Passive Solar Heating Basics

This post may contain affiliate links. Read my full disclosure here.

As some of you know, in our home we use three different heating sources – passive solar, a masonry stove, and radiant in-floor heating warmed by a combination of active solar water heating and a propane boiler. I can’t give firm numbers, because we have very minimal monitoring set up, but I’d estimate that the passive solar and masonry stove cover roughly half of our heating load. On sunny days (even in the dead of winter), it can carry the entire load, retaining heat well after the sun has gone down. Of course we have some stretches of weather with no sun at all, so we need backups.

In this post I’ll discuss passive solar heating basics, roughly adapted from the book, “The Solar House: Passive Heating and Cooling” by Daniel Chiras, much simplified, with examples from our own home.

Table of contents

- #1 – Choose a Site with Good Solar Exposure

- #2 – Orient the East-West Axis of a House Within 10 Degrees East or West of True South

- #3 – Locate Most Windows on the South Side of a House

- #4 – Minimize Windows on the North, West and East Sides

- #5 – Provide Overhangs and Shading to Regulate Solar Gain

- #6 – Provide Sufficient, Properly Situated Thermal Mass

- #7 – Insulate Walls, Ceilings, Floors, Foundations and Windows

- #8 – Protect Insulation from Moisture

- #9 – Seal Houses Against Air Infiltration But Provide Adequate Air Exchange

- #10 – Design Homes so that each Room is Heated Directly or is Accessible to Solar Heat

- #11 – Create Sun Free Spaces

- #12 – Provide Efficient, Properly Sized Environmentally Responsible Back-Up Heating

- #13 – Protect Homes from Winds by Landscaping or Earth Sheltering

- #14 – Synchronize Daily Living Patterns with Solar Patterns

- Is Passive Solar Heating Right for You?

- Related Articles

#1 – Choose a Site with Good Solar Exposure

No sun = no passive solar heat (or any other sort of solar). If you’re building new, look for a site that has good sun exposure from 9 a.m. to 3 p.m. during the heating season (10 – 2 will do in a pinch, but more is better). If you’re considering a retrofit of your existing home, look for south facing facades without shading, either on your current dwelling, or for a possible addition.

Consider the orientation of the house on the site. Ideally, you are looking for a longer, narrower building (usually rectangular, unless you’re using unconventional materials) – longer from east to west, shorter from north to south. This gives you a nice, long wall facing the sun, so that the sun can reach the majority of the interior space.

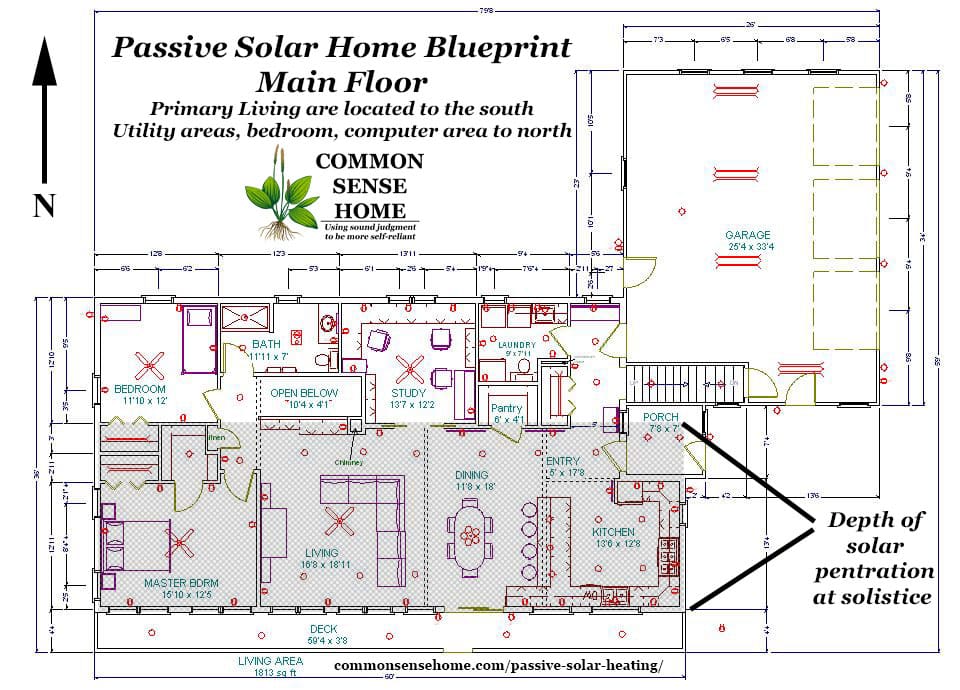

On the main floor of our home, we have the main living area – kitchen, dining, living room and master bedroom, along the southern exposure. The northern exposure houses a half bath/laundry, pantry, computer room, bathroom and boys’ bedroom. At winter solstice, sunlight penetrates through the entire south living area.

If you have trees, you can use a solar pathfinder (or hire a solar consultant with a pathfinder, since they are somewhat pricey) to give you a clearer picture of just how much the trees (or other obstructions) will interfere with solar gain.

#2 – Orient the East-West Axis of a House Within 10 Degrees East or West of True South

As mentioned above, more exposure = more solar gain. For effective solar heating, you really do need to have the bulk of your windows pointed at the sun. This means south facing in the northern hemisphere and north facing in the southern hemisphere. We have a compass rose marked on our acid stained basement floor, at the base of the steps, that accurately reflects the home’s orientation.

When building new, you may be able to work with a difficult lot by using an L-shaped home design to line up a portion of the home to the street while leaving the bulk of the home aligned for better solar exposure. Note how our garage opens to the east so that we avoid northwest winds blowing snow in front of the garage and morning sun exposure will help melt snow and ice buildup in front of the doors, while the house itself stills aligns east to west.

#3 – Locate Most Windows on the South Side of a House

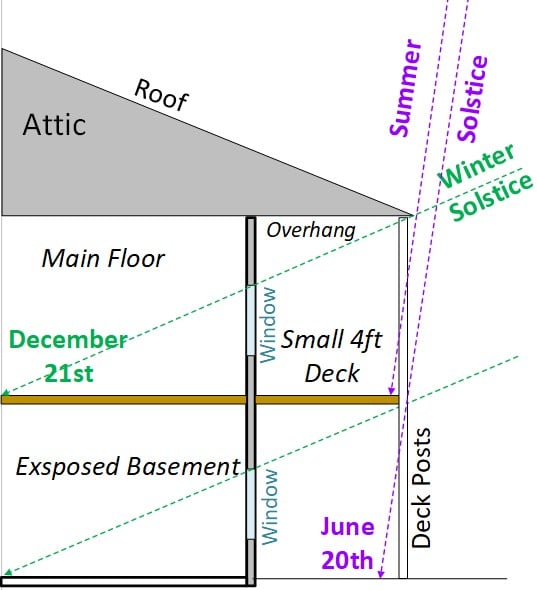

Putting your windows on the south side gives you the best return on investment for passive solar gain. Sure, at times you may have plenty of sun pouring in from the east or west, but that sun is hard to manage for solar gain. During the summer, the sun angle will be higher in the sky. During winter, the sun angle is lower. When you have south facing windows and properly sized window overhangs, summer sun will be blocked and winter sun will naturally shine right in. For those in the southern hemisphere, concentrate windows on the north side.

#4 – Minimize Windows on the North, West and East Sides

As I mentioned above, the gains from east and west are hard to control because they can’t be easily effectively shaded. North windows only lose heat, they won’t gain. We do still have some windows on these walls for daylighting and cross-ventilation.

#5 – Provide Overhangs and Shading to Regulate Solar Gain

You must have a way to shade those big south facing windows in summer, or you will roast. I think most people who have looked into solar building design at all have seen some of the lovely gems from the 1970’s with huge banks of angled south facing windows – and absolutely nothing to block the sun. Those early passive solar designs were more like sun ovens than comfortable living space. Even greenhouses use shade clothes in the summer to block excess heat at times.

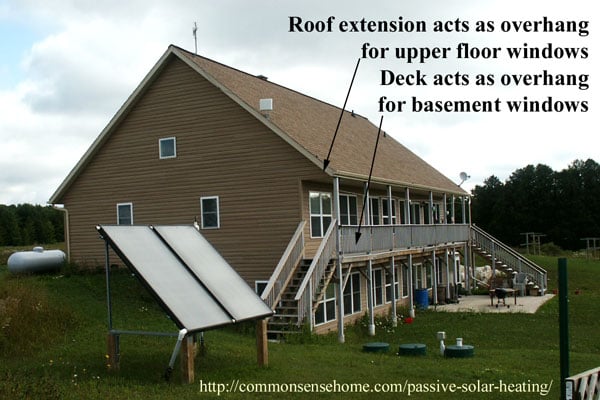

In our home we extended the roofline to provide shading for the main floor, and ran a small deck along the south face of the house to act as the overhang for the windows in the walk out basement.

Other shading options include, but are not limited to:

- Awnings

- Exterior Rail Blinds

- Sunscreens

- Trellises with Vines

- Deciduous Trees

- Other Deciduous Plantings

Shading works best when provided outside the home, so the excess heat never enters the building envelope. Sustainable by Design has an online overhang design tool to help you properly size and orientate your overhangs.

#6 – Provide Sufficient, Properly Situated Thermal Mass

Large, bulky things change temperature more slowly. It’s physics. Maybe you’ve noticed in the kitchen, working with stoneware, heavy cast iron or crockpots. Even after you turn off the heat, they don’t cool down very quickly. The same principle can be applied in our homes.

On our home, we’ve used ICF (insulated concrete form) construction for all of our exterior walls, from basement to roofline. ICF walls house a layer of concrete (laced with rebar) between two layers of insulation. They are thick, heavy and airtight – and have a lot of thermal mass. We also have ceramic tile throughout much of the home, a masonry stove, concrete floors in the basement with a sand bed below the floor to act as a heat sink. All of these elements combine to create a home that holds a steady temperature much more easily than a conventional stick built home. See “ICF Construction – What You Need to Know About an ICF Home” for more detailed information about ICF construction.

If you are building new, consider thicker exterior walls with materials such as:

- Concrete

- Brick

- Strawbale construction

- Cob

- Adobe

Interior elements are more easily retrofitted by the addition of tile, stone or concrete countertops, masonry heaters (these can be a little tricky, but are possible) and other bulky items.

#7 – Insulate Walls, Ceilings, Floors, Foundations and Windows

Whether you’re interested in passive solar or not, insulating your home well is the first step I recommend to anyone looking to reduce their heating and cooling loads. I remember when we were house hunting, and we’d go into the basement of some homes and could see daylight winking through the outer walls at the foundation line. Bad, very bad. Great Day Improvements, LLC has some very nice charts showing the R-values of different types of insulation, and recommended levels of insulation for different parts of the country.

The first winter we moved into our home, we noticed a very large amount of heat loss from our uncovered south facing windows. After doing some research, we decided on double honeycomb cellular shades, because they have a relatively high r-value and were easy to install. These shades create an insulating layer of air to keep the warm air in and cold air out.

Would you like to save this?

#8 – Protect Insulation from Moisture

The down side to sealing up your home to make it more energy efficient is that the moisture from daily activities can build up in inappropriate places, potentially leading to mold and rot problems. Vapor barriers and effective use of natural and forced ventilation such as stove vents, drier vents, ceiling fans, bathroom fans, HRVs (heat recovery ventilators) and ERVs (energy recovery ventilators) can help avoid moisture related problems in your home.

#9 – Seal Houses Against Air Infiltration But Provide Adequate Air Exchange

Remember, any insulation job won’t work very well if there are holes and gaps in the insulation. Pay special attention to any perforations in your building envelop, such as attic access points, outlets, ventilation pipes, and can lights. These can contribute to significant heat loss from a home.

If you have a forced air heating system, don’t forget to insulate and properly seal your ductwork so that the heat gets where you need it and not where you don’t – such as an unused basement or attic.

If there is a need to bring in additional outside air in winter to replace stale indoor air, consider and HRV or ERV. Both of these units feature an air-to-air heat exchanger that transfers some heat from the outgoing indoor air to preheat the incoming outdoor air. ERVs also reclaim some moisture. See “HRV or ERV? How to choose the right mechanical equipment for a balanced ventilation system in your home” for more information.

#10 – Design Homes so that each Room is Heated Directly or is Accessible to Solar Heat

Open floor plans are our friend for this concept, because everything is connected to everything else. Of course, this makes it a little trickier if you want to isolate infrequently used areas, but you can work with what you have. Also, sound really carries, especially with the tile floors. Down side = it can get noisy, upside = I always know if they boys or cats are getting into mischief.

Upstairs and downstairs, we have direct sun and indirect/no sun areas. The utility and food storage areas are a natural fit for the no sun basement areas.

#11 – Create Sun Free Spaces

Your first impulse might be to think that every part of a passive solar home should be bathed in sunlight. Not so. The biggest problem with that option in our modern world is that TV and computer screens don’t like glare. That’s why we stuck the home office on the north side. We do the little TV watching we do during the evenings, for the most part, so that’s rarely an issue. (We have one TV in the house, and it’s older than the kids.)

Sometimes full sun can get a bit roasty, too, especially if you have someone who doesn’t like light and heat. My friend, Julie, lives in a basement apartment, so it can be a little overwhelming for her when she visits mid-winter and gets baked in full sun. She swore one time she was getting a sun tan on the coach. Me, I like it. The cats and I sit and soak up the rays.

#12 – Provide Efficient, Properly Sized Environmentally Responsible Back-Up Heating

When we were building, we ran into all sorts of headaches with this one. By default, a stick built home that’s the same size as ours would normally require a much larger conventional heating system. Work with your contractor or a trained solar design professional to make sure that you are sizing any back up heat correctly. A system that’s too big will cost more money up front and work less efficiently once operational.

#13 – Protect Homes from Winds by Landscaping or Earth Sheltering

Having lived in an wind-whipped area for close to ten years now, I can absolutely confirm that strong winds will suck the heat right out of you and out of your house, if it’s not protected. One of our first planting projects was a windbreak to the north and west of the home. The evergreens are now finally getting to the size where they are starting to protect the house and yard, but it’ll be a few more years before we see the full sheltered micro-climate that we want. Trees, fences and outbuildings can all be used to help buffer the main residence.

Earth sheltering is another way to take advantage of thermal mass, this time on the outside of your home. We implemented earth sheltering by building a walk out ranch style home. Other options include earth berms built up alongside the north side of the home (and sometimes the west and east) and fully earth sheltered buildings where the dirt comes right up over the roof.

#14 – Synchronize Daily Living Patterns with Solar Patterns

One thing that is largely glossed over in much of what I read about passive solar that I want you to know is that a passive solar house means an active solar homeowner. To get the best performance from your passive solar home, you need to do certain things on a daily basis, like opening and closing blinds. You could automate this, but in general it’s not a huge time-eater.

As a blogger, I take advantage of natural daylighting patterns and time my cooking and projects so that I can get the best natural light on the subject. We also add an additional layer of insulation to our north and west windows for winter in the form of thin film window coverings. Our windows are only double pane, and adding that extra layer really helps cut down on condensation in the window wells in the deep of winter. Because we also have an active solar water heating system, I try to time laundry to wash mid-morning, so we have enough sun to heat the water and enough daylight hours to dry the laundry on the line.

Is Passive Solar Heating Right for You?

If you’re building, I’d certainly consider it as an option, because much of what makes a passive solar house work are the same concepts that make any well-designed home work. If you’d like to dig into more details, I highly recommend reading “The Solar House“, as I’ve only summarized our implementation of one chapter in this post. The whole book is over 250 pages, jam packed with charts, maps and lots of examples of the good and bad of solar architecture.

If you’re remodeling, you may also be able to add some passive solar features, or perhaps a sunroom or greenhouse for growing plants or additional living space.

Have you considered adding solar to your energy mix? I’d love to hear more about your experience. Just leave a comment below.

Related Articles

Hi Laurie!

Hubby & I have been trying to retrofit our existing 1959 brick ranch home with new insulation & cellular shades for a couple of years now.

Have you ever considered doing a blog post on retrofitting an existing home with passive solar design principles?

I can’t find much info on the subject but would love to learn more. Thanks!

Hi Cheryl.

The basic principles are the same whether you are dealing with building new or retrofitting.

Take advantage of the southern exposure.

Use appropriate overhangs so you don’t bake in the summer.

The insulation and cellular shades will serve you well year round.

You can add thermal mass elements (heavy furniture, tile flooring, planters, etc), but the glazing and overhang are the most important parts for passive solar.

We are considering a ICF home to build and I’m impressed with the amount of information that you provide on your multiple pages. Thank you for your information. It is making our decision much easier.

Thanks for your wonderful information on the heating basics of passive homes. I found the info very informative and concise. I am in the process of educating myself on passive homes. I am planning on building on in the next few years. Would you mind sharing the square footage of your home and the cost per square foot ? Thanks again.

The house is about 1850 sq ft on the main floor. Given that the house is nearly 13 years old, cost per square foot is out of date, and I don’t have a number for it anyway. Given the ICF construction and some other details, it was more expensive than the average home being built at the time, but costs less to heat and cool and is easier to maintain and to live in.

We also have a Passive Solar Heated Home and just love it. Our home use all of the techniques of yours except radiate heated floors and we use a masonnary wood stove that heats our poured concrete And steel beam walls. All of the homes techniques really help in heating during the -10 degree days in Indiana.

Thanks for reminding us of just how great our home is.

Do you find that the steel beams transmit heat through the walls? That was a concern of ours when we were considering different construction techniques. Their strength level is great, that’s for sure.

Do you have the floorplans for the rest of the house? Do you sell the plans if someone is interested in building it?

The plans on the site can be used (just share the site with friends contractors and such as “payment”). CommonSenseHome accepts no liability or responsibility if you end up hating the prints or they end up not working. (sorry for the legalese)

We might publish a Common Sense Home – Home Building book someday. In the meantime, Best of luck! Building is a very exciting process!

Great info!!!!

Wow! That’s a lot of great information, Laurie! Some day I hope to be able to build a home and have thought about many of the options for heating and cooling. We’re considerably further south than you are and don’t have to worry much about snow, but winds here can get brutal.

Thank you for being so thorough!

Thanks, Mark. The ICF does a great job blocking the winds.