Papaya Ringspot Virus in the Garden – Control and Prevention

This post may contain affiliate links. Read my full disclosure here.

This is a guest post by Debra Ahrens.

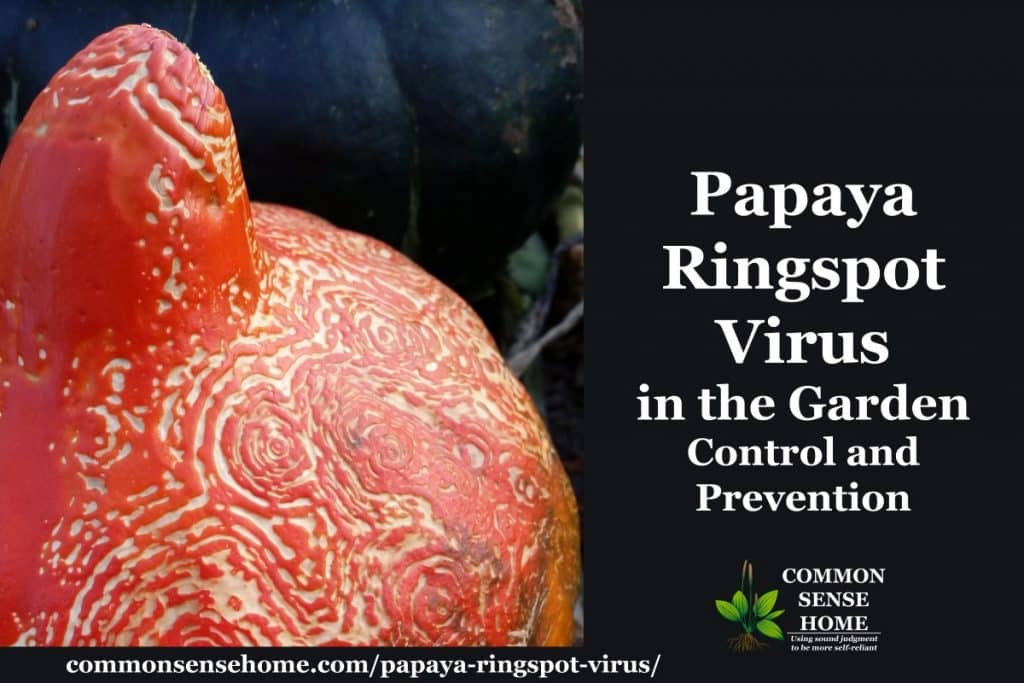

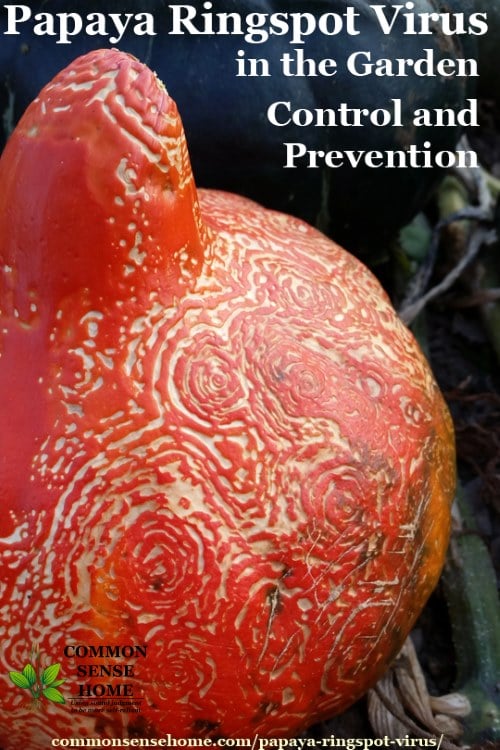

The spirit of Vincent Van Gogh visited my squash patch! Lest you think I have been sniffing the catnip, look at this squash! When we found this, we gazed at it in wonder. The intricate pattern is definitely not random. Did my artistic son sneak into the garden and prank me with this complex artwork? The vibrantly colored red Kuri squash looks as if someone took a teeny tiny woodburning tool and painstakingly etched a wonderful pattern just into the outer skin of the fruit, leaving the inner layer of the hull intact.

When we found a second one, we knew this was not a prank. We posted a photo and a wise Common Sense Home reader told us that this was caused by a disease, the papaya ringspot virus, also known as papaya mosaic virus.

Say WHAT?! What is that and what is it doing in my Northeast Wisconsin garden? (We certainly don’t have papayas nearby.) I had to do some research, which I’ll share here with you.

What is Papaya Ringspot Virus (also known as Papaya Mosiac Virus)?

PRSV (papaya ringspot virus) is a plant disease more commonly found in warmer climates on papayas. This disease decimated papaya production in the 90s. There are two types, PRSV-P and PRSV-W. It seems that the first affects papaya and cucurbits, while the latter only infects cucurbits– cucumber, melon, pumpkins, and squash. The virus, spread by aphids, causes symptoms in the plants within three weeks.

In papayas, young plants die quickly, while older, productive plants show yellow leaves which drop. The fruits have blemishes, and the compromised trees produce fewer and smaller fruits until they eventually die. Apparently, all infected trees die. The papaya growing industry was nearly wiped after the disease first appeared in Hawaii in 1992.

Unable to find any way to prevent the spread of infection, even by aggressively removing diseased trees (a practice that goes by the name of roguing), research turned to genetic modification. No resistance to the virus was found in the cultivated papaya trees, but resistance was found in wild cultivars of the Carica species. Unfortunately, these were sexually incompatible with the papaya producing plants.

By splicing genes from the wild species into the Carica papaya, an immune response to the PRSV was developed. The two transgenic papaya strains are called Rainbow and SunUp. These transgenic varieties now comprise a majority of cultivated papaya in Hawaii. Consumption of the fruits from the transgenic papayas have demonstrated no adverse effects in humans, but studies have been limited.

Papaya Ringspot Virus also Called Watermelon Mosaic Virus

But what is PRSV doing in my squash patch? Despite my search, I have no idea how it got there. Apparently, the papaya ringspot virus type W was formerly called watermelon mosaic virus type 1 here in our growing areas. There are also a couple of other mosaic viruses that produce damage on our cucurbits.

Can I eat the damaged squash? Yes. The squash looks too beautiful to eat, BUT it is safe to consume.

Can other plants get this? PRSV Type W affects all cucurbits. This would be squash, pumpkins, watermelons, cucumbers, and gourds. Type P will infect papayas as well.

Would you like to save this?

Should I collect all my cucurbit vines to destroy the virus? That is not necessary. The disease is spread by aphids in a non-persistent manner. It does not spread from plant to plant directly.

Can I still save the seeds? Yes, the virus lives in aphids, not in the plant material.

Papaya Ringspot Virus Prevention

What can gardeners do to prevent future problems? Control the aphids! There are a number of ways to control aphids, including;:

- Physically remove them with water pressure

- Dilute soap solutions which work by dissolving the waxy coating on the little aphid bodies

- Homemade bug control sprays or ready-made organic sprays

- Creative use of plant materials– This includes cultivating trap crops away from your patch to attract the aphids TO the alternate plants or planting and interplanting repellent plants such as onions and garlic in your patch and around your garden. In my patch, the aphids had many lovely lambs quarters to dine on so this may have contributed to the viral presence in my squash. Weed hosts of the mosaic viruses include the lovely:

- wild cucumber

- lamb’s quarters

- clovers

- pigweed

- mallows

- Creative use of animals– Attract beneficial and predatory insects to your land. Ladybug larvae LOVE aphids, but there are other insects such as lacewings that will eat aphids, as well.

The first solutions will also affect beneficial insects. I prefer to concentrate on growing healthy plants with enough diversity of plant material to provide a balanced environment for our insect friends.

Overall, I did not have any significant plant loss or fruit damage, so we’re not seriously concerned. Next year we’ll keep a closer watch on the weeds, and focus on plant health and a balanced ecosystem with predatory insects.

You may also enjoy other posts listed on the Gardening page, including:

- How to Start a Garden – 10 Steps to Gardening for Beginners

- Small Garden, Big Yield – 10 Tips for a Great Harvest

- The Ultimate Guide to Natural Pest Control in the Garden

References

- Gene Technology for Papaya Ringspot Virus Disease Management – The Scientific world Journal

- Papaya Ringspot Virus – Established on Maui – State of Hawaii Department of Agriculture

- Recombinant DNA Technology and Transgenic Animals

This post is by Debra Ahrens. Debra lives with her family on a five acre hobby farm in northeastern Wisconsin which she often describes as ‘short on hobby, long on farm’. Besides the School of Hard Knocks (Life), she attended UW-River Falls, majoring in Dairy Science. Along with her husband Jerry and their three youngest daughters, they raise every kind of domestic poultry known to man, and maybe a few that shouldn’t be known. Their furry animal family includes a flock of Suffolk sheep, dairy goats, a few rabbits, their dog and a lone beef heifer, Thelma. In her spare time, Debra is a poultry and sheep project leader for Kewaunee County 4-H.

Thanks, Debra, for the biig heads up!

I grew up in Hawai’i and was living and working there when papaya frrarms were failing due to the rampant spread of papaya ringspot.virus. Organic papaya farmers were prospering beyond their wildest dreams before that and feeling pretty good about being able to offer such a health giving, luscious fruit to their North American organic cousins. They told a slightly different story with a slightly different chronology including gmo strains that were ntroduced before ring spot began to appear. The University of Hawai’i conducted extensive research on this disease and gmo varieties, a notable portion of which of which was funded by the GMO industry. While working for a naturopath and small farmer On Maui, I encountered a very innovative farmer who discovered that Bokashi compost kept his non-GMO papaya trees in robust health and produced mammoth, flavorful sweetly succulent papayas without blemish of any kind. He had quit trying to market his papayas, this being well into the disaster, but he was very generous with friends and family. While living on the continent I found that I felt like I had gotten a good dose of of mold when I ate health food store Sunset and Sunrise red papayas. Consuming them in Hawai’i later gave me this reaction. I grew up on this fruit, which I both love and find I was healthier on when I could access the yellow-orange fleshed varieties that are still grown locally for farmer’s market consumption. While living in Madison I grew some squash that had a different pattern incised on the skin. I thought it was insect predation, and wonder if it is the other specie of virus instead. It looked spookily like Sanskrit or Arabic cursive writing. This was in 2003 to 2010. Since then I have bought property and begun to garden in NE Central WI, Lat 47. So far we have not seen either disease in our garden, but I wonder if the milder weather we have had for a few years and have been told is a longterm trend, will make it a friendlier environment for these diseases. Bokashi requires tropical temps that I only get consistently (in a warm year) in summer. We are pretty much off grid, so that includes indoor temps., too. I’d love to have a workaround strategy to protect my curcubits and hope this post yields some good info. Paul Stamets has done brilliant research into the immune-protective qualities of mycelia. I don’t know if he tackled ring-spot, but he thinks he has nailed bee colony disorder with arboreal forest King Stropharia. With that guy, results are only a matter of time and attention!

Ooops! I was thinking about my Madison days and remembered that the strange patterns appeared on the squash SEED hulls. So is this a symptom of the other virus?

Please write about how to make Bokashi compost

We’ll look into it this growing season. I have not worked with it to date.