Autumn Olive – Uses, Control, Recipes

This post may contain affiliate links. Read my full disclosure here.

Autumn Olive (Elaeagnus umbellata) is one of the most widely available wild fruits in the United States. Since it’s considered invasive in many areas, you’re doing a public service by eating the berries. Plus, it’s also quite tasty, and loaded with lycopene. We share foraging and identification tips, plus ways to use this abundant, adaptable crop.

I first discovered autumn olive when we moved to our current property over 18 years ago. We built our home in an abandoned pasture, and a neighbor mowed the pasture each year to keep down the brush.

As we settled in, I started taking a closer look at the various plants growing on the property. There were some pretty red berries, and I wondered if they were edible. After some researching, I realized that we had autumn olive plants.

Since then, we’ve stopped mowing the entire acreage, and instead are turning it into a food forest and semi-wild area. We’re using the autumn olives as nurse plants to protect other trees from the winds, and harvesting the berries. They also make good wildlife habitat.

History of Autumn Olives in the U.S.

Autumn olives are not native to North America, but found their way here in the early 1900s. Originally from East Asia, they were introduced as an erosion control and wildlife food source. Since then, they’ve made themselves at home in many parts of the United States. You can find the plants up into Canada and even on the Hawaiian islands.

It’s funny to me that the plant was planted and spread by the same government agencies that are now trying to eradicate it. These shrubs will thrive on mine tailings and other nasty soil where less hardy plants struggle to survive. They withstand drought and temperature extremes, while fixing nitrogen in the soil.

It’s considered an invasive species in many areas because it displaces native plant communities. The shrubs leaf out earlier than many native species, giving them a jumpstart on the growing season. Since they are nitrogen fixing, they change soil biology. This can be a good thing for rejuvenating poor soil, but may displace some species.

In the right conditions, these shrubs form massive thickets, spreading for acres. The seeds are dispersed by birds and mammals, and the roots send up side shoots.

Use and Control

The most common control suggestion is massive amounts of herbicide, but they have deep roots and are tough to kill. Hand pulling, tilling, and mowing keeps young plants from spreading.

I think we need to take a serious look at more ways to use this plant, since it grows so well anyway. It only grows in open areas and along forest edges, so if we start taller trees where it’s growing, eventually they will shade it out. This study established native hardwood seedlings on mine tailings after cutting back the autumn olives.

Maybe we can harvest it for biomass for energy or papermaking? How about eating more of the berries, and using them for medicine? I like the suggestion of calling them “autumnberries” to give them more appeal to the general public.

The berries are high in lycopene, with 17 times more than fresh tomatoes. They’re also high in vitamins C, E, and A; phosphorous, calcium, magnesium, potassium, and iron. Traditionally, they’ve been used to treat a wide array of ailments, from irritable bowel disease to athlete’s foot to cancer.

Identification of Autumn Olives

Elaeagnus umbellata are deciduous shrubs or small trees that typically reach heights of 10 to 15 feet. Younger plants often have wicked thorns, but older plants are less thorny. They grow open spaces and disturbed areas, such as along roadsides or abandoned pastures.

The branches have long, narrow, silver-green leaves with a silvery underside, 2-3 inches (3-5cm) long. Leaves alternate up the branches, and the leaves and fine twigs are covered with silvery scales.

Autumn Olive Flowers

Yellow flowers appear in mid to late spring. They’re not very showy, but they are very fragrant. Duncan and I have cut paths through our thicket on the back hill, and it’s amazing to go under the canopy and listen to the hum of the bees in spring.

Each flower is tube shaped, about a third of an inch (8mm) long, with four petals. The immature fruit are slim and dull green.

Autumn Olive Fruit and Seeds – Both Edible

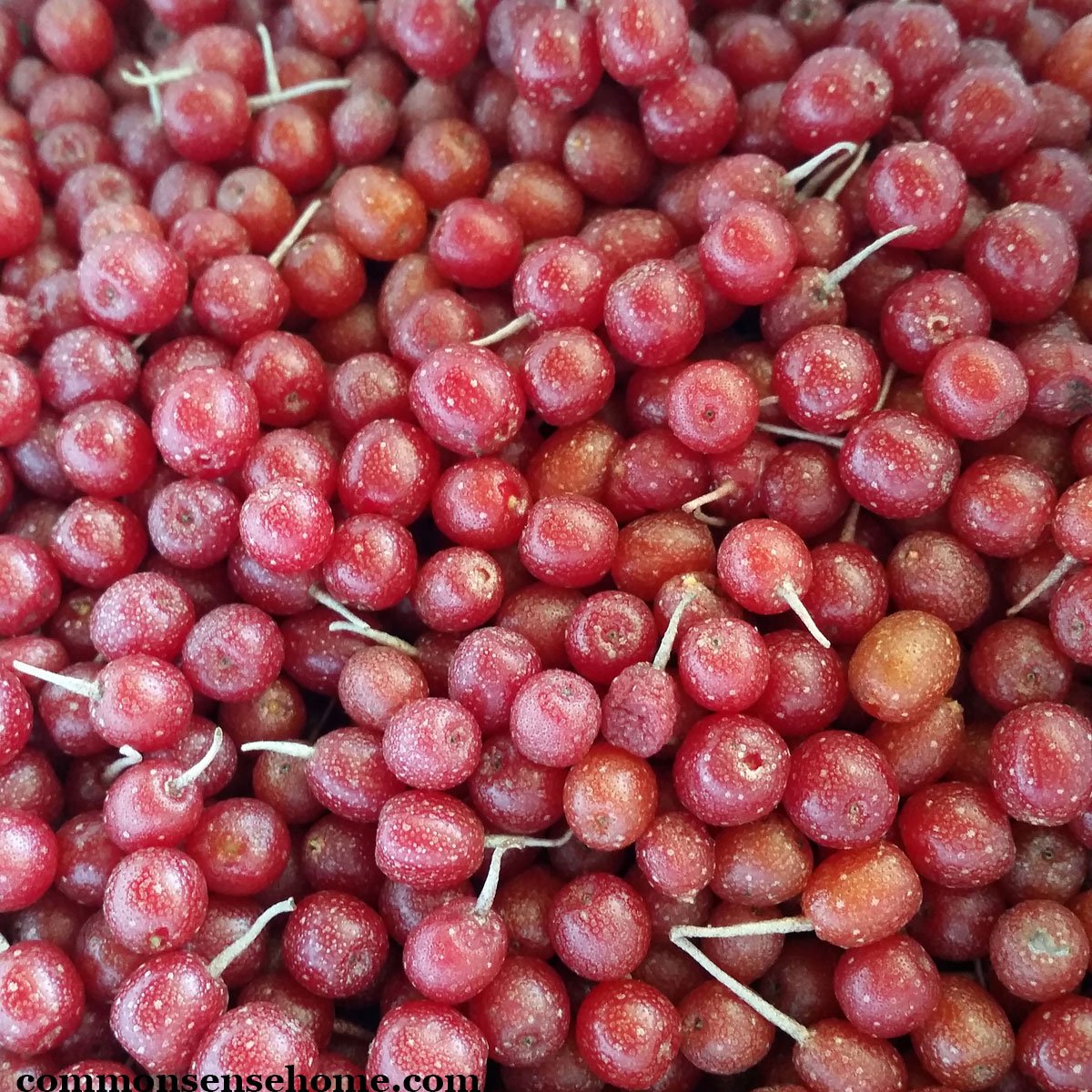

Ripe fruit are red or red-orange with silvery flecks. (The silver on the leaves and berries gives the plant one of its other common names, silverberry.) The berries are about the size of a pea, with a single large seed. The soft-shelled, oblong seeds have a point at each end.

Would you like to save this?

The berries ripen in later summer and into autumn. Make sure to test the flavor before use. Less ripe berries are astringent, riper berries are sweeter. The fruit may stay on the plant until after frost, but sometimes it ferments as it ages.

The berries and seeds are both edible, though the seeds are fairly chewy. The seed hull is comparable to sunflower hull. I advise straining out the seeds when using the berries in recipes.

Harvesting Autumn Olive Berries

Gently pluck ripe berries from the bushes. Ripe autumn olives should be red or orange-red, slightly soft to the touch, and easily come off the branches. While foraging, be mindful of the condition of the berries. Avoid berries that appear moldy, damaged, or discolored.

In some cases, you may be able to put a container below the branches and shake the berries off. Migrating flocks of birds visit our plants, so if I wait too long to harvest, most of the berries disappear.

Autumnberry Look-Alikes

Shrubs sometime confused with autumn olive include buffaloberry, Tartarian honeysuckle, yaupon holly, and Russian olive.

Buffaloberry (Shepherdia argentea) is native to the Great Plains and intermountain West. The fruit is edible and similar in color and size to autumnberries. Its leaves are blunt, and grow in pairs, and the fruit has bud stubble at the end. The fruit is edible, but bitter.

Tartarian honeysuckle (Lonicera tatarica and L. x bella) is another invasive shrub with red berries. The most notable difference is that the honeysuckle berries grow in pairs on the plant. They also lack the silvery sheen.

Yaupon holly (Ilex vomitoria) is native to coastal plain of the southeast. The toxic berries of this holly have four seeds, not one, and the plant is an evergreen, with no silver on the berries or leaves.

Russian olive (Elaeagnus angustifolia) is closely related to Autumn olive, but neither is related to true olives. E. angustifolia has narrower leaves, and grows larger than E. umbellata. Russian olive trees can reach over a foot in diameter and 35 feet tall.

Russian olive fruit is gray-green and shaped like a miniature olive. It’s abundant on the Great Plains and semi-arid regions of the West.

Autumnberry Recipes

The berries are safe to eat raw or cooked. I usually strain out the seeds before using them in recipes. While edible, they are more than I care to chew. (I don’t like sunflower hulls, either.)

I find it helpful to gently cook and mash the berries before running them through my food strainer. Sam Thayer suggest straining them raw in his book, Nature’s Garden. Either way, once strained, the pulp tends to settle, leaving a clear juice. The lycopene is concentrated in the colored pulp.

You can mix well before use, or pour off the juice and drink it separately. Either way is quite tasty. You can freeze the puree for later use.

For making fruit leather, draining off the juice speeds up the drying process. I like mix 2 cups autumn olive puree with 2 cups applesauce, to stretch my puree further. You can dry the fruit leather in a commercial dehydrator or oven. See “How to Make Homemade Fruit Leather” for more detailed instructions.

We made up a batch of autumn olive apple cider jam, and it was delicious! 3 Foragers has a recipe for autumn olive jelly.

The beautiful red color and sweet-tart flavor has inspired other recipes that typically use tomatoes, like: Autumn olive ketchup and Autumn Olive BBQ sauce. For the fermenting crowd, how about some autumn olive mead?

I hope you’ll be on the lookout for this healthy wild fruit, and give it a try. The more berries we eat, the less they can spread!

This article is written by Laurie Neverman. Laurie was raised on a small dairy farm in northwest Wisconsin, where she gathered wildflowers from the woods and pastures. Now she and her family have 35 acres in northeast Wisconsin, where they mix intentional plantings and semi-wild areas. Every season is a new opportunity to learn more about working with wild plants.

Unfortunately, even though Autumn Olive berries are edible and loved by wildlife, there are good reasons not to promote their growth and dissemination. Please read the book Bringing Nature Home by Douglas W. Tallamy, and you will see that alien species are very bad for our environment and will bring the extinction of many species of birds and the world as we know it. While these alien species give cover and food for adult birds, the leaves are not able to be eaten by insects. While this seems like it would be a great thing, it’s actually very bad. Birds need lots of insects when they are preparing to nest and their nestlings need lots of bugs after they hatch. As more and more alien species take over the landscape, the bugs will not be able to survive and will disappear. Then the birds will not be able to reproduce. Please reconsider promoting autumn olive and any other invasive species. There are many, many native shrubs that are just as good or even better than these invasives in producing berries for both human and animal consumption, and these natives are enjoyed by insects, which then gives the whole cycle of life the energy it needs.

Please consider reading articles before commenting. I’m not suggesting anyone plant more of these. I’m suggesting that the eat the fruit to help keep them from spreading.

Also, I’d suggest reading “Beyond the War on Invasive Species – A Permaculture Approach to Ecosystem Restoration“.

The earth is constantly changing. This genie is out of the bottle, so we need to learn how to manage it, because it’s not going away.

I have these as two 10-20-foot long, 5-6 feet tall hedges in my yard. I have been tempted to try the fruit and now I will. Thank you for the recipes! There was a bumper crop last year, not as plentiful this year but I’m going to try.

The flavor of the fruit varies between bushes (at least in our yard). Some are sweeter than others, but all are mildly astringent. The seeds are big in proportion to the fruit, so you have to do a fair amount of picking to get a significant harvest, but as you know, they tend to fruit abundantly. I’ve noticed that the flavor on plants varies from year to year, too, depending on conditions. We had marked certain plants as favorites because the fruit was larger and sweeter, and then the next year the same bush would be unexceptional. It’s good to check flavor each year.

What about the Russian olive; is that one edible too?

Edible, slightly sweet, more astringent. I have not had a chance to try one, but Samuel Thayer says the texture reminds him a little of dried figs.

Thanks for this very enticing introduction to Autumn berries! Most discussions I have seen emphasize the invasive issues and barely mention the tasty charms

Since the berries are produced in such abundance, and are so nutritious, I am wondering if you have seen any nutritional profiles for the seed? If the shell is so easy to break open that might make it worthwhile o collect and press the seeds for oil, or to use it as a feed additive for livestock..

No, I hunted around, but couldn’t find any good data. There was a youtube video that mentioned fats and protein, but not how much.