and ginger to a boil. Simmer for five minutes. Remove mixture from heat and add the sugar; stir until dissolved. Pout this liquid over the flowers and buds in the jar(s). Seal and store in a cool place for at least one week before using.

Chicory Forage

The Ohio State University Extension document “Use of Forage Chicory in a Small Ruminant Parasite Control Program” notes that chicory contains secondary plant metabolites called sesquiterpene lactones, which may help to reduce the parasite load of small ruminants. Some varieties are more effective than others, and may prove to be a viable alternative to chemical dewormers.

The study “Chemical Composition and Nutritive Benefits of Chicory (Cichorium intybus) as an Ideal Complementary and/or Alternative Livestock Feed Supplement” cites the benefits of chicory inulin for livestock digestive health, reduced parasite loads with ingestion of chicory, and increased reproductive rates of sheep on chicory forage, among other benefits.

Wildlife and Forage Uses

Illinois Wildflowers shares the faunal associations of Chicorium intybus:

The flowers attract short-tongued bees and probably other insects. Both nectar and pollen are available as floral rewards. The foliage of Common Chicory is eaten by Melanoplus bivittatus (Two-Striped Grasshopper), Melanoplus femurrubrum (Red-Legged Grasshopper), and probably other grasshoppers. The larvae of a lizard beetle, Acropteroxys gracilis, bore through the stems of this plant, while the caterpillars of the moth, Pyrrhia exprimens (Purple-Lined Sallow), feed on the the flowers, buds, and developing achenes.

While chicory does provide a nectar source for bees, it produces a yellow, bitter honey.

Other Names for Chicory

Chicory is also known as Achicoria, Barbe de Capucin, Blue Daisy, Blue Dandelion, Blue Sailors, Blue Weed, Bunk, Cheveux de Paysans, Chicorée, Chicorée Sauvage, Cichorii Herba, Cichorium intybus, Cichorii Radix, Coffeeweed, Common Chicory, Cornflower, Écoubette, Herbe à Café, Hendibeh, Hinduba, Horseweed, Kasani, Kasni, Racine de Chicorée Commune, Ragged Sailors, Succory, Wild Bachelor’s buttons, Wild Chicory, Wild Endive, Wild Succory,Witloof and Yeux de Chat.

Sources: Ohio Perennial and Biennial Weed Guide and WebMD.

Learn to Use and Appreciate the Weeds

“Weeds” are just plants that grow without planting – or where you may not want them. They serve a purpose. I always tell the boys, “Nature abhors a vacuum.” If there is an empty niche, nature fill it. Our weeds hold the soil in place, plow compacted subsoil, draw up nutrients, provide medicine, feed wildlife (and people) – they are a treasure, not a curse. As you tend your yard and garden and the soil improves, unwanted volunteers will either disappear on their own, or be much easier to manage.

Recommended resources:

- Wildflowers of Wisconsin

- Nature’s Garden: A Guide to Identifying, Harvesting, and Preparing Edible Wild Plants

- The Forager’s Harvest: A Guide to Identifying, Harvesting, and Preparing Edible Wild Plants

- Backyard Foraging: 65 Familiar Plants You Didn’t Know You Could Eat

- Edible Wild Plants: Wild Foods From Dirt To Plate

Thanks so much for stopping by to visit. Help stop the overuse of herbicides by spreading the word about putting our weeds to work and sharing this post.

You may also find useful:

- Top 10 Edible Flowers, Plus Over 60 More Flowers You Can Eat

- The Weekly Weeder Series

- My Favorite Wildcrafting Resources

Originally published in 2011, updated in 2017, 2018.

Laurie, thanks for all the information you provide. I have been a subscriber to Common Sense Home for multiple years and never delete before reading, unlike many other articles in my inbox :).

Many articles have been saved or pinned for later accessibility. I was interested in the herbal coffee idea, I had not heard much about it, although I was familiar with chicory. Thanks again for your information and insight into living well.

Pat (Virginia)

You’re welcome, Pat, and thanks for not deleting my emails!

I started drinking chicory ‘coffee’ when I had to give up regular coffee for the heavy acid. Don’t know if chicory is as acidic, but it doesn’t bother me. I love the nutty taste!!

I was very interested in reading your article on Chicory as I have it growing in my pasture, however, there were so many ads and popup video ads that I could not get more than a few words read before more ads popped up. I tried everything to get them to stop playing and close them but they would start back immediately.

Very discouraging!

You may want to check your browser, as you may have a browser add on that increases ads on websites. It’s a type of malware.

Our ads can be closed and don’t start back up immediately.

no one mentions if you can freeze ground roasted chicory- anyone know?

Sure. For best storage life, I’d vacuum seal, or at the very least, store in an airtight container.

Thank you so much for all the interesting informations, looking forward to continue reading the other pages about weeds! 🙂 Garden calendar has a new entry to forage my backyard for chicory and dandelion roots come fall! I’m intrigued by the pickled Chicory flower recipe… what would they be used for once they are ready?

I use them in salads or as a garnish for meats. Pickled anything helps improve digestion.

im doing it right now i let them dry for 3 day tho when i squish the root they do crip noise instend of wet noise. i will try 60 min for the roast i hard its could be more. So i will try to figure by the color.

Interesting those of you commenting on the “bitterness” of chicory! Ever TASTED coffee? B.I.T.T.E.R.!!!

I was a non-coffee drinker until a few years ago, but still had to have some coconut sugar and heavy cream in it to ward off the bitterness! Until I was diagnosed with T2Diabetes. So….stopped drinking it. Got a substitute with both chicory and dandelion roots, which is….bitter! Stopped drinking THAT, too. Then I read about ‘bitters’ something people take ON PURPOSE for better digestion, and health. Now, I do have real coffee and /or add the coffee substitute powder to it, for the health benefits…no sweetener, and it tastes just fine to me. Bitter? Well…yes, but I tolerate it for the health benefits and since I only drink one cup in the morning once in awhile, I think it is fine. But, coffee itself is bitter, as are the plant root based substitutes people use….maybe that is why they use them, BECAUSE they are bitter, just like coffee!!!

lol – one of the reasons I’m not more of a coffee fan is the bitterness. I tend to prefer the milder blends over dark roasts. To me, it’s not the bitterness, per se, it’s the difference in overall flavor. It’s an acquired taste, but I find it pleasant enough now that I am used to it.

Every year when I see Chicory plants in bloom, I think of all the books I’ve read about the ‘frontier days’ when pioneers were always drinking chicory ‘coffee’. I wondered at their process for making it. They must have patiently dried it in the sun (on their wagons?) while traveling, and roasted it in pans over the fires. Can you imagine the patience that it took? Not being addicted to coffee, I’d pass. My husband would desperately drink anything resembling coffee, lol. I should try this, this summer. Thanks.

After years of working with herbs, I’ve developed a whole new level of appreciation for what historical herbal users must have done.

I drink roasted chicory from the store and I love it (I’m not a coffee drinker) so I’m curious to make my own and see how it compares! I don’t tolerate caffeine very well so I really enjoy drinking it when I feel like having something other than my herbal tea. Thank you so much for sharing!

You’re very welcome.

My husband and I have pretty much sworn off of coffee but miss the roasty flavor. I adapted a recipe I saw on the Mountain Rose website by adding a few chai type spices and a healthfully indulgent dollop of whipping cream:

Bring 1 pint of water to a boil. Stir 2 to 3 heaping tsp. of roasted chicory root. Bring to a gentle boil for 2 minutes, turn it down to a low simmer. This is when we stir in about 1/4 tsp powdered ginger, and 1/8 tsp ground cardamom. Pursue the low simmer for 2 min. Remove from heat, cool a bit. Strain and pour into mugs. This is pretty concentrated, so we typically dilute our brew with some hot water and save the rest of the concentrate for iced chicory tea later. We add our hot water, honey or maple syrup and a dash of cinnamon, then a generous dollop of cream. It tastes like warm gingerbread smells. You may intensify the gingerbread-iness by using molasses as the sweetener, but we indulged last winter in many cups of chai chicory. We didn’t find that we got the kind of buzz you get from coffee, but did read that overuse of chicory may exacerbate inflammation, an issue for my husband, so he quit drinking it. The article we read also commented that an excess of chicory can irritate the gut. Chicory is known for its inulin content and is processed for use as a pre-biotic. One is supposed to slowly increase use of inulin to avoid the irritation. I didn’t have problems with it initially, but after a few months noticed my daily cup was followed by a slight cramping of my small intestines and more bowel activity than I felt was necessary. I nave cut back to an occasional cup on a chilly day and am back to experiencing it as a delightful treat. It occurs to me that I cold look for mugi-cha. a roasted barley tea that farmers in Japan enjoy. I’m not sure it wold go well with cream, but it makes a satisfying beverage, no sweetener needed.

The lovely delicate blue of the chicory flower also caught my eye when walking to work, long before I tried the beverage. I was considering growing it as a fodder for my chickens, and appreciate the fine detail that it is more suitable for other kinds of livestock before I grow my own lovely but persistent mess!

I’ve tried chicory coffee. As a former Starbucks barista I’ve got to say it’s pretty good! Tastes very much like coffee.

I recently learned about cold brewing coffee. Basically you put about a cup of ground coffee in a quart jar and fill with cold water. Let it steep overnight then strain. You’re left with a very strong coffee concentrate. When you want a cup just fill you mug about 3/4 or so full of hot water add a few tablespoonfuls of your concentrate and sweetener and cream as you like it. My husband really likes it this way…never bitter.

I wonder if this might be a way to overcome the bitter factor of chickory coffee?

I’ll have to keep an eye out for chickory and give it a try.

Michelle – that’s a really interesting idea. Thanks for sharing.

I love these weekly weeders! I noticed these plants in front of our home today next to the road and simultaneously thought a) the piece by the road is getting overgrown and b) I wonder what the name of those pretty weeds are and if I can do anything with them. 🙂 I’ll be saving this post. Not a big coffee drinker either (ok, not a coffee drinker at all) but I might try the roots just for the fun of it!

Do you think it would be ok to use the roots even though it’s by a medium traffic road?

I generally avoid harvesting from roadsides, but it’s really up to you.

Maybe we need to have a "taste off"? Chicory, Queen Anne's lace, and dandelion. 🙂

Great post, Laurie…we'll have to try this in the fall. I am a two-three cup per day coffee person, so I'd be interested in channeling my inner Laura Ingalls with this!

Annette – I haven't tried it yet, but I'm not a very big coffee drinker, either. Dandelion is so bitter – so far my favorite way to consume it is wine! I will try it at some point, just to say I have. 🙂 It sounds like chicory "coffee" will be quite bitter as well (the leaves sure are).

I tried dandelion coffee a few years back and it was terrible. Maybe I'll let some of my Italian chicory go to seed and try again. I never knew it was non-native. Interesting! Did you try it?

Glad that you are finding the site interesting.

I am new to your site and still have to catch up on all of your blogs. Since I started reading the other week what you are doing is fantastic. My favorite is last one.

Thanks for sharing Laurie! When I lived in Milwaukee, there was an empty field behind our home and it was covered in chicory! It was sooo beautiful that I had to bring some in and put them in a vase for the table. I never noticed a smell, and although I had heard that the roods were used as a coffee substitute, I never tried it.

Thanks for bringing back the memory!

~ Kathy @ Mind Body and Sole

Dmarie – I have to say it has it's moments. 🙂 I'm planning to try homemade mayo soon, too. I bought a stick blender, but it's been so very busy I haven't had a chance to tackle it yet.

hey, I think I saw that flower on a recent walk! Love it that you try to learn something new each day. I just accepted a challenge to learn something new for 30 days, so yesterday I made homemade mayo for the first time. It's going to be a fun 30 days…but you must have a fun LIFE! look forward to seeing more of your blog–thx!